Eminent Domain and the Displacement of Black Communities

More than a century ago, before there was today’s Prince William Forest Park, there was a community of miners collectively known as the Cabin Branch Community. Founded after the Civil War by free Black people, the community included the two towns of Hickory Ridge and Batestown. While hundreds of small-scale farmers, laborers, and others lived in the area, most residents were employed by the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine, which operated from 1889-1920.

During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which, along with other work programs, created many jobs and helped create and maintain conservation areas. In the 1930s, despite having been home to about 150 families, the federal government purchased the land through eminent domain to create Chopawamsic Recreational Development Area, later known as Prince William Forest Park. Ending a 400-year history of the community in the area.

“For The Good of the Public”

“...nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Eminent Domain is the power of the government to take private property and convert it to public use. The Fifth Amendment of the constitution provides that the government must provide “just compensation” to the property owners. However, “just compensation” may not always be fair and the government is notorious for paying property owners less than market value for their properties. Listen to what Historian Nancy Perry says about the use of eminent domain in East Arlington.

World War II expanded the size of the Federal government, increasing demand for land in Northern Virginia to build military installations and to house (largely white) incoming workers while setting the stage for Black residents to lose their property. Citing eminent domain, the government forced Black landowners in Alexandria and Arlington to sell. Large apartment communities were built for white defense workers, such as Fairlington Village (reportedly the largest apartment complex in the country) and Chinquapin Village in Alexandria. A private company built Parkfairfax, where a restrictive covenant barred Black residents—and where Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford later lived as members of Congress. After renting at Parkfairfax, Congressman Ford bought a home in Chinquapin Village, where he was living when, as Vice President, Richard Nixon’s resignation elevated him to President.

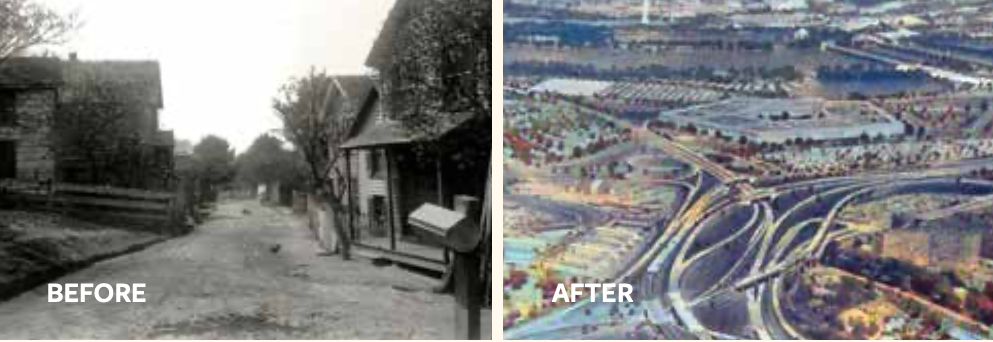

Eminent domain displaced historic Black communities, Notably, in February of 1942, in order to build the Pentagon and its surrounding roads, the federal government condemned East Arlington, giving the residents less than a month to evacuate. Queen City, another nearby Black community, was razed at the same time to free up land next to the Pentagon for a cloverleaf to help commuters access nearby Washington Boulevard and Columbia Pike. The 9/11 memorial marking the spot where American Airlines Flight 77 struck the Pentagon is built on the land once occupied by Queen City. During World War II, housing surrounding the nation’s capital was in short supply. Some Black residents who were displaced by the construction were able to find homes in nearby communities, but most were left with few options.

Displaced families were moved into trailer camps and, having garnered the sympathy of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, moved again to newly constructed, racially segregated public housing projects, such as the George Parker (later Ramsey) Homes and James Bland homes in Alexandria. As overcrowding worsened, War Housing Centers asked Black families to see if they “can ‘double up’ a bit.” No white people lived in the trailer camps, and affordable housing was prioritized for white people; as of 1944, the public had financed almost 3500 permanent housing units, but only 100 public housing units for Black people.

Examples of eminent domain can still be found today and are not uncommon. In 2017, a small enclave of descendants of Livinia Blackburn Johnson, a freed slave, living along Carver Road in Prince William County, was threatened by plans for a 38-acre computer data center. The state had invoked eminent domain to authorize Dominion Virginia Power to seize the land, the same land that the Johnson heirs had occupied for over 100 years. The plan was eventually abandoned as county officials were reluctant to grant easements needed for the project.

Priced Out: Affordable Housing

The expanding interstate highway system in Northern Virginia in the 1950s created corridors of low-priced property along the highways, an area that local governments zoned for high-density, mixed-use housing. Although the tower and garden apartments along Shirley Memorial Highway were first occupied mainly by white residents, the “white flight” to more distant suburbs that began in the 1960s led to disinvestment and declining property values in places like the Beauregard and Shirley-Duke areas of Alexandria, which were increasingly represented by people of color. Housing prices skyrocketed, the area’s supply of affordable housing failed to keep pace with needs, and many people of color wanting to buy homes were forced to look elsewhere. Many gravitated to no-frills housing that developers like Don Hylton were building in new subdivisions along I-95 in Prince William County.

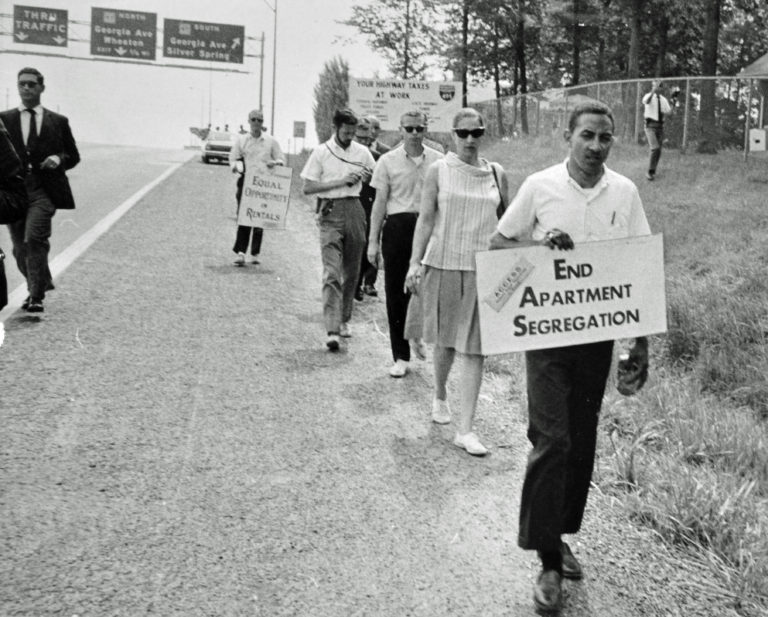

In October 1966, in an effort to garner public attention about the lack of housing that was affordable, hundreds of protesters marched along the I-495 Beltway and other major thoroughfares and through segregated neighborhoods, holding sit-ins and picketing private apartment developments to demand “Equal Opportunity Rentals.” Facing spiraling property values in Fairfax County, many people of color chose to settle in Woodbridge, Dale City, Dumfries, and new subdivisions in Prince William County, commuting further to work in order to own property. Under the headline “Fairfax growing Whiter,” a 1970 Washington Post article noted that 6.6% of the county’s employees were Black but with “many of them are living in neighboring Prince William County, where cheaper housing is available.”

The current location of Black property owners in Northern Virginia, disparities in their property values, and the large population that cannot own property or transfer wealth to their children are a product of historical forces, among them the use of eminent domain to uproot Black families from land and homes that some had owned for generations. Institutional racism in the form of exclusionary housing policies separated Blacks from their property, limited access to capital and lending, reduced lifetime earnings, concentrated wealth in largely white communities, and banned people of color from moving to their neighborhoods. Although past practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants were ultimately deemed unconstitutional and banned under the Fair Housing Act of 1968, housing prices in Northern Virginia remain out of reach for much of the population. And economic forces continue to limit access to property and segregate people of color within the dwindling number of communities they can afford.