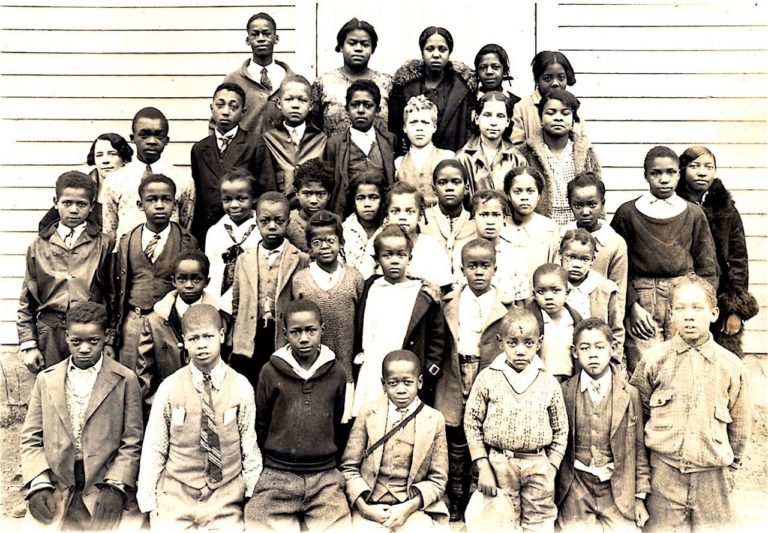

On cold winter days, Minnie Hughes, a school teacher at the Fairfax Colored School, would heatup a kettle and pour the water onto the hands of her students to keep them warm. For teachers of color in the early 1900s, there was more to being a teacher than just teaching. Hughes, who lived on a small farm on Braddock Road, drove herhorse and buggy for three miles to reach the school each day. The school relied ona pot-bellied stove for heat, had no electricity or indoor plumbing, and had an outhouse for sanitation. Hughest counted on the older children to help with general chores and cleaning.

Even as late as1945, a study found that Arlington County’s 15 Black schools had no running water or modern toilet facilities, and two had no electricity. Black schools were underfunded and less well off than white schools. Black teachers were paid far less than their white peers; Hughes received no regular pay until 1916, and then received only $8 per month.

But Hughes recalled in interviews that the community’s help kept the school running.

“Mostly, however, I remember the students and their parents. I shall always treasure the support and helpfulness of the parents and interested citizens. Many of them gave greatly of themselves. I have delighted in seeing my former students. I have taught parents and their children.” Hughes retired in 1937. When she was interviewed at the age of 98, she was only two years younger than Fairfax County Public Schools.

The Creation of Black Schools

The desire and struggle for education have been a persistent theme throughout Black history in the United States. But white people, out of fear of the power and knowledge that Black people could obtain through education, opposed and organized against their efforts from colonial times to the modern era.

There were few Black schools before the Civil War. In 1832, in the wake of the Nat Turner rebellion that alarmed the white population, the Virginia legislature banned the education of Black people, both enslaved and free. Although the law spared Alexandria (which was then part of Washington, D.C.) even that city’s Black schools were forced to close in 1846 when it became part of Virginia.

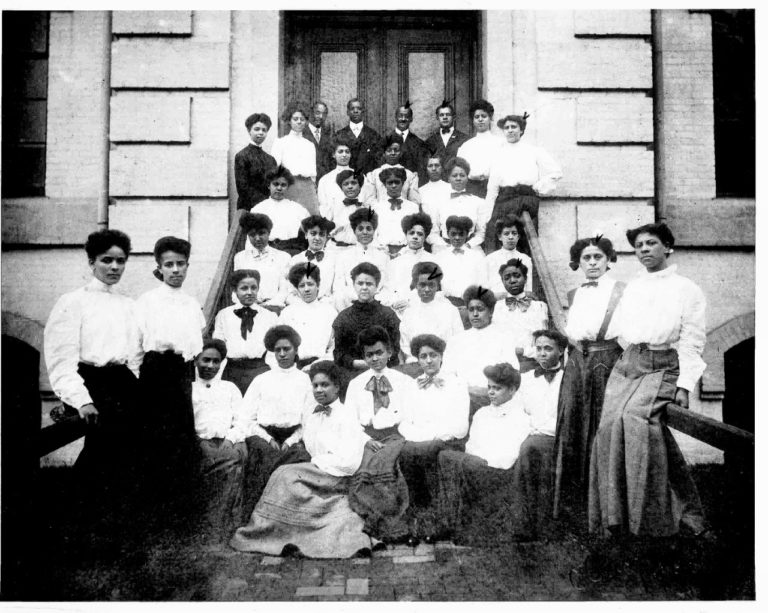

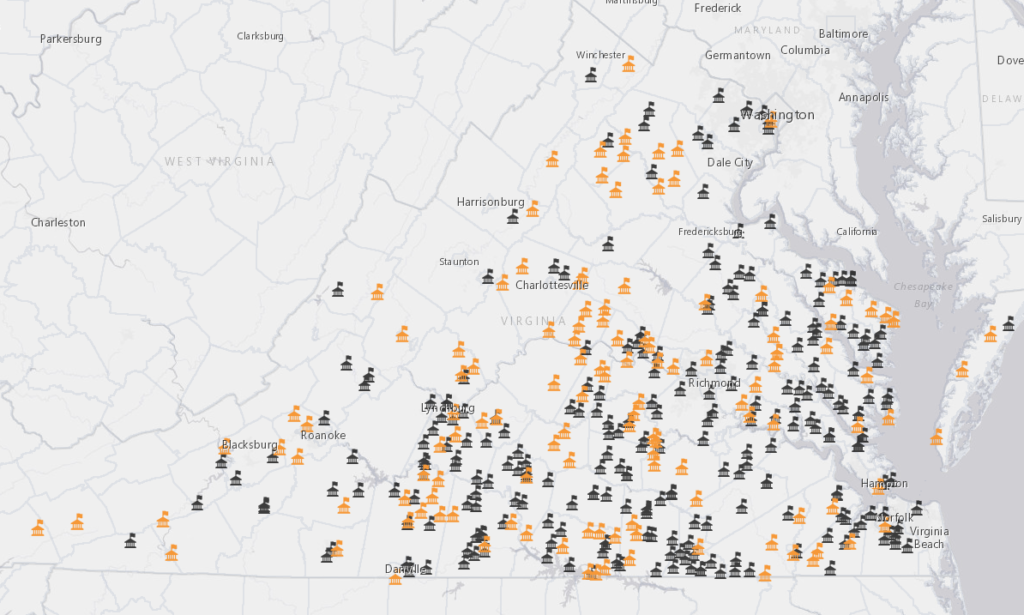

When the Union Army occupied Alexandria early in the Civil War, the Black community began opening schools at remarkable speed, led by women such as Anna Bell Davis, Mary Chase, Jane Crouch, and Harriet Jacobs. These schools included the Columbia Street School and Saint Rose Institute opened in 1861; the First Select Colored School, Beulah Normal and Theological Institute, and Leland Warring school in 1862; the Union Town School, Sickles Barracks School, and Newtown School in 1863; and the Jacobs Free School in 1864. Schools for Black children opened elsewhere in Northern Virginia, including the Freedman’s Village school (1863), Falls Church Colored School (1864), a school at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Gum Springs (1865), Snowden School, Mount Pleasant school in Alexandria (1867), Vienna Colored School (1867), Frying Pan School in Herndon (1868), and Jefferson School in Arlington (1870).

In the early 1900s the Fairfax Colored School League was active in raising funds and petitioning the school board for newer buildings. Additional help came from philanthropists. For example, Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck & Company, and a friend of Booker T. Washington, established the Rosenwald Fund, which built or updated schools for Black children. Between its founding in 1917 and 1932, the fund built more than 5,000 “Rosenwald schools” in 15 southern states, including more than 350 in Virginia (with four in Fairfax County alone).

The Black community turned to the courts in the 1940s, suing for better funding of Black schools and the right to enroll children in white schools. The NAACP aided this effort, viewing Northern Virginia as an ideal setting to challenge school segregation. In 1950, in a case involving the all-Black Hoffman-Boston school (Carter v. School Board of Arlington County), a federal court ordered the school board to provide “equal facilities” at Black schools.

But progress was slow. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional in the 1954 decision Brown v. Board of Education, Virginia launched the “Massive Resistance” movement, shutting down schools that faced a desegregation order.

Secondary Education: The Manassas Industrial School

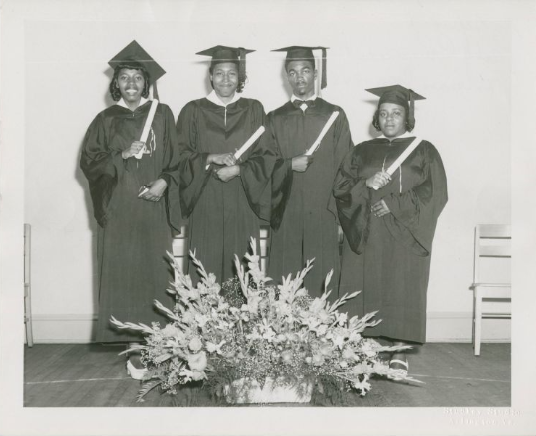

Black students had even more limited access to secondary school. In the late 1800s, those who wanted additional education, and could afford the trolley or bus fare, could travel to Washington, D.C. where high schools for Black students existed. Some traveled to the Manassas Industrial School, an institution for Black students founded in 1893 by formerly enslaved Jennie Dean.

Dean wanted to empower young people through education. The Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth was founded with the mission to provide vocational training to the Black community. However, much of its focus was on academic study, rather than simply training students in the trades.

Dean founded the school through intensive fundraising efforts. In 1892, she organized a massive picnic dinner and raised seventy-five dollars selling foods that were priced at ten to fifty cents. Eventually, $1400 wereraised to purchase land for the school. She then obtained funds from Emily Howland, a wealthy New Yorker active in women’s suffrage, and named the first school building Howland Hall.

The school was dedicated on September 3, 1894. Six students enrolled in October, but within months the school had 75 students. They learned skilled trades, along with English, spelling, and arithmetic. men learned blacksmithing, carpentry, and shoemaking, and women learned cooking, canning, and sewing.

Educational trail blazers like Jeenie Dean and Minnie Hughes – as well as others like Anna Bell Davis, Mary Chase, Jane Crouch, and Harriet Jacobs – dedicated their lives to educating Black youth and helping them pursuebetter lives, a goal that their successors pursued in Northern Virginia throughout the 20th century. That quest continues today, when the knowledge economy makes education vital to economic mobilityand better life outcomes. Educational outcomes are less favorable for Black and brown students, in Northern Virginia and many other parts of the country, and the struggle for equity and quality education continues.

References and Recommended Reading

Peake, Laura Ann, “The Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth, 1894-1916” (1995). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. William & Mary.

Rita G. Koman, Legacy for Learning: Jennie Dean and the Manassas Industrial School, OAH Magazine of History, Volume 7, Issue 4, Summer 1993.

Johnson, William Page. “African American Education in the Town/City of Fairfax.” The Fare Facs Gazette, 2006.

Oberle, George D. “Manassas Industrial School” George Mason University.