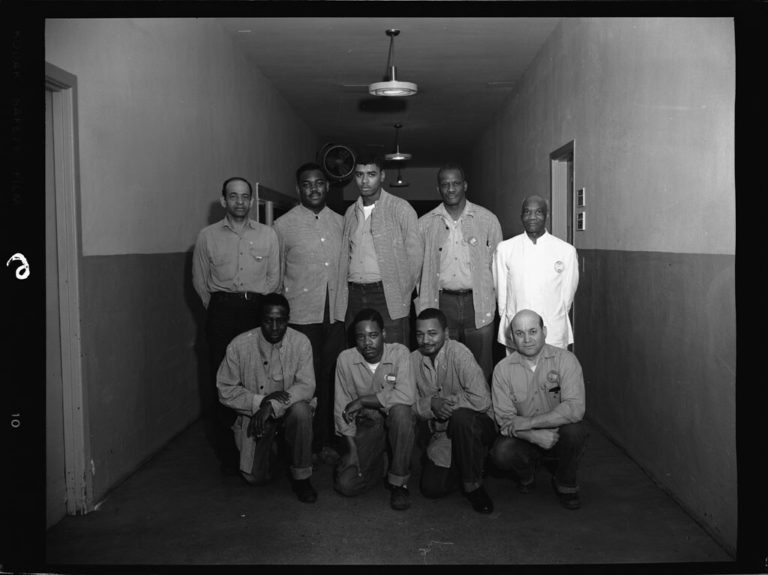

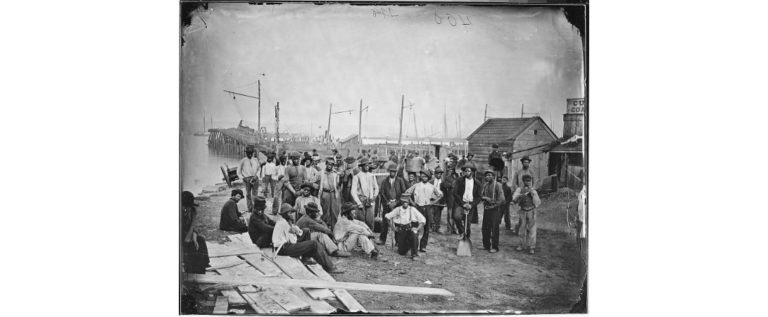

After Emancipation, freed Black people were eager to find jobs, earn money, and buy land, but—in a pattern that has lasted generations—often found themselves at the bottom of the employment ladder, confronted by a white society that resisted their upward climb. After the Civil War, most found jobs in unskilled labor or domestic work, while others used skills learned during enslavement or vocational training to work in trades. They worked at the shipyards on Alexandria’s waterfront, Arlington’s brickyards, and the dairy farms, mills, and estates in Fairfax County. Some opened their own small businesses, catering to customers who were unwelcomed in white establishments.

Unfortunately, white violence, especially in the early 1900s, destroyed many thriving Black businesses, along with whatever wealth their owners had accumulated. Many Black workers found stable employment in the federal government as clerks or in other low-level civil service jobs, but they often earned too little to accumulate wealth. In 1938, about 90% of Black federal workers in Washington, D.C. were custodians. As the late 20th century brought a shift from manufacturing to a knowledge economy, the Black population was at a distinct disadvantage because of systemic barriers to education and hiring discrimination.

Fast Forward

Even with similar resumes, studies have found that Black workers are far less likely to get called for an interview, and when hired are more likely to experience racism and wage discrimination at the workplace. Black men make 22% less than similarly qualified whites, and Black women make 12% less than white women. Black people are underrepresented in professional schools and well-paying jobs, deepening the Black-white wealth gap. Since 1970, the median income for Black households in Virginia has rarely exceeded 70% of the state average.

In addition to efforts to improve educational attainment among youth, vocational training programs are needed to help workers transition to 21st-century jobs. A study that was conducted for Fairfax County included a number of recommendations for creating pathways to such jobs. Employers in Northern Virginia can also reduce job inequities by observing equal opportunity regulations to eliminate racial bias in hiring and promotions and by offering workers a wage that keeps pace with the region’s high cost of living, adequate and affordable health insurance, and employer-sponsored retirement programs. Policies to address the loss of such benefits in the gig economy are increasingly important.

Stories

Dig deeper into the topics by exploring the stories of the past that have shaped the present.

A Head Start: How Generational Wealth Helped Some Get Ahead

Northern Virginia is known for its affluence. Loudoun County, for example, currently boasts the highest median household income of any county in the United States.

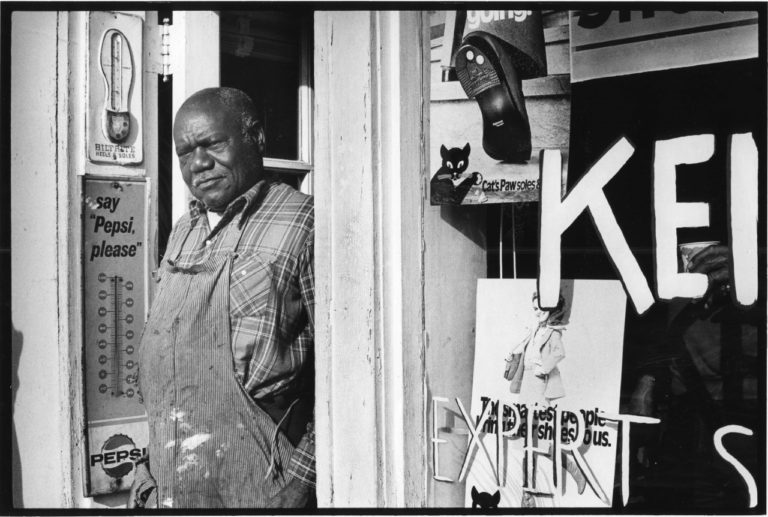

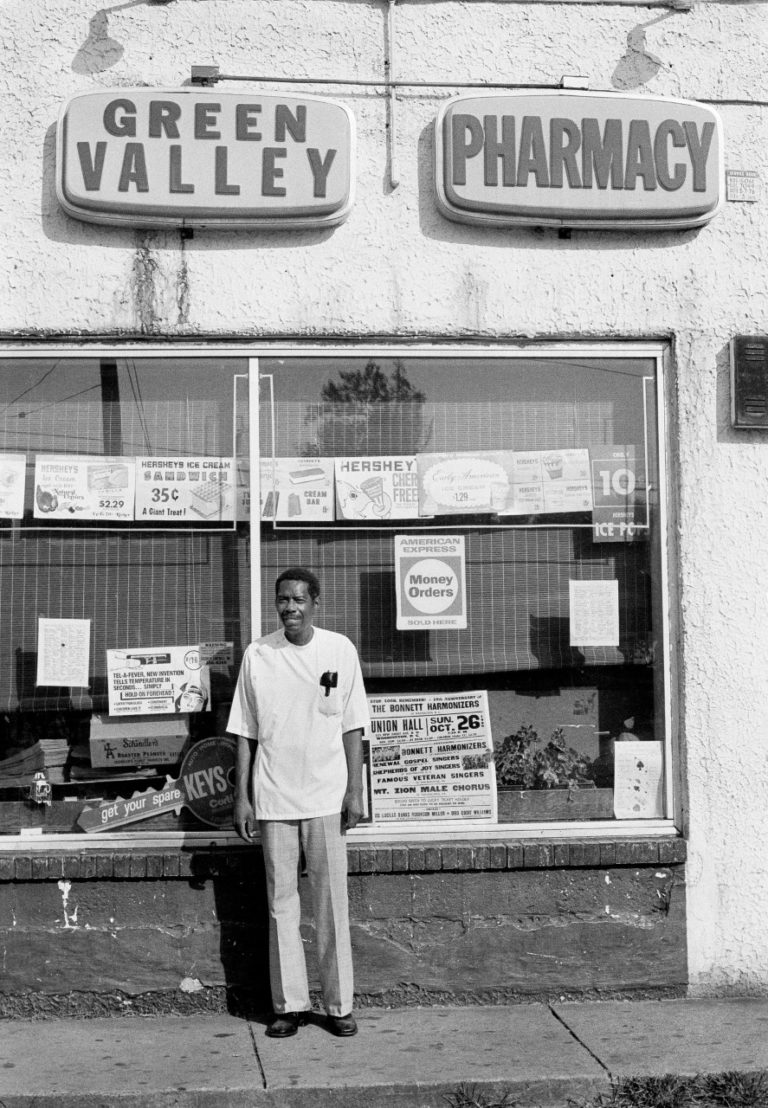

Black-Owned Businesses: Serving Their Neighbors, Who Were Unwelcomed Elsewhere

When Leonard Muse (1923-2017) was young, a neighbor asked him to go to the pharmacy to fill a prescription. When he arrived, he was tired