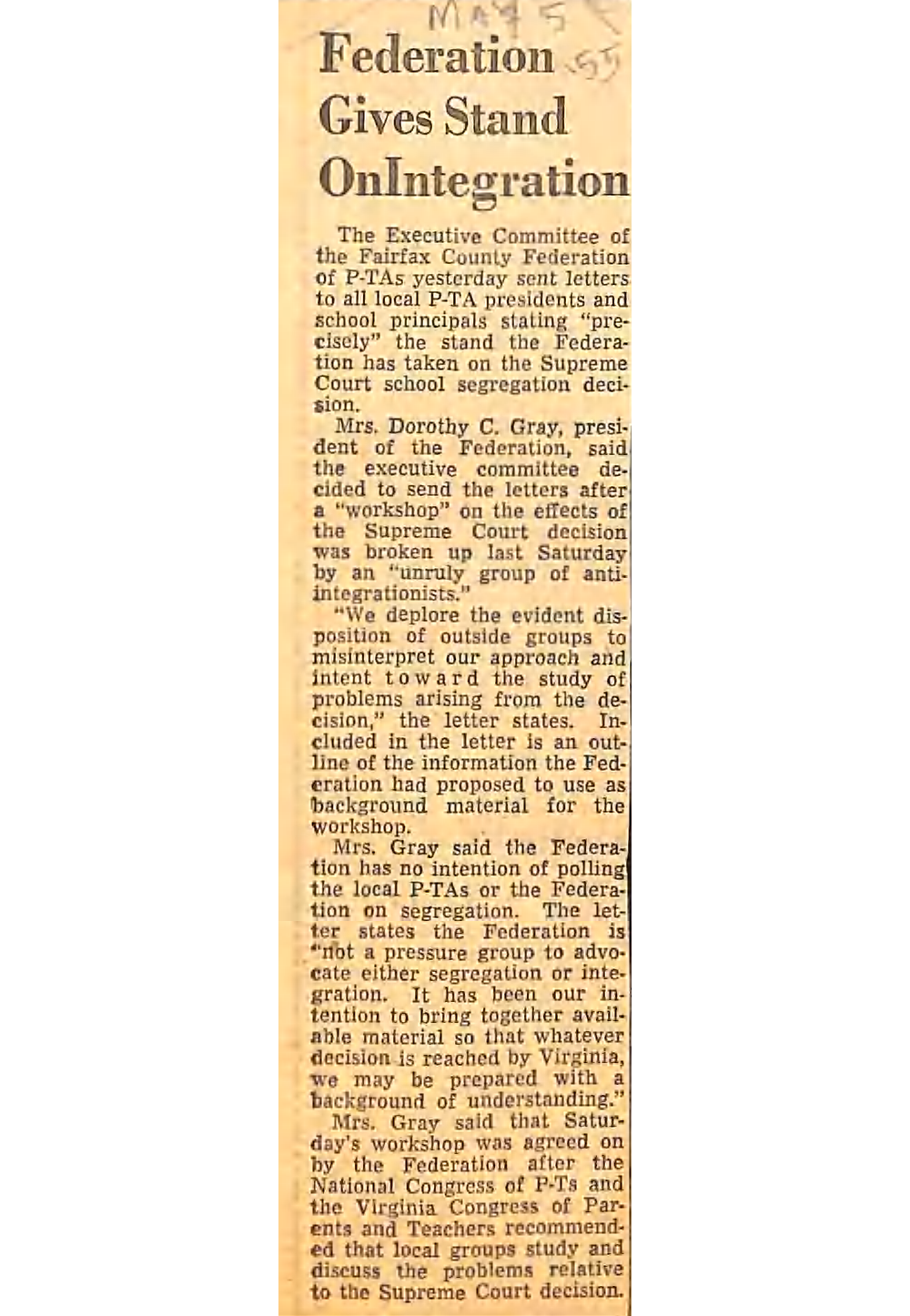

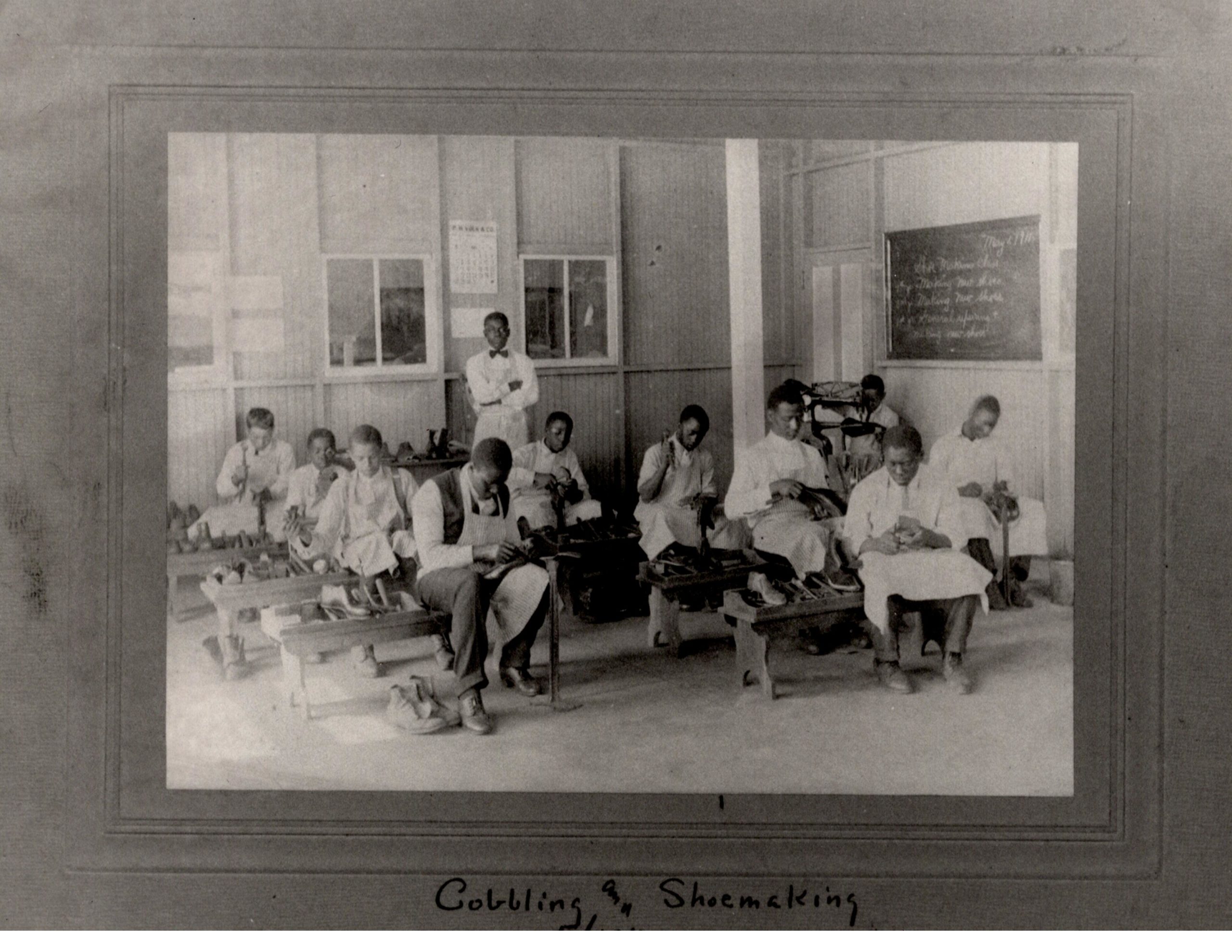

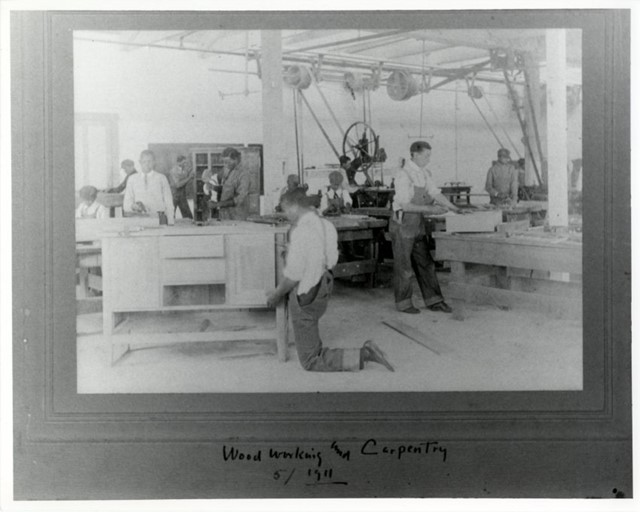

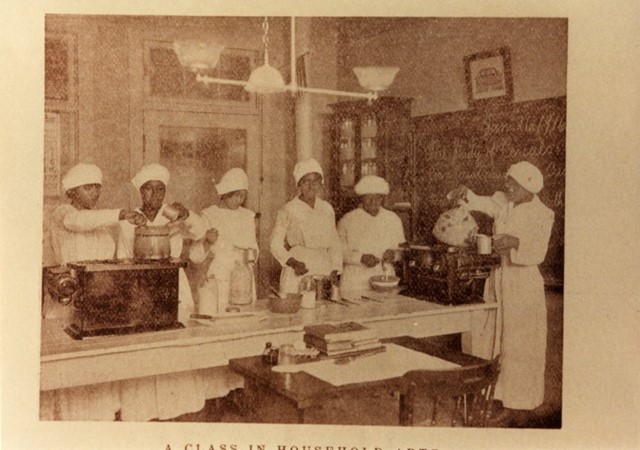

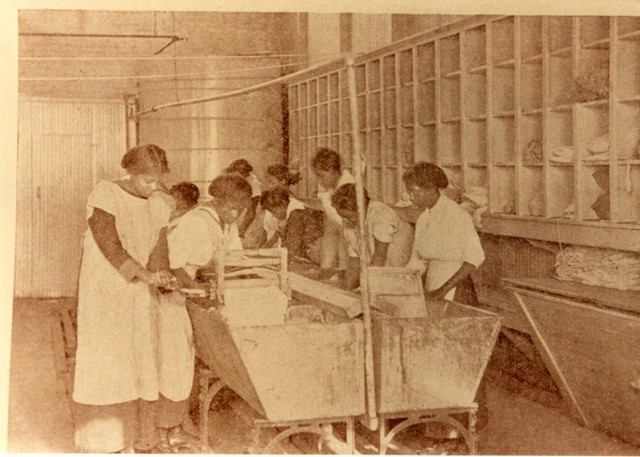

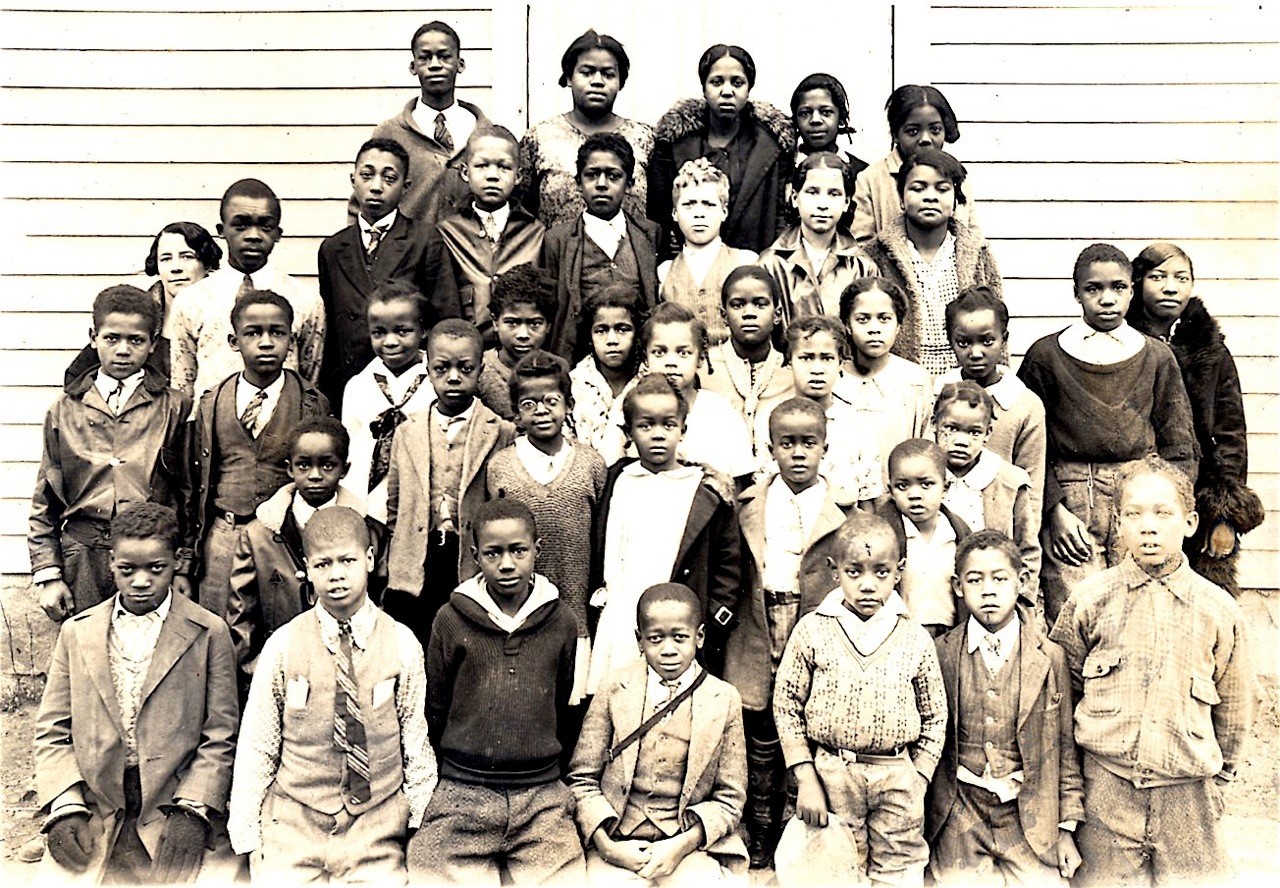

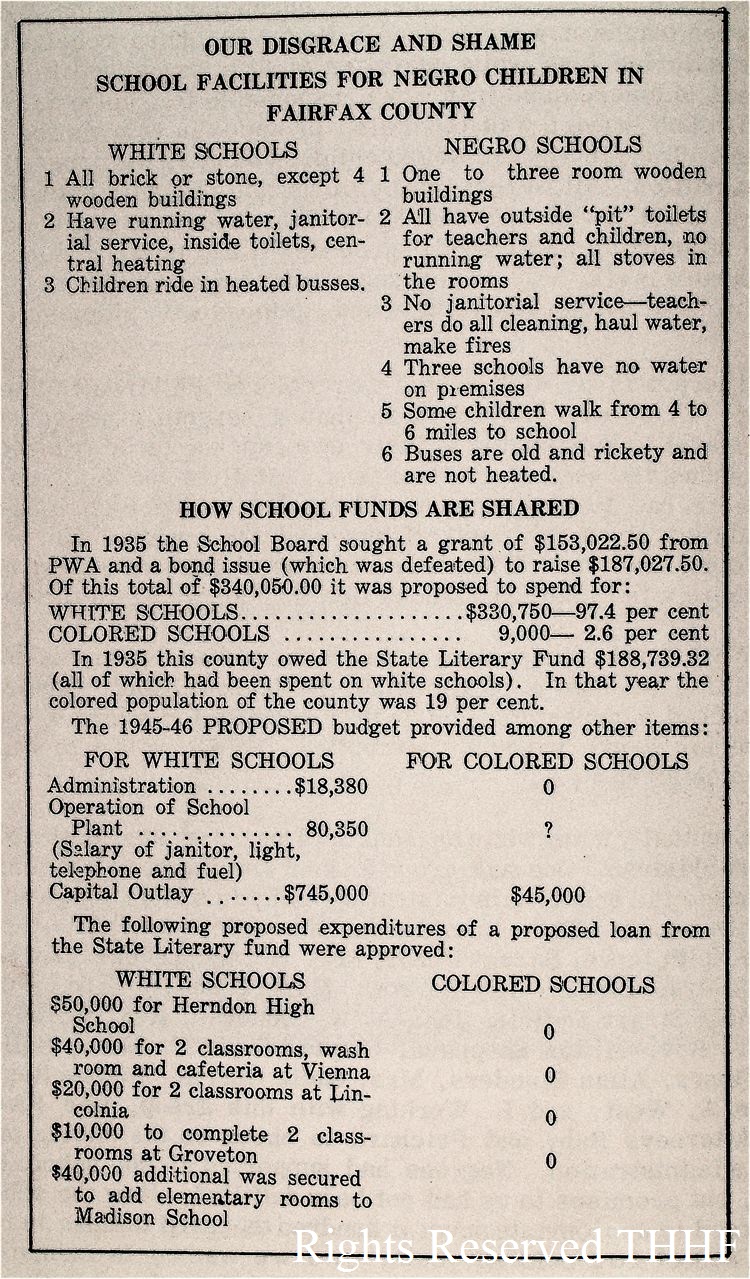

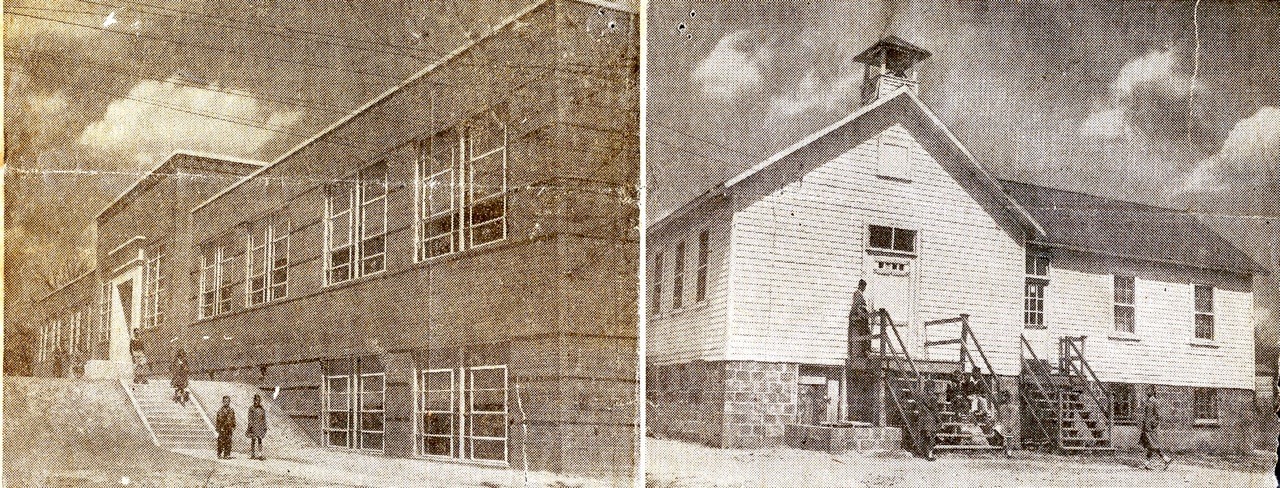

After Emancipation, freed Black families quickly established schools for Black students in Alexandria and across the region, but they received little support from local government. The 1870 law that established Virginia’s public school system required separate facilities for white and Black children, and Black schools received little funding, thereby ensuring that facilities, curriculum, teacher salaries, and educational outcomes would suffer. Schools for Black children were often one-room, overcrowded buildings that offered few grade levels, “castoff” books and furniture from white schools, outhouses, and little heat.

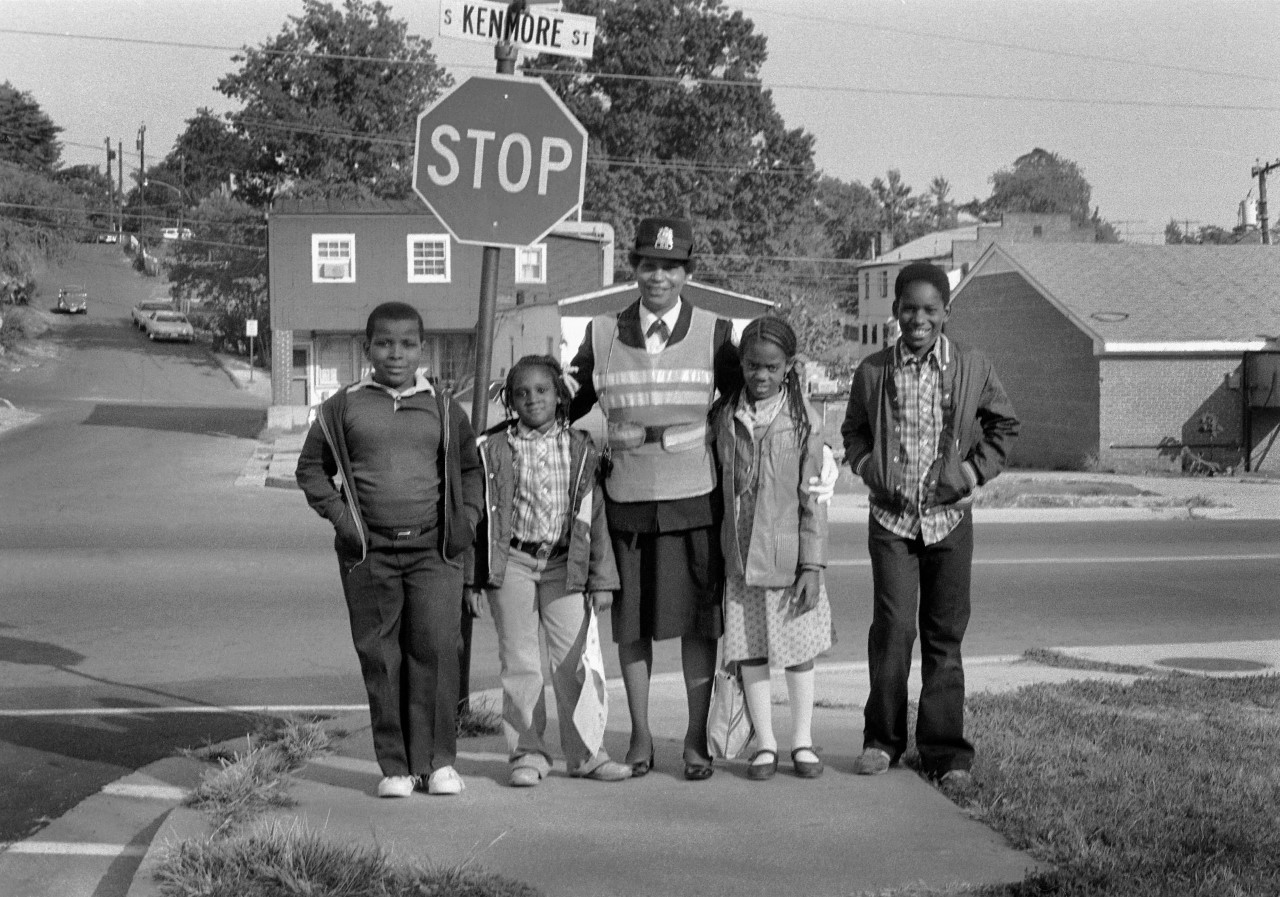

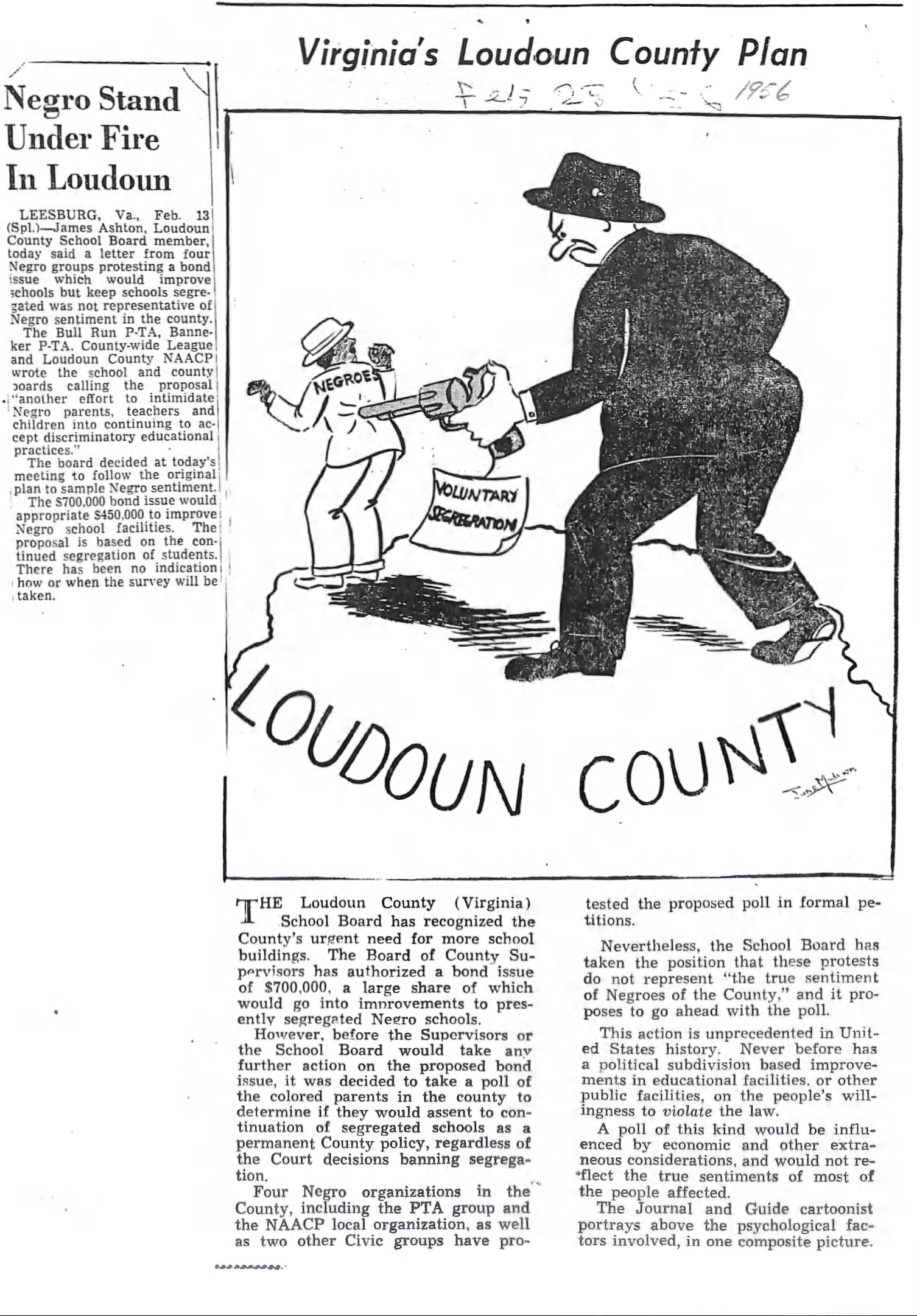

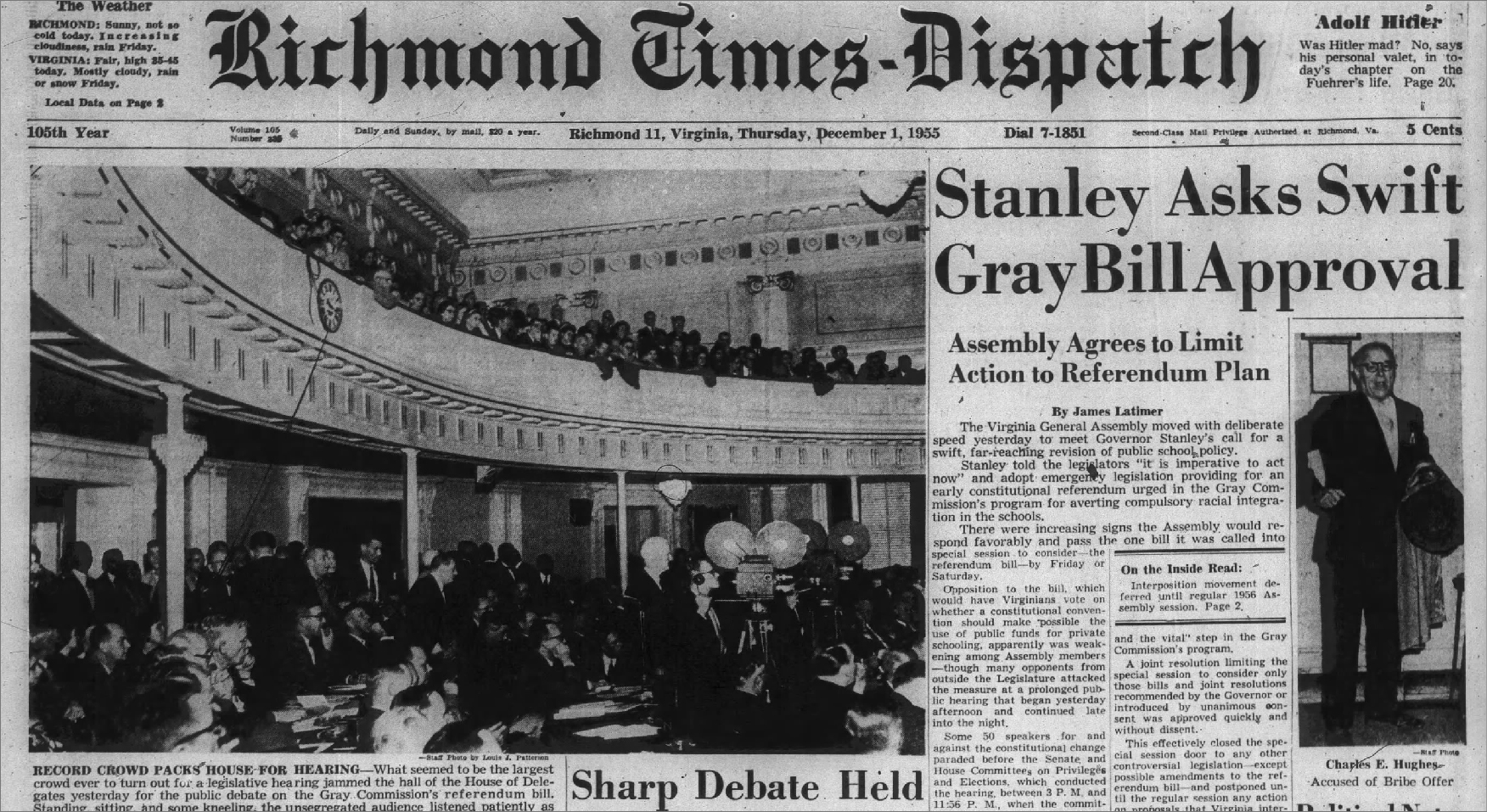

In the 1940s and 1950s, Black parents in Northern Virginia turned to the courts to demand better funding for Black schools and the right to enroll their children in white schools, but progress was slow. In 1964 the Civil Rights Act prohibited school segregation based on race, and white parents moved to outlying areas of Northern Virginia where schools had fewer minorities. This “white flight,” combined with exclusionary zoning and housing prices that kept people of color from joining them, heightened the racial segregation of neighborhoods (and classrooms). Today, many school districts are still as segregated as they were in the 1960s.

Fast Forward

A student’s zip code matters—educational resources and outcomes are connected to a child’s neighborhood, largely because schools are funded by property taxes. The disparity in local tax revenue for schools, combined with residential segregation, ensures that middle- to high-income, predominantly white school districts, which typically require fewer resources to succeed, receive more funding than schools in low-income, mostly minority neighborhoods with greater needs.

School districts in Northern Virginia should strengthen initiatives to reduce dropout rates among students of color, increase high school graduation rates, and prepare students adequately for college or vocations. State and local governments can promote policies at the school district level by working to adjust attendance boundaries to increase diversity, update funding formulas to deal adequately with fiscal needs, invest adequately in under-resourced school divisions, and expand broadband access throughout Northern Virginia. More proactive efforts are needed to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline and address racial bias in disciplinary suspensions, such as abolishing zero-tolerance policies, eliminating punishment for subjective offenses, removing police officers from schools, and implementing programs for restorative justice. An important goal that can reduce bias in disciplinary suspensions and improve educational outcomes is to increase the diversity of the teacher workforce, which in many Northern Virginia jurisdictions is overwhelmingly white. Maintaining a diverse workforce requires not only hiring more teachers of color but also enacting policies to retain them, such as easing debt burdens, changing the school culture to create a more welcoming climate for teachers (and students and families) of color, and requiring recurring cultural-competency training as part of the teacher certification process.

Stories

Dig deeper into the topics by exploring the stories of the past that have shaped the present.

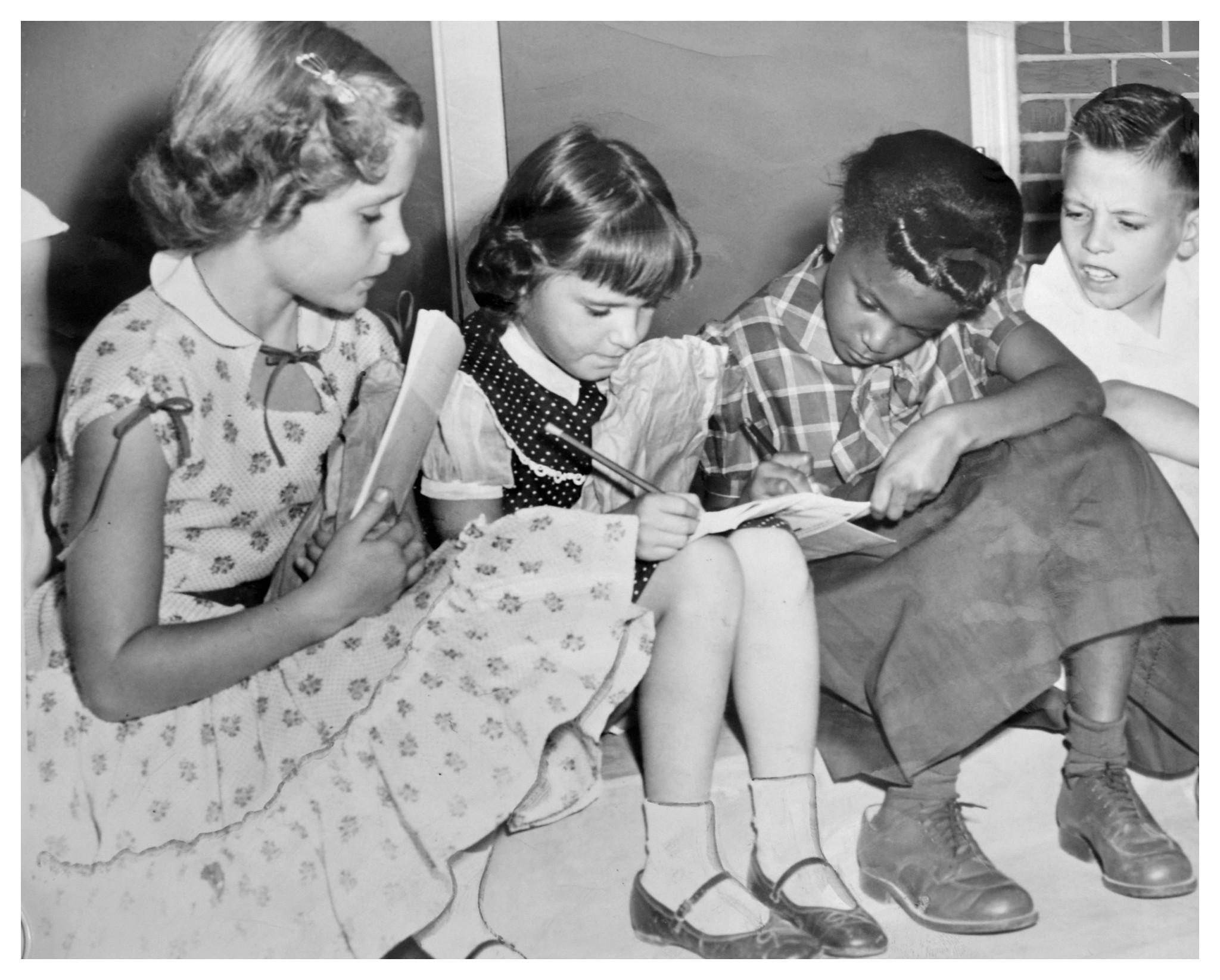

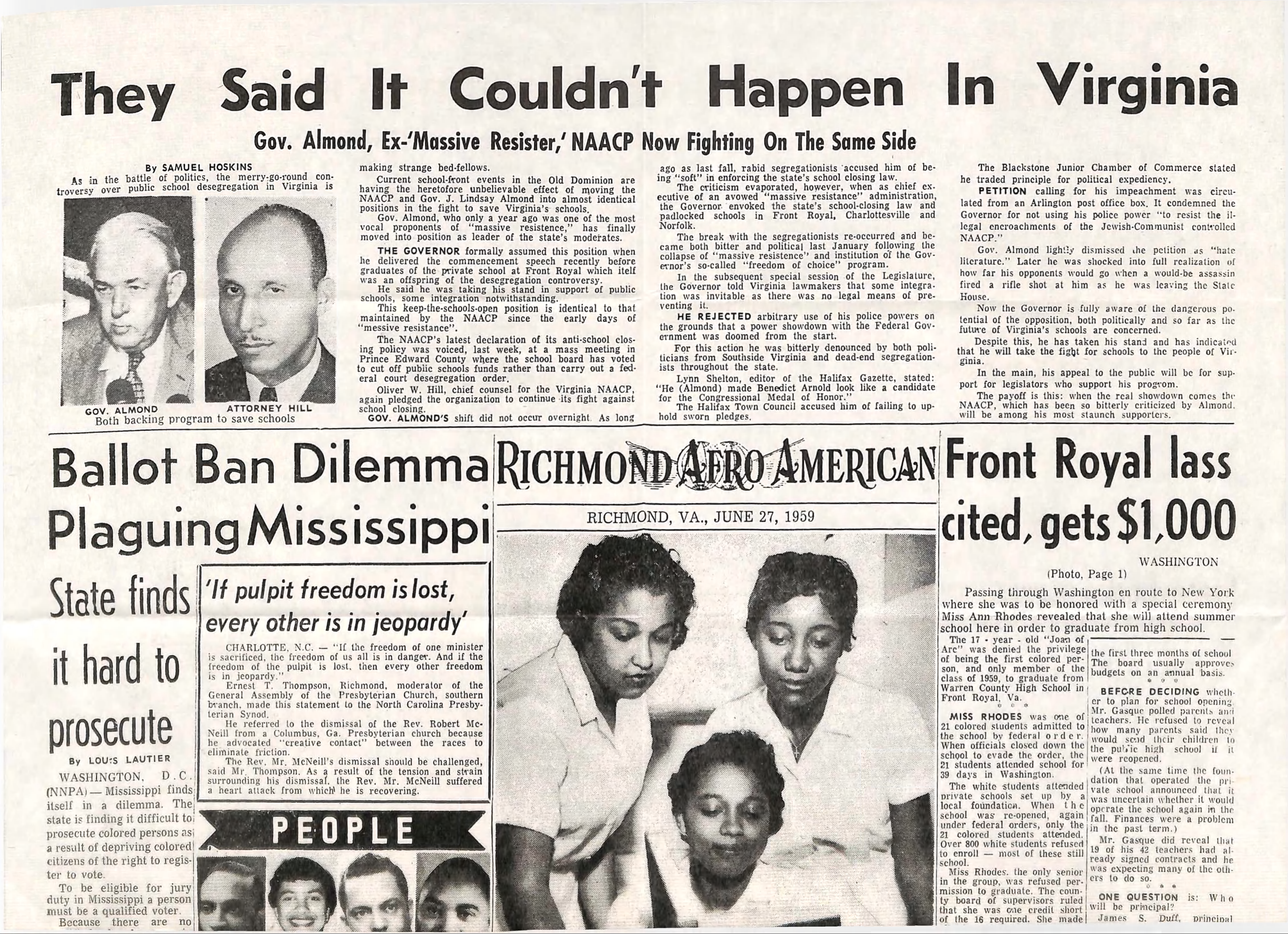

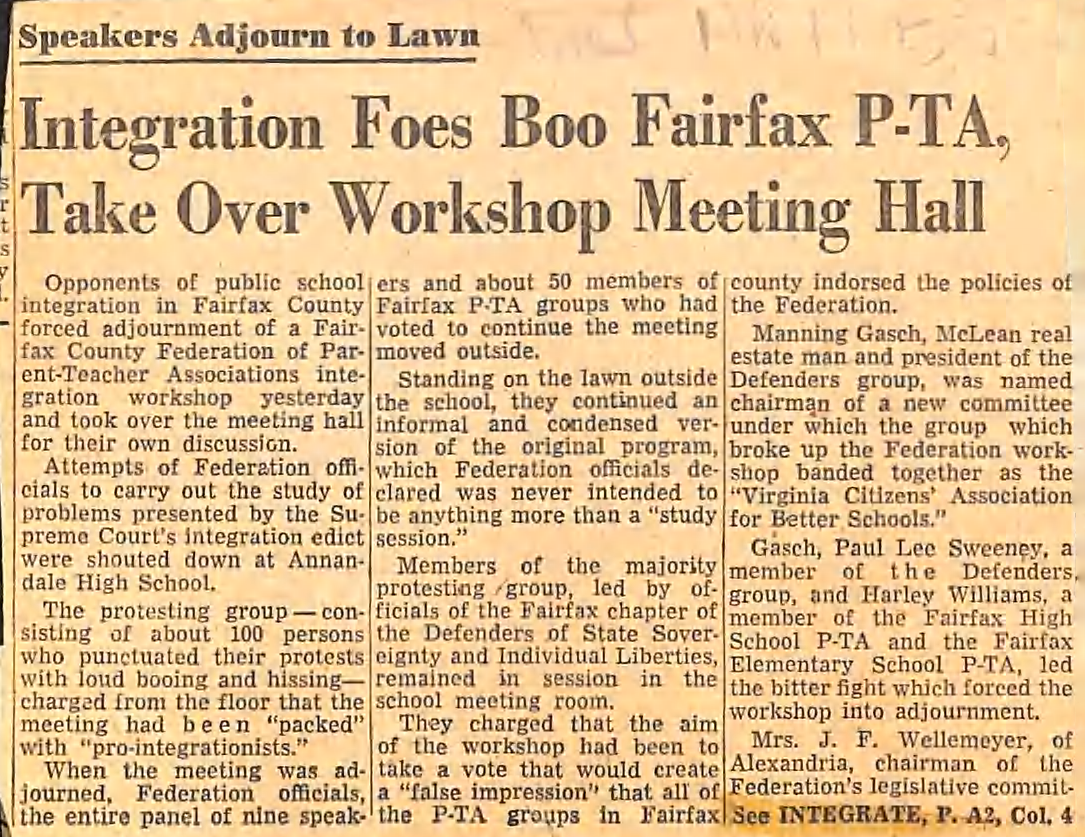

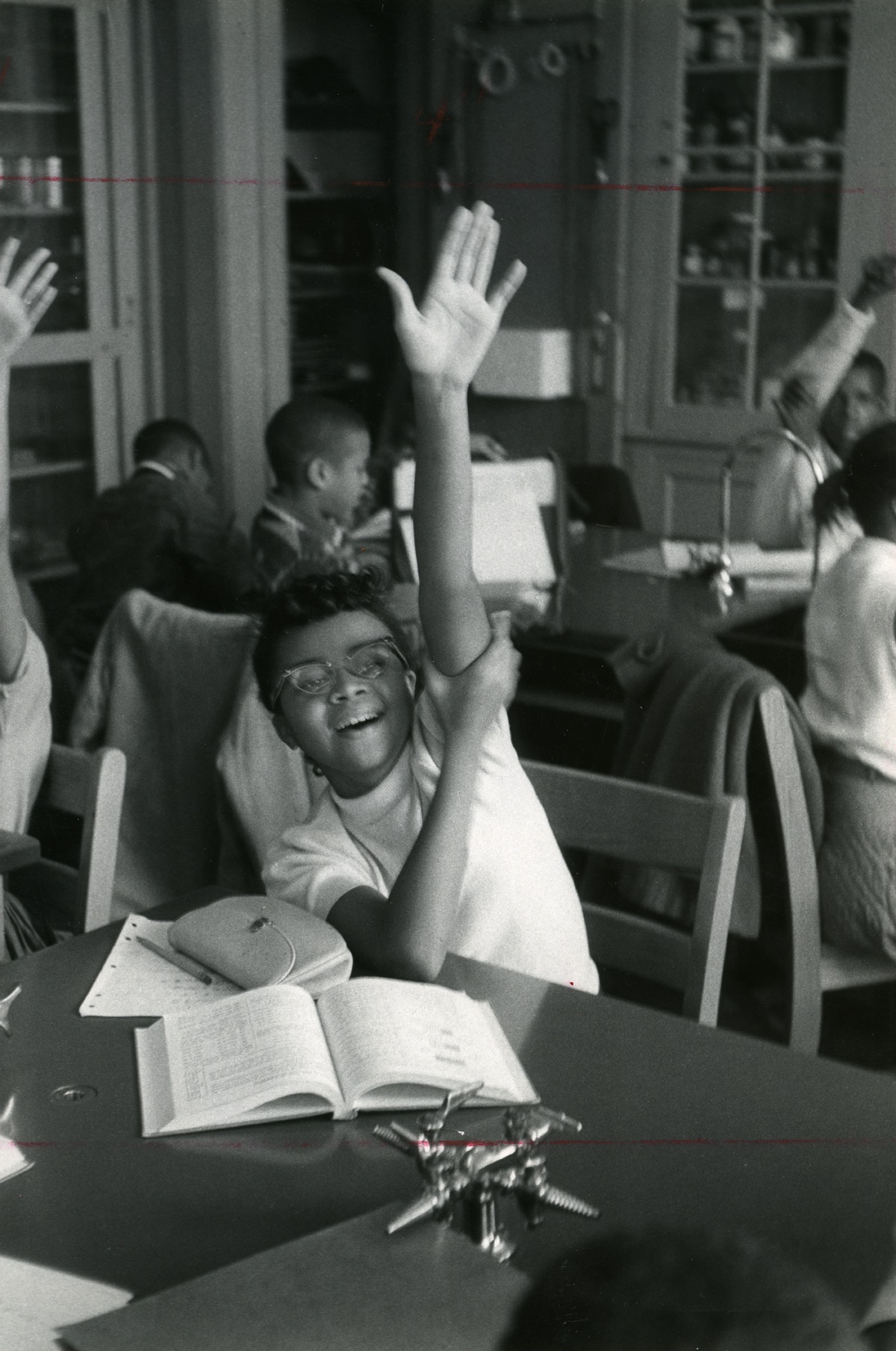

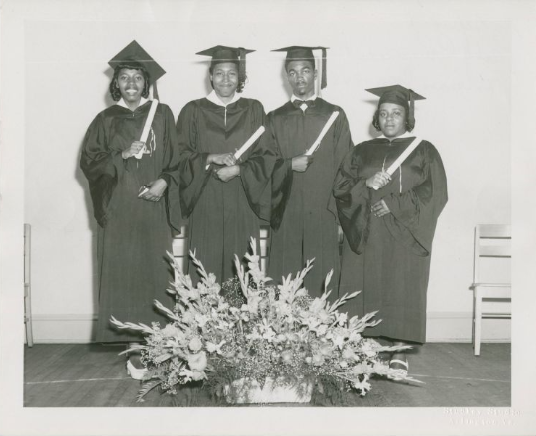

Desegregation of Stratford Junior High and the End of Virginia’s Massive Resistance

On the morning of February 2, 1959, Ronald Deskins, a 12-year old boy in Arlington, was very nervous about his first day of school. While

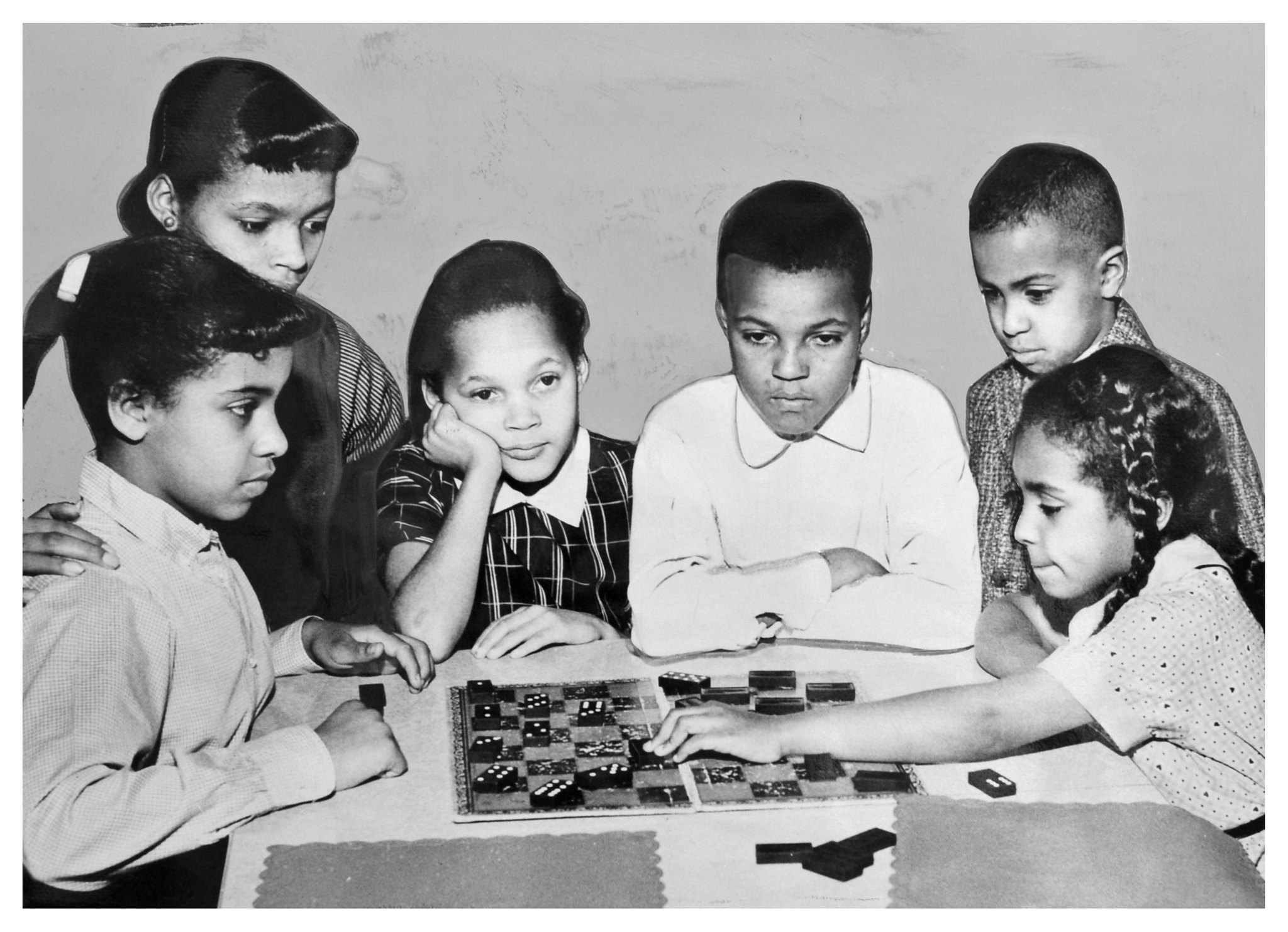

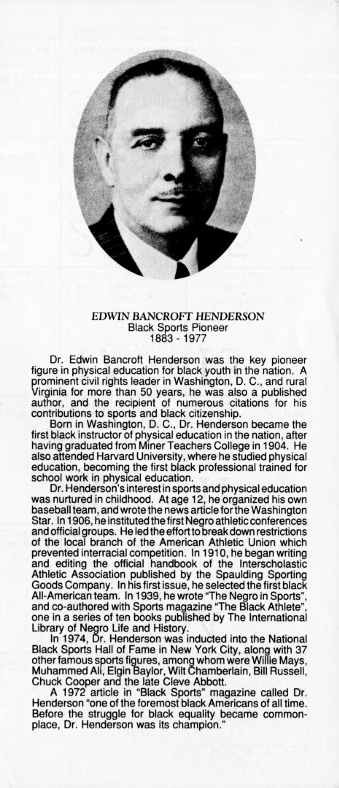

The Quest for Education

On cold winter days, Minnie Hughes, a school teacher at the Fairfax Colored School, would heatup a kettle and pour the water onto the hands