Table of Contents

Introduction

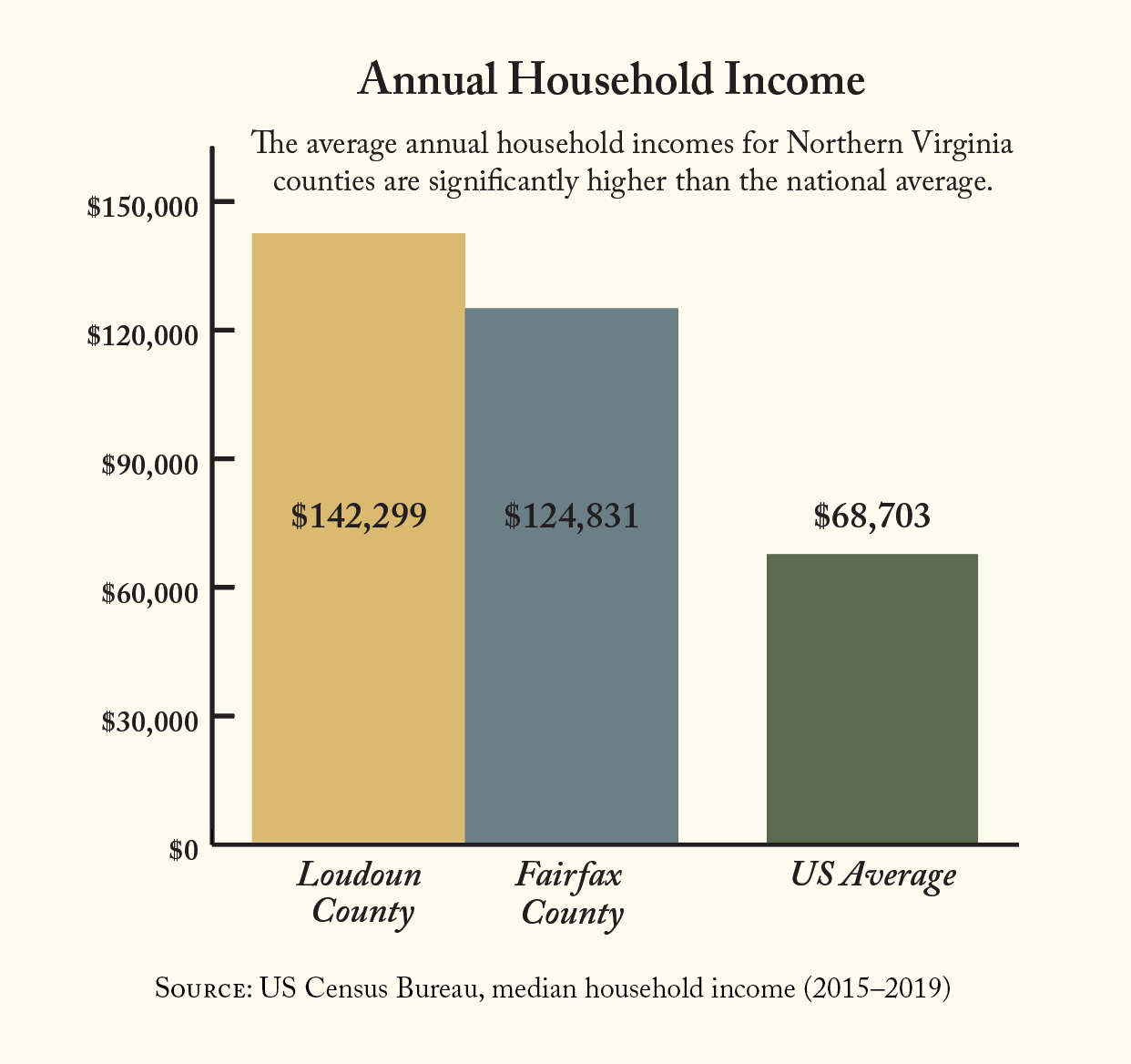

The Northern Virginia1 suburbs of Washington, DC are among the wealthiest in the nation. For example, annual household income in Loudoun County and Fairfax County averages $142,299 and $124,831, respectively, well above the U.S. average ($68,703). But the region’s prestige and affluence mask deep inequities.

Pockets of extreme disadvantage exist amid the wealth. In 2017, the Northern Virginia Health Foundation commissioned a study by the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, which documented a 17-year gap in life expectancy across Northern Virginia. It identified 15 “islands of disadvantage,” clusters of census tracts where residents — disproportionately people of color — face austere living conditions that take years off their lives.

Many “islands of disadvantage” have struggled for decades, while other communities thrived, fueling a false narrative that the residents themselves are responsible for their plight. However, a closer look at history paints a different picture. The boundaries of these neighborhoods, along with their demographic composition and economic status, are products of policies that choked off resources to communities, creating an inevitable downward spiral. Policies of exclusion and segregation had the combined effect of preventing people of color from finding better lives elsewhere and facilitating the disproportionate concentration of wealth in white communities.

This report recounts that history, not only to revisit a distant past that today’s Northern Virginians may not recall but also to explain why current conditions exist. Recalling how past policies have shaped the present reminds us that changing today’s policies can improve the future. The central thread of this history is racism — interpersonal and structural — and the consequences of practices that embrace a “hierarchy of human value.” This report chronicles African American (hereafter referred to as “Black”) experiences in Northern Virginia over the past 400 years.

Colonialism: The Birth of Systemic Privilege

The affluence of Northern Virginia can be traced to 1649, when King Charles II of England rewarded his supporters with large land grants across the region, seized from the Indigenous peoples who had lived there for centuries. These British landowners, who were wealthy upon arrival to the colony or made their fortune through land acquisition, had surnames like Fairfax, Culpeper, Lee, Washington, and Mason. The wealth they accumulated and passed to their heirs relied on the forced labor of enslaved Africans. Enslavement also enabled these white landowners to amass political power, becoming members of the House of Burgesses, governors, and Founding Fathers.

Historical figures from Northern Virginia who signed the Declaration of Independence (Francis Lightfoot Lee and Richard Henry Lee), led the Revolutionary War (George Washington), and drafted the Virginia Constitution (George Mason IV) were all men who enslaved people, and so were their ancestors. Four generations of the Lee family enslaved Black men, women, and children before Confederate General Robert E. Lee was even born.

In time, tobacco plantations gave way to wheat and dairy farms and then to suburban development and the posh homes of Northern Virginia’s social elite. Here lived not only local politicians but also U.S. Senators, generals, and cabinet secretaries. Over generations, white people went to lengths to secure their advantages: they adopted systems, institutional structures, and policies that helped them grow their wealth, retain power, cloister themselves in white communities, and keep people of color from entering their neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces.

Systems of exclusion and discrimination pushed Indigenous and Black people out of places that were their homes for generations. These efforts erected the architecture of systemic privilege — opening doors of opportunity for some people to pursue education, careers, and more prosperous lives, while closing the doors for others. Policies of exclusion and systemic racism inflicted damage that has cascaded across generations, literally drawing the map of where Black people and neighborhoods of concentrated poverty are found today.

As is true today, social standing and political power in the colonies revolved around individual wealth. Much of the land in Northern Virginia was obtained by Thomas Culpeper (1635–1689,) governor of Virginia, and inherited by his grandson, Thomas Fairfax (1693–1781). Fairfax, living in England, appointed land agents to manage his property, such as Robert “King” Carter (1662–1732) who acquired 300,000 acres and became the richest man in Virginia, and later his cousin, William Fairfax (1691–1757). These men used their inherited wealth to buy more land and become key parts in the shaping of Virginia — this wealth, and influence, was then passed down to family members for generations.

Black Oppression & Resilience in Northern Virginia

The Black experience in Northern Virginia is the story of a battle of wills. Policies of exclusion met with the determination and resilience of the Black community to circumvent barriers and carve out opportunities.

This battle first played out in the fight for 1. freedom itself and later for the rights to 2. build wealth and buy property, 3. obtain an education, 4. find jobs, and 5. win civil liberties. Each of the following five sections highlights that history, helps explain the disparities we see today, and outlines policies that can reverse inequities in these domains.

Freedom & Safety

Freedom of movement is not fully possible when the innocent activities of daily life — from driving a car to entering a store — threaten the physical safety of Black people.

The Black experience in Northern Virginia began without freedoms. Africans first arrived in the 1600s as chattel (property), and the enslaved population grew in numbers in the 18th century. Between 1749 and 1782 alone, the enslaved portion of the Fairfax County population grew from 28% to 41%. Although late 18th century Virginia allowed some enslaved people to gain their freedom, lawmakers tightened their grip in the early 1800s, passing laws to re-enslave free Blacks if they did not leave the Commonwealth and prohibiting Black people (free or enslaved) from congregating.2

Northern Virginia became a center of the domestic slave trade, shipping enslaved Black people from the port of Alexandria to Southern destinations. By the start of the Civil War, Virginia had the largest enslaved population of any Confederate state. Although the 1860s brought an end to chattel slavery and early Reconstruction expanded civil rights, the ensuing backlash of Jim Crow laws and practices terrorized Black families and quashed social, economic, and political rights. In Northern Virginia, those laws and practices affected every aspect of life. Black passengers were beaten on trolley cars for the slightest infractions, the Ku Klux Klan was active, and public lynchings occurred in Leesburg and Alexandria from the late 1870s into the early 20th century.

Freedom of movement is not fully possible when the innocent activities of daily life — from driving a car to entering a store, especially in mostly white areas — induce suspicion, microaggressions, and perceived threats to the physical safety of Black people. The chronic stress this induces among victims of discrimination has known harmful effects on physical and mental health.

Too often, Black people face threats from law enforcement itself. The fraught relationship between the police and Black people dates back to the slave patrols of the 1700s that controlled the movement of Black people and administered punishment. Over time, similar groups enforced Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, which criminalized even innocent behaviors. For example, under 19th century “vagrancy” laws, Black people could be arrested for not carrying proof of employment.

People of color continue to be targeted by police today. According to the NAACP, a Black person is five times more likely to be stopped without just cause than a white person, and many are mistreated or killed. Police misconduct occurs throughout the United States, including Northern Virginia. For example, in 2017, U.S. Park Police pursued, shot, and killed Bijan Ghaisar, a man of Iranian descent, after he drove away from a minor vehicle collision in Alexandria. Racism within the criminal justice system extends beyond policing; it affects convictions and sentencing. In 2016, Black people accounted for 60% of Virginia’s prison population but only 19% of the population at large.

And once Black people acquire a criminal record, they are more likely than white criminals to carry the consequences throughout life. Studies show that white ex-offenders are more likely to be hired than Black ex-offenders.

2. At certain times before the retrocession of 1847, the eastern edge of Northern Virginia was within the boundaries of the District of Columbia, where the Black population enjoyed greater freedoms than those in the Commonwealth.

Leaders in Northern Virginia should ensure that all residents have a voice and can participate in decision-making and leadership. Initiatives aimed at improving the safety of people of color in Northern Virginia are urgent. No group should be victims of hate crimes and violence.

- Particular priorities are addressing systemic racism in law enforcement and criminal justice to eliminate racial bias in apprehension, conviction, sentencing, and incarceration.

- All law enforcement agencies in Northern Virginia should acceler- ate efforts to address implicit bias, eliminate police misconduct, and aggressively prosecute hate crimes.

- Some efforts are already underway. For example, in 2015, Fairfax County created an independent Police Civilian Review Panel and Independent Police Auditor, initiated a body camera program, and launched Diversion First, a program that offers alternatives to incarceration for people with mental illness, developmental disabilities or substance use disorders.

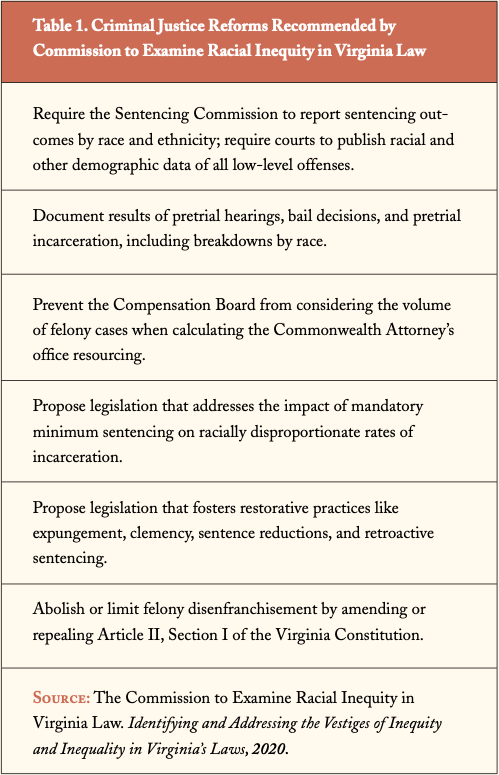

- Sentencing reforms are also necessary, including those recommended in 2020 by Governor Northam’s Commission to Examine Racial Inequity in Virginia Law (Table 1). Restorative justice3 is also necessary for formerly convicted people, including the removal of barriers to housing, employment, and voting.

Displacement is a familiar feature of Black history. Entire communities have been destroyed by invoking eminent domain, the government’s power under the law to take land and even level communities for “the good of the public.” This authority has been used to build government facilities, highways, and even private single family homes on land where Black families once lived. Black communities have also been displaced by gentrification, which has priced families out of neighborhoods they’ve occupied for generations.

Joplin & Batestown (1800–1940’s)

- In 1800, more than 40% of Prince William County’s residents were enslaved. However, freed Black people, such as Henry Cole — the largest Black landholder in Prince William County — and Sally Bates, established 19th century communities such as Batestown and Joplin.These enclaves disappeared completely by the 1940s when the federal government evicted residents to establish a recreational area that would become Prince William Forest Park.

Queen City/East Arlington (1890’s–1942)

- When the Federal government closed Freedman’s Village, many of its residents moved to other Black enclaves in Arlington, among them Queen City and neighboring East Arling- ton. The roads were unpaved and lacked street lights, sidewalks, curbs and gutters. Many households lacked electricity or sewer pipes. Nevertheless, by 1940, East Arlington was a vibrant community, home to 903 individuals and 218 households. In February 1942, as part of the construction of the Pentagon, the federal government condemned Queen City and East Arlington to build a highway cloverleaf near the facility. The residents were given until March to evacuate, a nearly impossible task, especially because wartime housing in the area was extremely limited. With much petition and lobbying on their behalf by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the government provided the families with temporary trailers in nearby Johnson’s Hill and Nauck until they could find permanent housing.

Freedman’s Village (1863–1900)

- When President Abraham Lincoln passed legislation in 1862 to free all those who were enslaved in the District of Columbia, large numbers of enslaved peoples started to flee to the District. In 1863, the government chose the site of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Arlington plantation to establish Freedman’s Village, a community for Black people seeking protection and to avoid a potential humanitarian crisis. Support for the Village shifted after the war, and the government tried many times to close what had become a thriving Black community. They finally succeeded in evicting the population in 1900. The site is now part of Arlington National Cemetery.

Fort Ward, Macedonia, & Seminary (1870’s–1960’s)

- Named after its location on the remains of a Civil War fortification, Fort Ward, “The Fort’’ was a small Black community that emerged in the 1870s in what was then eastern Fairfax County. Because of its close proximity, The Fort was also part of the larger Fairfax Seminary community, which consisted of both Black and white residents, and an area known to Black residents as Macedonia. But in the 1950s and 1960s, Alexendria started buying the property of Black residents to establish the Fort Ward Park and Museum as part of the city’s celebration of the 100-year anniversary of the Civil War. And to enable the construction of T.C. Williams High School, named after a racist school superintendent who fought desegregation, the city invoked eminent domain to uproot the residents of Macedonia.

Wealth Building & Property

In a country where land is the prime financial asset for wealth-building — policies have persistently thwarted the efforts of Black families to buy and retain land or homes.

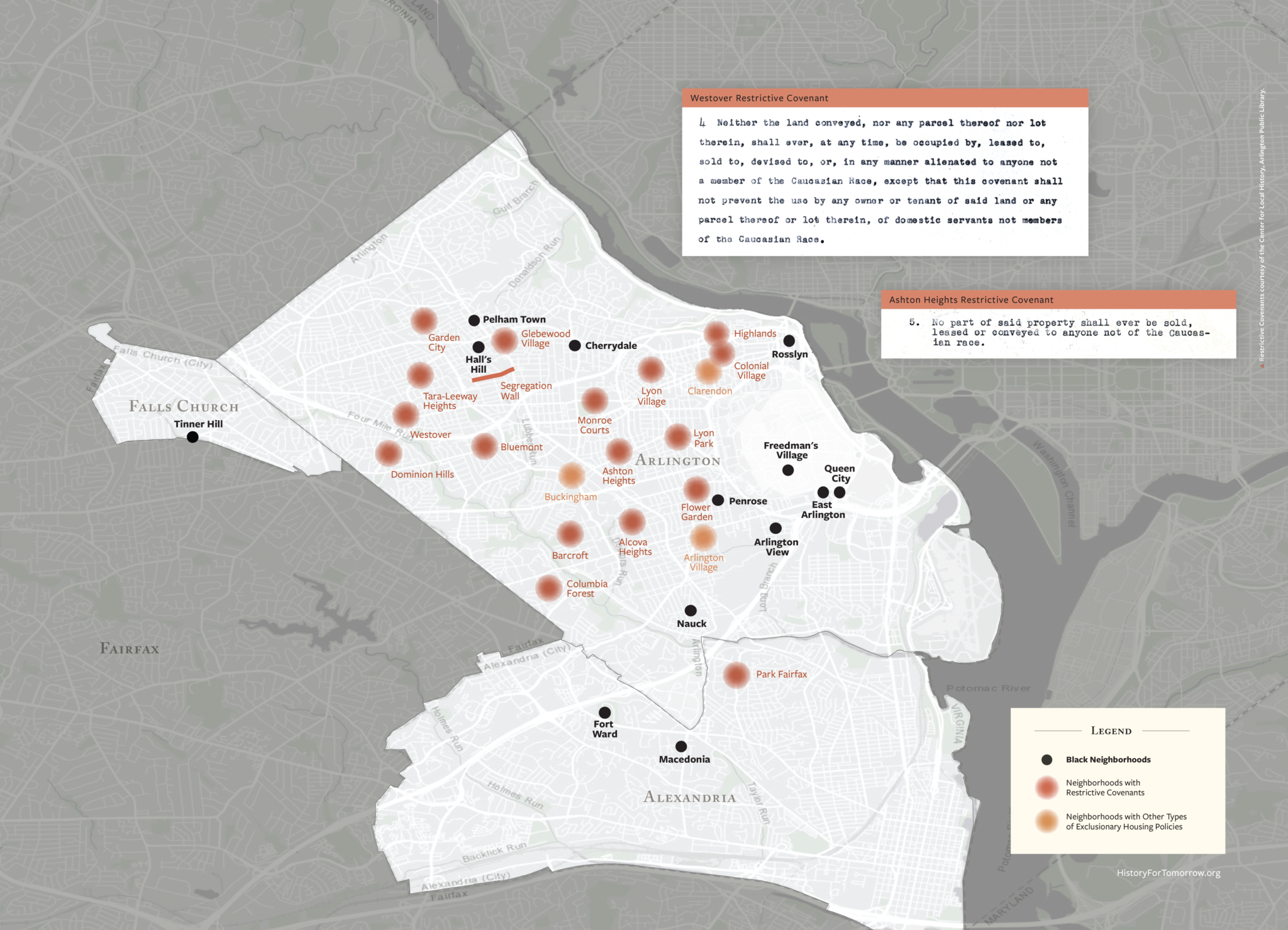

The Black-white wealth gap has lasted generations because —in a country where land is the prime financial asset for wealth-building — policies have persistently thwarted the efforts of Black families to buy and retain land or homes. This was never for lack of effort by prospective Black property owners. In the 1800s, formerly enslaved Black families were eager to buy land, build houses, and open businesses. They built dozens of enclaves, stretching from western Prince William County to the Alexandria waterfront.4 However, when the turn of the 20th century brought expanded railroad, trolley, and road service from the District of Columbia into Northern Virginia and heightened demand for suburban housing, developers and politicians aggressively sought land belonging to Black families. In 1912, Virginia authorized “segregation districts,” making it legal for local governments to segregate neighborhoods, an action taken by the city of Falls Church in 1915. When the U.S. Supreme Court banned such ordinances in 1917, white communities in Arlington County and Fairfax County enacted restrictive covenants that prohibited sales to “non-Caucasian” buyers. Zoning policies, discriminatory lending practices that prevented Black buyers from obtaining mortgages, pricing pressures, and physical threats kept Black families from buying property in more affluent white areas and segregated the Black population into smaller enclaves.

White communities figuratively and literally walled off these Black enclaves. Still standing today are remnants of a wall that white residents of Arlington’s Waycroft-Woodlawn neighborhood built in the 1930s to separate themselves from the adjacent Black community, Hall’s Hill-High View Park.

White control of public utilities and transportation stifled economic growth in Black communities. Decades after paved roads eased access to white subdivisions, Black communities were still served by dirt roads and went without municipal services such as sewage, water, and street lights. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was common for residents of Black enclaves like Hall’s Hill to place lanterns in their windows to light the streets at night.

Black homeowners with limited educational opportunities, few job options, and depreciating property values often lacked the finances to modernize their homes. Federally subsidized mortgages that became available in the 1930s were approved almost exclusively for white buyers and routinely denied to Black buyers, especially those seeking homes outside of “redlined” areas.5 The disinvestment and resulting housing decay in Black neighborhoods played into the hands of developers and politicians, who rebranded Black enclaves as “blight,” cited violations of housing codes, and authorized developers to clear Black properties for new construction. By World War II, suburban development, restrictive covenants, and discriminatory lending had pushed Arlington’s once widely dispersed Black population into three small enclaves, and the 19th century Black communities that once dotted Fairfax County and Loudoun County were gone.

The G.I. Bill widened the wealth gap by helping a generation of white veterans obtain college tuition and home loans to launch middle-class lives, while greatly limiting those opportunities for Black veterans.6 Despite the housing boom, Northern Virginia’s supply of housing that is affordable did not keep pace with population growth. The growth of largely white suburbs in the outlying areas of Northern Virginia led to the expansion of interstate highways throughout Northern Virginia. Planners routed these highways through Black neighborhoods, creating corridors of low-priced property, especially along Shirley Memorial Highway and Interstate 95, which were zoned for high-density housing. In the 1960s and 1970s, people of color came to represent a larger share of the population along these corridors, occupying the garden and tower apartment communities of West Alexandria (Shirley-Duke, Beauregard) and the no-frills housing subdivisions that were built along Interstate 95 in Prince William County between Woodbridge and Dumfries. It is in these census tracts that Northern Virginia’s largest Black populations are now located. In some of these tracts, Black people account for approximately half of the population. The census tracts with Northern Virginia’s lowest life expectancy (75 years) are also here. In many of the census tracts lining the interstate corridor of West Alexandria and Prince William county, median household income is below $70,000 per year and is as low as $49,786 per year in one Dumfries tract.

White families in high-income areas of Northern Virginia have benefited to varying degrees from inherited wealth. Although some people of high socioeconomic status worked their way up from poverty, a large number of successful white families benefited from the property ownership, education, savings, promotions, and other systemic advantages that societal structures offered their parents and prior generations. Many Black people of the same era were systematically denied these resources for upward mobility and, lacking the transgenerational transfer of wealth that occurred in successful white families, were often at an economic disadvantage before they were even born. The widening of the Black-white wealth gap that occurred after World War II was less about determination, resilience, and hard work — which existed in all racial groups — than the structural conditions set by society, often rooted in systemic racism, and the insidious ways wealth inequality has been allowed to compound over time.

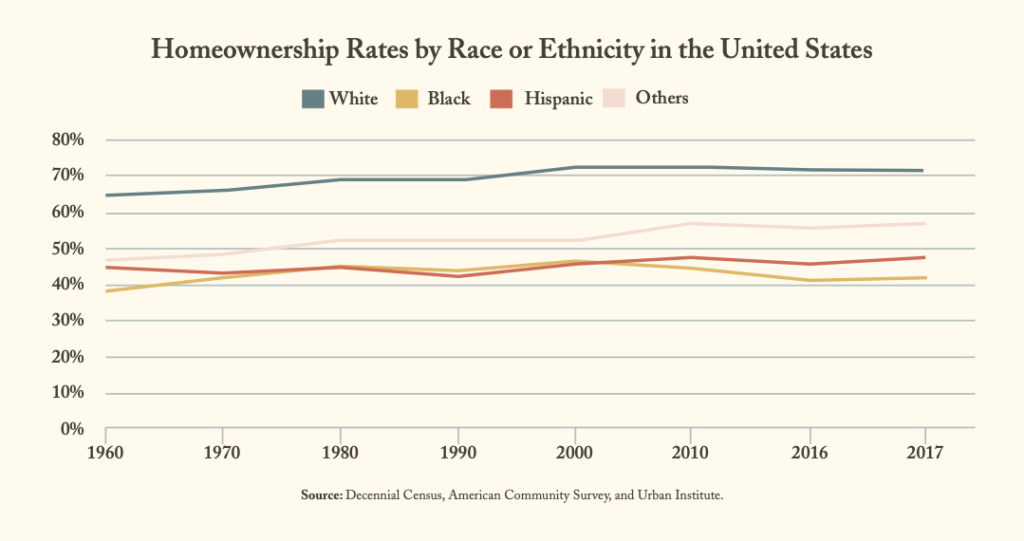

Although the Fair Housing Act of 1968 brought major reforms to housing discrimination based on race, the practice did not disappear and has, instead, evolved into what exists today. As of 2017, prospective Black homeowners were denied mortgages at a rate 80% higher than that of white applicants. The gap between Black and white homeowners is even wider today than it was in 1960. Although gains in Black homeownership rates were made in the decades after the Fair Housing Act, they were erased in the 21st century. Black people were more vulnerable than whites to predatory lending, were more likely to fall victim to the 2008 housing market crash, and benefited less from the economic recovery that followed the Great Recession.

The rising costs of homes in Northern Virginia remain a major problem for low- and moderate-income families. Two-thirds of low-income Northern Virginians are “severely burdened” by the cost of housing and over half of burdened households are non-white.

This signals two things: that the area has an insufficient supply of housing that is affordable and that the current distribution of wealth denies many residents the income they need to cover the cost of living. Zoning policies have also contributed to racial segregation. By setting aside large parts of the region for high-price, single-family housing, and because racially discriminatory policies limit the wealth of Black households, zoning laws serve to exacerbate racial segregation. Pricing pressures continue to restrict property ownership among Black families who lack the inherited wealth of white buyers. Today, many neighborhoods in Virginia are more racially segregated than they were 50 years ago. In sum, today’s low rate of Black homeownership, racial disparities in access to market-rate housing, and the places where those homes are concentrated, can be traced to sustained and deliberate historical forces.

- In the early 1800s, formerly enslaved people established a number of Black communities in Alexandria such as “The Bottoms,” “Hayti,” “The Berg,” and “Uptown.”

- Redlining takes its name from a practice of the Federal Housing Administration, beginning in the 1930s, to deny mortgages in areas near Black populations, often shaded red on maps, while subsidizing mortgages in white areas.

- By extension, the G.I. Bill’s preferential support for white students served to underwrite historically white colleges and universities at the expense of historically Black schools, which were already underfunded.

Policies to reduce racial inequities in wealth distribution and property ownership in Northern Virginia are a recognized priority of state and local governments.

- For example, in 2020 a Governor’s commission recom- mended imposing state limits on exclusionary zoning in localities, adopting more effective inclu- sionary zoning, and increasing allocations to the Virginia Housing Trust Fund, which provides low-interest loans for housing projects.

- Local jurisdictions and the private sector — including developers and investors — must pursue efforts to broaden access to housing that is affordable, including promoting the development of mixed-in- come neighborhoods and limiting requirements for single-family, detached homes. In 2019, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments set worthy targets for the optimal amount, location, and cost of new housing units, which local governments should embrace.

- Land banks, which exist else- where in the Commonwealth, can transform vacant, abandoned property into productive use.

- The financial sector can help by expanding access to full-service banking in communities of color and abolishing discriminatory and predatory lending practices.

- Low-income families require more assistance to maintain housing stability, a need that local governments in Northern Virginia have been working to address. For example, Arlington County’s initiative, Housing Arlington, has created funds for affordable housing investment and county loans, established a housing conservation district with market-affordable housing, and arranged rental assistance for low-income households. Other counties in Northern Virginia are also working to address the hous- ing crisis, although all acknowl- edge that more must be done.

- Jurisdictions should expand enrollment in housing choice voucher programs, and ensure that such vouchers provide access to decent, stable housing by, for example, requiring or incentiv- izing landlords to accept them. State and local jurisdictions should also develop more com- prehensive programs to prevent evictions and their consequences, and should pursue reforms of landlord-tenant laws.

- More systemic policies are needed to address the racial wealth gap. One promising strategy being explored in many U.S. cities is to invest in “baby bonds,” which are held in trust until children reach adulthood. Municipalities can also target reparations toward housing needs. For example, the city of Evanston, Illinois awarded $25,000 to eligible Black households to be used for home repairs or as down payments on property.

A Closer Look: South Arlington

The areas now known as Nauck and Arlington View once consisted of plantations. After the Civil War, freed slaves bought land and built communities in what was then known as Green Valley and Johnson’s Hill, respectively. When rail service arrived at the turn of the 20th century and Green Valley expanded into Douglass Park, it became Arlington’s largest — albeit highly segregated — Black community.

Black people were unwelcome in surrounding white communities, such as Alcova Heights and Barcroft. For example, in the George Mason Terrace section of Barcroft, a 1945 restrictive covenant prevented people who were not “Caucasian” from owning, leasing, using, or occupying buildings or lots. The county spent little on utilities or road service for the Black community. Water, sewer, and electricity did not reach Johnson’s Hill until 1942, and a dead end was left on Nauck’s 16th Street, effectively cutting off access to the area’s main thoroughfare, Walter Reed Drive.

In the 1940s, Nauck and Arlington View lost land to construction of the Pentagon and Shirley Memorial Highway. Mud from the project was dumped in Johnson’s Hill, and both communities became sites for trailer camps and public housing for displaced Black families. Although residents met these challenges with resilience, as when they formed the nation’s first cooperative to buy public housing projects after World War II, the community’s infrastructure suffered from disinvestment. Roads crumbled and overcrowding increased as Arlington’s Black population, pushed out of other areas, moved there. Nauck’s population grew by more than 17% between 1950 and 1960. A 1966 Washington Post article described its homes as “little more than shacks,” noting white middle-class homes that stood across the street. Rising housing costs made it too costly for Black families to remain. In the 1990s, many sold their land to developers building luxury townhomes, often at prices that were too low to rebuy in the area. Nonetheless, Black people still constitute a substantial share (30% or more) of the population of Nauck and Arlington View, but many live in challenging conditions. Whereas median household income in Arlington County averages $120,071 per year, it is only $70,000–80,000 per year in Arlington View and Nauck and below $50,000 per year in two Douglass Park census tracts, too little for Northern Virginia’s high cost of living. Decades of segregation and disinvestment have left their mark. A 2015 article about the wealth divide in Arlington noted that the average price for a home was $417,592 in Nauck but $1.5 million in Lyon Village, where restrictive covenants once banned sales to Black buyers. In a county where life expectancy is as high as 88 years, life expectancy in the Forest Glen neighborhood off Columbia Pike is as low as 77 years.

Education

For generations, Black families have been striving for educational opportunities as a chance at upward mobility, but students of color still face multiple barriers to quality schooling.

For enslaved people, education was a chance at freedom and upward mobility, which is why Virginia forbade education during enslavement.7 After Emancipation, freed Black families quickly established schools for Black students across the region, but they received little support from local government. The 1870 law that established Virginia’s public school system required separate facilities for white and Black children, and Black schools received little funding, thereby ensuring that facilities, curriculum, teacher salaries, and educational outcomes would suffer. Schools for Black children were often one-room, overcrowded buildings that offered few grade levels, “castoff” books and furniture from white schools, outhouses, and little heat. Many Black students who wanted to attend high school

rode trolleys and buses to Washington, D.C. or to the ManassasIndustrial School.

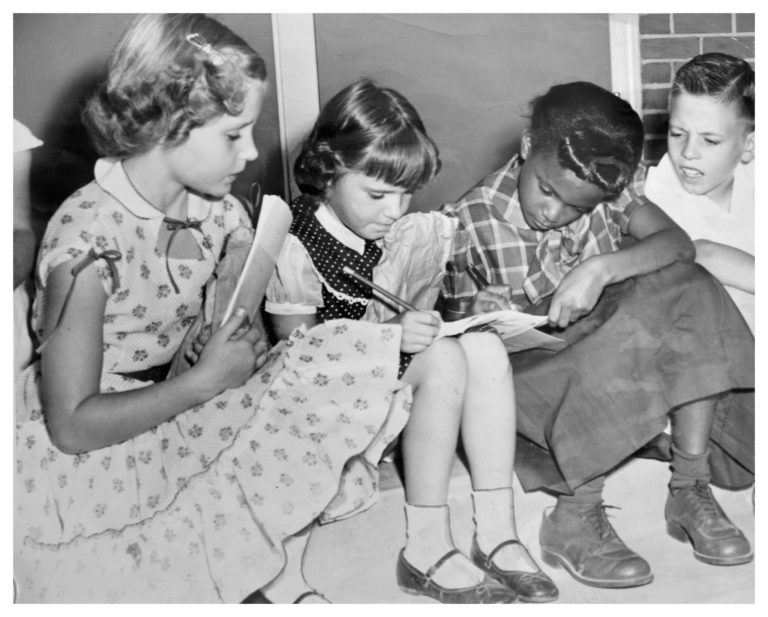

In the 1940s and 1950s, Black parents in Northern Virginia turned to the courts to demand better funding for Black schools and the right to enroll their children in white schools, but progress was slow. Virginia led a group of southern states in a movement known as “Massive Resistance,” refusing to honor Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision that prohibited school segregation. In 1956, Virginia passed “emergency” legislation that empowered the governor to close schools that were under court order to integrate, defund schools that did integrate, and give tuition grants to white parents who enrolled their children in private schools later known as “segregation academies.” A state board limited how many Black pupils could transfer to white schools, citing the psychological burden on white students and other racist criteria. Television news cameras were rolling in February 1959 when four Black children received police protection upon entering Arlington’s Stratford Junior High School, the first Virginia school to desegregate.

Although the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited school segregation based on race, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1974 that school districts were generally not required to desegregate. White parents moved to outlying areas of Northern Virginia where schools had fewer minorities. This “white flight,” combined with exclusionary zoning and housing prices that kept people of color from joining them, heightened the racial segregation of neighborhoods (and classrooms). Although graduation rates among Black students have since increased, educational disparities persist. For example, the proportion of white and Black 8th graders in Fairfax County who passed the 2018–2019 Standards of Learning examination for mathematics was 91% and 74%, respectively. Students of color are more likely to be in schools that are inadequately funded, cannot retain teachers, and offer fewer advanced classes.

School segregation is worsening in Virginia. A student’s zip code matters — educational resources and outcomes are connected to a child’s neighborhood, largely because schools are funded by property taxes. The disparity in local tax revenue for schools, combined with residential segregation, ensures that middle- to high-income, predominantly white school districts, which typically require fewer resources to succeed, receive more funding than schools in low-income, mostly minority neighborhoods with greater needs. In addition to disparities between districts, segregation within districts is also prevalent and is estimated to contribute to at least half of all multiracial school segregation in Virginia.

The ability of Black students to obtain an education is also impacted by society’s tendency to criminalize Black people, which often starts with youth. The “school to prison pipeline” is a major problem in Virginia; in 2011–2012, Virginia schools referred Black students to police and courts at three times the national average. This process starts early; within K–12, school suspension and other forms of punishment disproportionately affect Black students, and carry long-term consequences for educational outcomes. In the 2015–2016 school year, Black students in Fairfax County were three times more likely to be suspended than white students.

Barriers to education continue beyond primary and secondary education. Tuition costs, standardized tests that favor whites, and biased admission policies exacerbate disparities in higher education. Most Black parents have not acquired or inherited the family savings that enable many white families to pay for college, in part because of the barriers they and their ancestors faced in gainful employment and property ownership. As a consequence, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, advances in Black students’ enrollment have been accompanied by some of the lowest persistence rates, highest undergraduate dropout rates, highest borrowing rates, and largest debt burdens of any racial group. In Fairfax County, 74% of white adults, but only 46% of Black adults, hold a Bachelor’s degree. Even with a bachelor’s degree, Black professionals in the United States who are aged 25 to 34 earn 15% less than the average earnings of all bachelor’s graduates of the same age, and their unemployment rate is two-thirds higher. These economic challenges, in turn, affect their ability to afford housing and the high cost of living in Northern Virginia.

7. More educational opportunities were available to Black students in the District of Columbia which, until 1846, included parts of Alexandria and Arlington County.

School districts in Northern Virginia should strengthen initiatives to reduce dropout rates among students of color, increase high school graduation rates, and prepare students adequately for college or vocations.

- State and local governments can promote policies at the school district level by working to adjust attendance boundaries to increase diversity, update funding formulas to deal adequately with fiscal needs, invest adequately in under-resourced school divisions, and expand broadband access throughout Northern Virginia.

- More proactive efforts are needed to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline and address racial bias

in disciplinary suspensions, such as abolishing zero-tolerance policies, eliminating punishment for subjective offences, removing police officers from schools, and implementing programs for restorative justice. Fairfax County, for example, has focused on supporting positive behavior, increasing availability to appren- ticeships and career academies that provide work experience, and expanding advanced academic programs; other jurisdictions should consider similar strategies. - An important goal that can reduce bias in disciplinary suspensions and improve educa- tional outcomes is to increase the diversity of the teacher workforce, which in many Northern Virginia jurisdictions is overwhelmingly white. Increasing the likelihood that students of color will interact with teachers who look like themselves is known to improve educational outcomes.

- Maintaining a diverse workforce requires not only hiring more teachers of color but also enacting policies to retain them, such as easing debt burdens, changing the school culture to create a more welcoming climate for teachers (and students and families) of color, and requiring recurring cultural-competency training as part of the teacher certification process.

- Students of color may also benefit from mentorship pro- grams, as studies suggest that a student’s personal connection with a teacher or another adult may influence college persistence and success.

- Expanding access to early childhood education and address- ing health inequities among students of color are also effective strategies to improve educational outcomes. Several Northern Virginia jurisdictions are explor- ing the feasibility of community school or “whole school” models that address the social, emotional, physical, and academic needs of students.

- Initiatives to prioritize access to college for students of color — including reducing tuition costs, addressing biases in standardized testing and admission decisions, providing free two-year college, and reducing student loan burden — should be implemented. And Governor Northam’s proposal for a tuition-free community college program for low- and middle-income students should move forward.

Black history is a story of resilience in defiance of displacement and discrimination. From the 1800s onward, Black families have been determined to establish communities and open businesses, churches, and schools. With little help from local governments, and often deprived of basic utilities such as electricity or plumbing, Black residents came together to find solutions. Oral histories from residents of these communities tell stories of folks looking out for one another and a strong sense of community.

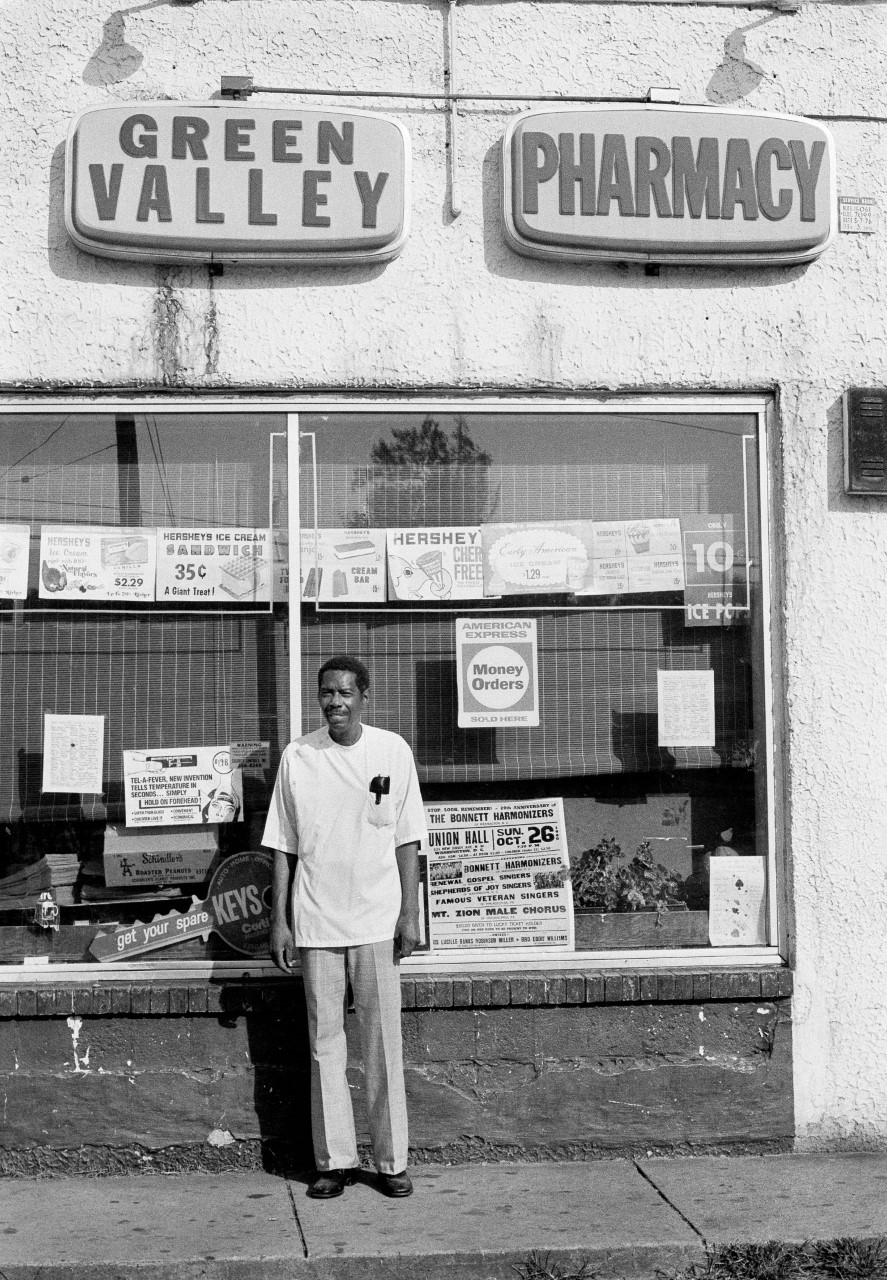

- Levi Jones, whose parents were enslaved by George Washington, bought land in Green Valley and built a house in 1844. His family and the Black settlers who followed after the Civil War were resourceful in accumulating property and building a thriving Black community that included churches and schools. The success stories included William Augustus Rowe, a former slave who became a district representative; Selina Gray, the former maid for Robert E. Lee’s wife, who acquired land that became “Gray’s subdivision” in 1913; her son Harry Gray, a mason who had a 30-year career in the U.S. Department of the Interior; and Howard University School of Pharmacy graduate Leonard “Doc” Muse (pictured above) owner of Green Valley Pharmacy, a fixture of the Nauck community and likely the first Black-owned pharmacy in Arlington. Muse opened the pharmacy in 1952, during a time when most pharmacies did not welcome the Black community.

- The success of the prominent Syphax family of Arlington began when George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington, manumitted his enslaved maid, Maria Carter Syphax. The Syphax family acquired 17 acres of his Arlington plantation in 1866, where they built a house and farm. Maria’s son William went on to work in the U.S. Department of the Interior, and John served as a delegate to the Virginia legislature.

- When the Union Army occupied Alexandria early in the Civil War, the Black community began opening schools at a remarkable speed, led by women such as Anna Bell Davis, Mary Chase, Jane Crouch, and Harriet Jacobs. The Columbia Street School and Saint Rose Institute opened in 1861; the First Select Colored School, Beulah Normal and Theological Institute, and Leland Warring school in 1862; the Union Town School, Sicles Barracks School, and Newtown School in 1863, and the Jacobs Free School in 1864.

- Students at the Fairfax African American school, established

in the 1870s, used an outhouse and relied on a pot-bellied stove for heat; in the winter, the students’ dedicated teacher, Minnie Hughes, was known to pour hot water from a kettle to warm their hands. Hughes received no regular pay until 1916, and then received $8 per month.

- Some Black contractors built homes for Black families that white builders turned away. Two formerly enslaved men, Henry Holmes and William Butler, became developers, building the Butler-Holmes subdivision in the Penrose section of Arlington in 1882. And Richard Drew, an Arlington carpenter, put his son through medical school. Dr. Charles Drew (1904–1950) pioneered blood transfusion for the military and became known as “the father of blood banking.”

Jobs

In a pattern that has lasted generations, Black jobseekers have often found themselves at the bottom of the employment ladder, confronted by a white society that resisted their upward climb.

Freed Blacks were eager to find jobs, earn money, and buy land, but — in a pattern that has lasted generations — often found themselves at the bottom of the employment ladder, confronted by a white society that resisted their upward climb. Black people have faced formidable barriers to employment, including limited access to education, fewer job options, and racial prejudice in hiring, salary, and promotions. After the Civil War, most found jobs in unskilled labor or domestic work, while others used skills learned during enslavement or vocational training to work in trades. They worked at the shipyards on Alexandria’s waterfront, Arlington’s brickyards, and the dairy farms, mills, and estates in Fairfax County.

Some opened their own small businesses catering to customers who were unwelcome in white establishments. Unfortunately, white violence, especially in the early 1900s, destroyed many thriving Black businesses, along with whatever wealth their owners had accumulated. Many Black workers found stable employment in the federal government as clerks or in other low-level civil service jobs, but they often earned too little to accumulate wealth. In 1938, about 90% of Black federal workers in Washington, D.C. were custodians.

As the late 20th century brought a shift from manufacturing to a knowledge economy, the Black population was at a distinct disadvantage because of systemic barriers to education (see earlier) and the hiring discrimination Black applicants faced even when they were qualified. This continues today. Even with similar resumes, studies have found that Black workers are far less likely to get called for an interview, and once hired are more likely to experience racism and wage discrimination at the workplace. Black men make 22% less than similarly qualified whites, and Black women make 12% less than white women. Black people are underrepresented in professional schools and well-paying jobs, deepening the Black-white wealth gap. Since 1970, median income for Black households in Virginia has rarely exceeded 70% of the state average. Nationwide, the average wealth of Black households is less than 10% that of white households. While Black Americans constitute 13% of the U.S. population, they hold less than 3% of its wealth.

Tight finances and few savings have left most Black families without an economic cushion for hard times and more vulnerable to food or housing insecurity and compromised health when crises (like the COVID-19 pandemic) occur. What remains is a vicious cycle. As families work hard to create better lives for their children, Black children are more likely than their white counterparts to backslide into a lower economic group as adults.

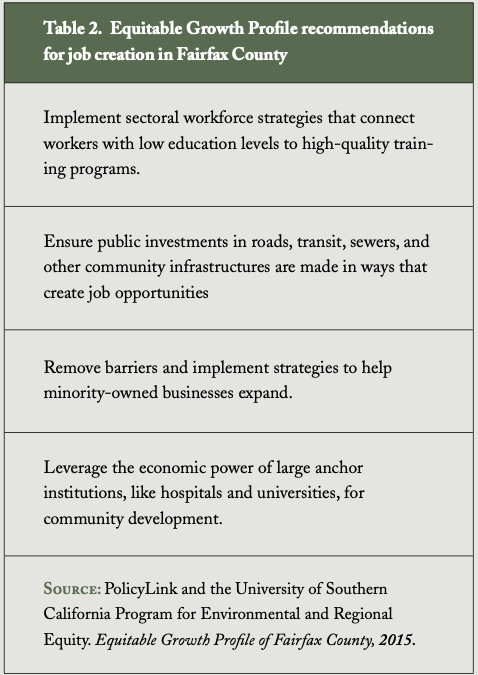

In addition to efforts to improve educational attainment among youth (see earlier education section), vocational training programs are needed to help workers transition to 21st century jobs.

- A study that was conducted for Fairfax County included a number of recommendations for creating pathways to such jobs (Table 2).

- Employers in Northern Virginia can reduce job inequities by observing equal opportunity regulations to eliminate racial bias in hiring and promotions.

- Employers in Northern Virginia can also reduce job inequities by offering workers a wage that keeps pace with the region’s high cost of living, adequate and affordable health insurance, and employ- ee-sponsored retirement programs. Policies to address the loss of such benefits in the gig economy are increasingly important.

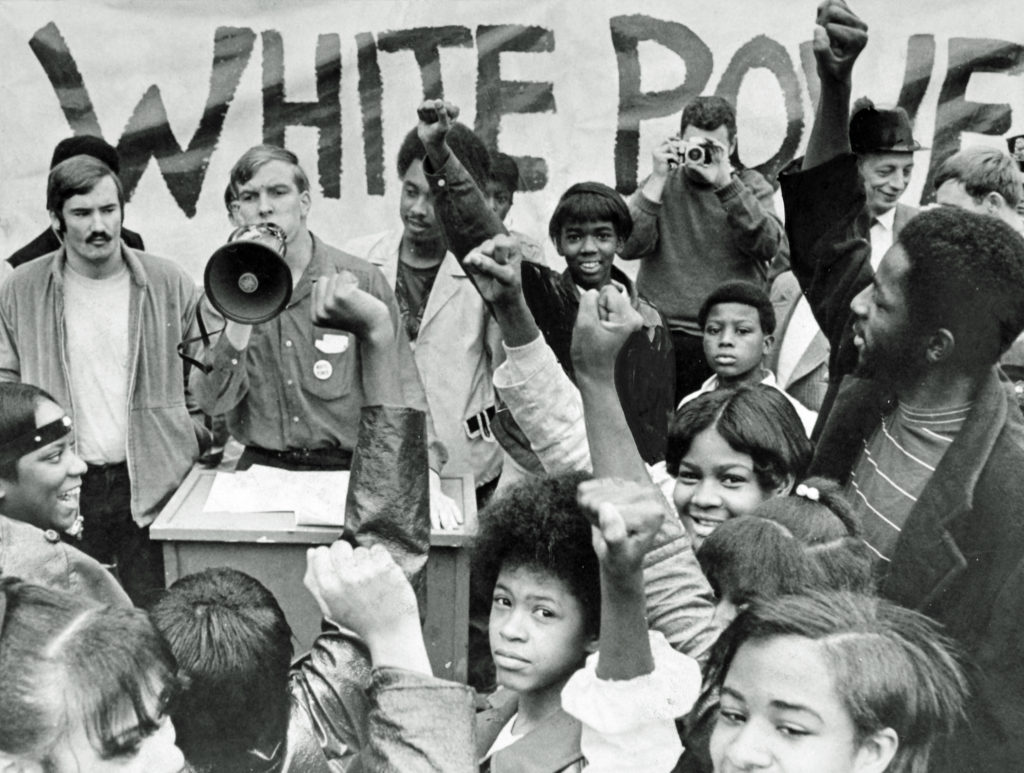

- In the summer of 1960, Dion Diamond, a civil rights activist and student at Howard University, sat at the “whites only” lunch counter in Arlington.“We desegregated that entire area within two weeks, and I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but there’s this picture. In fact, it’s in the closet. George Lincoln Rockwell, of the American Nazi Party, came in and surrounded us as we had the sit-in, and it was just amazing. I’m surprised that I didn’t panic. It’s amazing when you’re young and reckless. I call it youthful exuberance.” — Dion Diamond

- In October 1966, in an effort to garner public attention to the housing crisis, hundreds of protesters marched along the I-495 Beltway and other major thoroughfares and through segregated neighborhoods, holding sit-ins and picketing private apartment developments to demand “Equal Opportunity Rentals.”

- In February of 1959, four students from the nearby Hall’s Hill neighborhood stepped into Stratford Junior High School in Arlington and became the first students to desegregate a public school in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The historic day came after years of pressure from Black parents and the NAACP, who fought for their children’s access to better schools.

- In the late 1800s, Joseph and Mary Tinner bought land in Falls Church. In the early 1900s, Joseph Tinner and E.B. Henderson fought local segregation laws and founded the first rural branch of the NAACP in the United States. Tinner served as president. The construction of Lee Highway was routed through this enclave in the 1920’s.

- In a staged event in 1939, five Black men were arrested for reading books in Alexandria’s whites-only library, prompting the city to open a library for Black patrons.

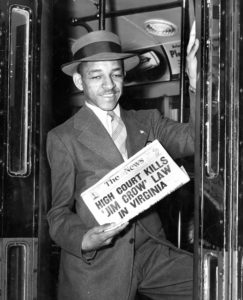

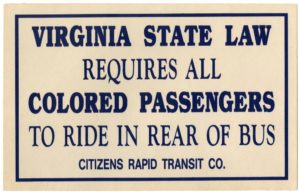

- In 1946, three months after the U.S. Supreme Court banned segregation on interstate public transport (Morgan v. Virginia), a Black commuter, Lottie Taylor, sat in the front of a bus traveling from Washington, D.C. into Northern Virginia. Taylor was forcibly removed by Fairfax Police and charged with disorderly conduct, but she won the case in the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (Taylor v. Virginia).

- Such legal successes met with backlash. The Klan resurged in the 1950s and the American Nazi Party was founded in Arlington. In 1960, Nazi enthusiasts confronted Black activists at lunch counter sit-ins in Arlington.

Civil Liberties

The right to free speech, privacy, the ballot box, and fair court trials has never been fully extended to Black communities.

Civil liberties include the right to free speech, privacy, the ballot box, and fair court trials, among others. These liberties have never been fully extended to Black communities. Emancipation and Reconstruction won temporary civil liberties for the Black population, but as early as the 1870s, Virginia passed laws to suppress votes by imposing poll taxes and literacy tests and denying votes to men convicted of petty crimes. After the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Plessy v Ferguson, permitted segregation of public facilities that were “separate but equal,” the pace of Jim Crow laws and practices intensified.

Virginia adopted a new constitution in 1902 with the goal of Black disenfranchisement and got immediate results. The number of eligible Black voters in Virginia dropped from 147,000 in 1901 to about 10,000 in 1905. Virginia legalized segregation of trolley cars, trains, prisons, and public events. Black-white intermarriage, which had been banned for centuries, was elevated to a felony crime. The Klan became more active in the 1920s. In 1930, Arlington politicians changed voting procedures to prevent Black candidates from taking office.

As these attacks on civil liberties increased, the Black community organized to counteract these efforts. Falls Church activists E. B. Henderson and Joseph Tinner fought against Arlington’s 1915 segregation ordinance and founded the nation’s first rural branch of the NAACP. In a staged event in 1939, five Black men were arrested for reading books in Alexandria’s whites-only library, prompting the city to open a library for Black patrons. In 1946, three months after the U.S. Supreme Court banned segregation on interstate public transport (Morgan v. Virginia), a Black commuter, Lottie Taylor, sat in the front of a bus traveling from Washington, D.C. into Northern Virginia. Taylor was forcibly removed by Fairfax Police and charged with disorderly conduct, but she won the case in the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (Taylor v. Virginia).

Such legal successes met with backlash. The Klan resurged in the 1950s and the American Nazi Party was founded in Arlington. In 1960, Nazi enthusiasts confronted Black activists at lunch counter sit-ins in Arlington. Although the 1960s brought the Civil Rights Act (1964), Voting Rights Act (1965), and the legalization of interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia (1967), racism in Northern Virginia lived on. Northern Virginia realtors “steered” Black buyers from white neighborhoods. They engaged in blockbusting — selling property to Black buyers at inflated prices, agitating white homeowners about their neighborhood becoming a “slum,” and then buying their homes at below-market prices.

Today, discrimination and implicit bias persist in most facets of modern life and, as noted earlier, these stresses are harmful to health. Recent years have brought greater attention to institutional racism — such as its role in police misconduct, sentencing, and mass incarceration — but it persists and continues to claim lives. Throughout U.S. history, restricted access to the ballot and political office has prevented Black people from holding power and implementing policies to help their communities. Although we no longer see literacy tests and poll taxes, more subtle forms of voter suppression continue and are increasing in many states. People of color now face a resurgence in white supremacy and political efforts to erode civil liberties.

The Commonwealth of Virginia and Northern Virginia jurisdictions should actively oppose efforts to roll back existing civil rights protections and continue working toward social justice for people of color.

- In sharp contrast to disturbing trends in other states, the Commonwealth recently passed laws to expand voting rights, such as repealing the state’s voter ID law, permitting 45 days of no-excuse absentee voting, making Election Day a state holiday, and enacting automatic voter registration when driver’s licenses are issued.

- Restoring voting rights to formerly incarcerated people and ending gerrymandering remain unfinished business.

- A number of government agencies, corporations, and other employers are taking steps to help reduce discrimination by conducting implicit bias training and applying an equity lens to their practices.

- These efforts can be expanded to include introspective audits to assess the degree of discrimination to which employees and clients are exposed and to identify potential remedies.

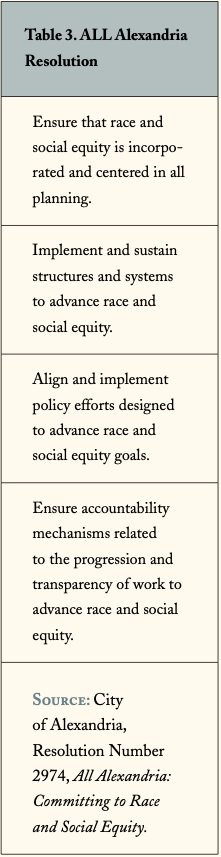

- Local governments have already begun this effort. For example, in 2017 the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors and School Board adopted One Fairfax, a policy to “consider equity in decision-making and in the development and deliv- ery of future policies, programs, and services.” The policy focuses on 17 areas, including community and economic development, hous- ing, education, environment, and transportation. In January 2021, the city of Alexandria adopted the ALL Alexandria Resolution to emphasize equity in public policy.

- Other Northern Virginia juris- dictions should take similar steps, while also conducting racial equity audits of proposed legislation and budgets.

Conclusion

The first step in addressing racial inequities in any community is to acknowledge the past, with honest and full transparency. It is important for the residents of Northern Virginia, and their leaders, to understand and come to terms with the history of the oppression and accomplishments of Black people, as this report has attempted to review. Such introspection is necessary to expose the vestiges of systemic racism, both in outdated laws that remain “on the books,” in current and proposed policies, and in misguided narratives about the origins of disadvantage and poor health in communities of color. The lesson of history is clear: if past policies created those inequities, today’s policies can change the future. And while federal policy contributed to, and still shapes, local dynamics, that should not stop local governments and stakeholders from acting now on their own equity agenda.

Bold action is required to redress embedded structures of racial hierarchy, and both white and non-white people must come together to reimagine systems that emphasize fair and respectful treatment of everyone, regardless of background. The work must involve data analysis to identify gaps and authentic engagement of communities in devising solutions that respect their lived experiences. The history of Northern Virginia records atrocities and discrimination but also documents the inspiring resilience and resourcefulness of people of color to overcome barriers to opportunity and build better lives for themselves and their children. As reflected in the slogan, “Nothing About Us Without Us,” meaningful solutions to improve equity must be designed with everyone at the table. Working together — with collective action, persistence, and resolve — Northern Virginia can make racial inequity a thing of the past.

Recommended Reading

This report is drawn from more than 100 sources and documents. Please visit the document on our website for full access to detailed citations.

A view from Hall’s Hill: African American community development in Arlington by Lindsey Bestebreurtje. Published in 2015 in Arlington Historical Magazine (15:3, pages 19–32).

Built by the People Themselves: African American Community Development in Arlington, Virginia, From the Civil War Through Civil Rights by Lindsey Bestebreurtje. Doctoral dissertation for George Mason University, 2017.

Beyond the plantation: freedmen, social experimentation, and African American community development in Freedman’s Village, 1863–1900 by Lindsey Bestebreurtje. Published in 2018 in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (126:3, pages 334–365).

A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County, Virginia, 2nd ed. Produced in 2016 by the Department of Community Planning, Housing, and Development, Arlington, VA.

Black resilience in Alexandria website published in 2020 by Nia Jordan (https://tinyurl.com/4b9h6ub7).

Finding the Fort: A History of an African American Neighborhood in Northern Virginia, 1860s–1960s by Krystyn R. Moon. Report for the Office of Historic Alexandria, 2014.

The African American Housing Crisis in Alexandria, Virginia, 1930s–1960s by Krystyn R. Moon. Published in 2016 in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (124:1, pages 28–68).

Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon by Nancy Perry. Published in 2015 in Urban Geography (37:1, pages 1–21).

We didn’t have any other place to live: residential patterns in segregated Arlington County, Virginia by Nancy Perry, Spencer Crew, and Nigel M. Waters. Published in 2013 in Southeastern Geographer (53:4, pages 403–27).

African American life in Arlington, Virginia, during segregation: a geographer’s point of view by Nancy Perry. Published February 21, 2019 in The Metropole.

Building the Federal Schoolhouse: Localism and the American Education State by Douglas S. Reed. Published in 2014 by Oxford University Press.

Free Negroes in Northern Virginia: An Investigation of the Growth and Status of Free Negroes in the Counties of Alexandria, Fairfax and Loudoun, 1770–1860 by Donald M. Sweig. Doctoral dissertation for George Mason University, 1975.

Freedom is Not Enough: African Americans in Antebellum Fairfax County by Curtis L. Vaughn. Doctoral dissertation for George Mason University, 2014.