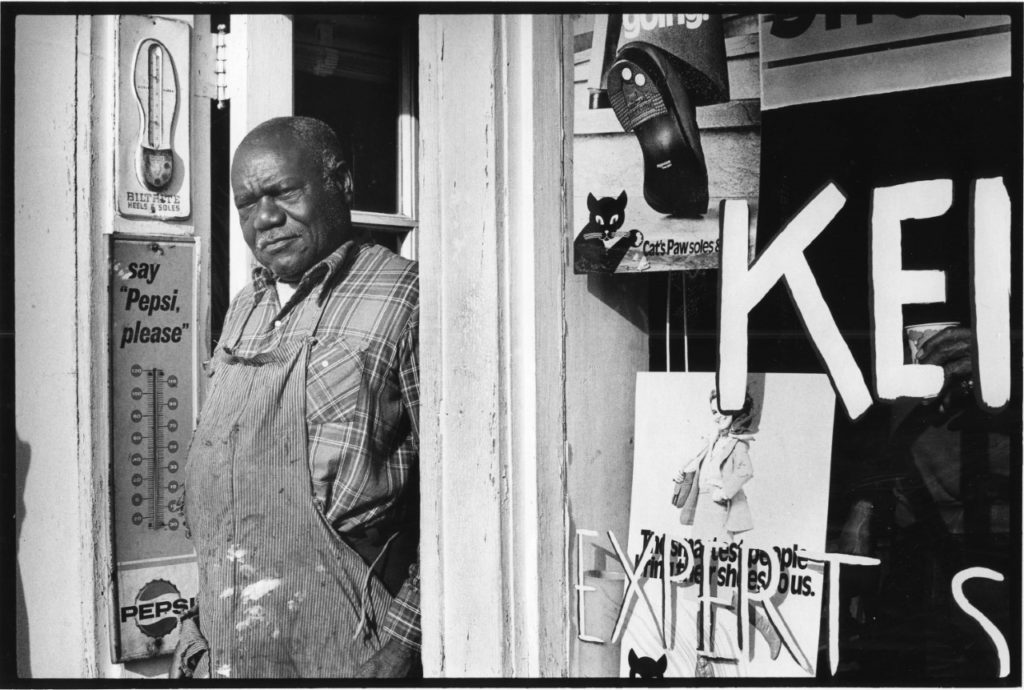

When Leonard Muse (1923-2017) was young, a neighbor asked him to go to the pharmacy to fill a prescription. When he arrived, he was tired and sat down to wait for the prescription to be filled. But he was immediately told, “you can’t sit there.”

He later recalled this incident in an interview with Arlington Library’s Center for Local History. “So, I went out and sat on the sidewalk until they filled the prescription. And I had the idea, I said, well, we need a pharmacy where we can sit wherever we want to –”.

And so he did. He studied pharmacy at Howard University, got his degree in 1948, and in 1952, along with his business partner Waverly Jones, “Doc” Museopened Green Valley Pharmacy at 2415 Shirlington Road. The pharmacy served predominantly Black customers in this historic neighborhood, founded by freed slaves in the 1800s. But his business also functioned as a gathering place for Black patrons who were largely unwelcomed in white neighborhoods, and included a lunch counter that provided free meals every Wednesday. It may have been the first Black-owned pharmacy in Arlington.

The pharmacy remained open until 2017, closing shortly after “Doc” Muse’s death. He was 94 years old.

In Response To Jim Crow

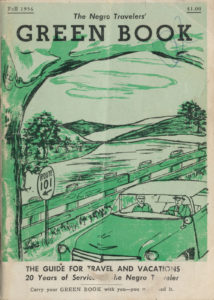

Much like Doc Muse’s pharmacy, many Black businesses opened in response to Jim Crow segregation. In an era when many white-owned businesses refused to serve Black patrons, there was great need for pharmacies, stores, and other businesses to meet the basic needs of the Black community. It also provided a vital source of income for many Black families. According to historian Nancy Perry, Black business entrepreneurs rarely had the resources to operate a large business, so they opened small restaurants, corner stores, repair shops, barbershops, and beauty salons serving clientele who were unwelcome elsewhere. It’s estimated that 80% of Black businesses were in the owner’s home.

As was true at the time across the country, hospitals in Arlington were segregated, service to Black patients was inadequate, and there were few doctors of color. In Arlington, Black mothers were barred from the hospital’s maternity ward and were expected to travel to Washington D.C. or Alexandria to give birth. But for many, traveling to the neighboring areas was difficult, especiallyin a medical emergency.

In 1947, Ralph Collins founded the Friendly Cab Company to help. Many of the drivers were off-duty Black firemen wholived locally. They took patients to destinations all over the region, including Freedmen’s Hospital, located on the grounds of Camp Barker, and John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. The Friendly Cab Company still operates today under the same family and serves Arlington.

Some Black contractors built homes for Black families that white builders turned away. Two formerly enslaved men, Henry Holmes and William Butler, became developers, building the Butler-Holmes subdivision in the Penrose section of Arlington in 1882. Richard Drew, an Arlington carpenter, put his son through medical school. Dr. Charles Drew (1904-1950) pioneered blood transfusion for the military and became known as “the father of blood banking.”

These success stories, however, were exceptions, and serve to highlight the types of opportunities lost when populations are denied basic resources like education, housing, and income. As noted by historian Krystyn Moon, “poverty, a lack of education, and racism greatly limited their opportunities and propelled many into a cycle of debt. Without some kind of capital, former slaves initially did not have the money to invest in businesses, land, homes, or farms, and without an education, White-collar positions were unattainable.”

Post Civil Rights / Segregation

Civil rights legislation was passed in the 1960s, creatingmore employment opportunities for Black people and banning many forms of segregation. After the mid-1960s, Black enrollment in colleges increased dramatically, graduates were less interested in owning small businesses, and many Black-owned businesses disappeared.

Many of Arlington’s Black communities also disappeared. Rising prices, redevelopment, and exclusionary policies forced many Black families to leave Arlington to find more affordable housing. The population of historically Black neighborhoods such as Hall’s Hill, Green Valley, and Johnson’s Hill began to decline in the 1950s. Between 1950 and 2000, the proportion of Black residents in Johnson’s Hill dropped from 100% to 63%.

Many Black businesses disappeared. While Black residents began to patronize white businesses, many white folks did not patronize Black businesses, which could have sped up the decline of these businesses.

The legacy of Black-owned businesses remain, as do some of the iconic establishments of the era. The funeral home that James Elwood Chinn opened in Green Valley in 1942 is still serving customers. And the determination of communities of color to improve their economic wellbeing, despite the continued challenges of discrimination and implicit bias, remains vibrant today–in the professions, business, government, and the armed services. Although disparities in hiring, promotion, and wages persist, many people of color whose ancestors could only afford to open a corner store are now corporate executives and business leaders.