On the morning of February 2, 1959, Ronald Deskins, a 12-year old boy in Arlington, was very nervous about his first day of school. While changing schools mid-year is nerve-wracking for any student, Deskin had other worries that were hardly normal — like being spit on or his father’s car being stoned by protestors.

As one of the first students to participate in the desegregation of public schools in Virginia, one can understand why he was so worried.

Five years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision that banned school segregation, four Black students from the Hall’s Hill neighborhood in Arlington were the first to integrate Virginia’s public schools. The students were Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson.

All eyes were on these four. A 1957 attempt at integration in Little Rock, Arkansas — where Black students were confronted by a white mob and the National Guard and prevented from entering the school — was still fresh in people’s minds. As a preventive measure, one hundred police officers surrounded the school in Arlington in anticipation of violence. Television cameras were rolling.

But February 2, 1959, was later called by local newspapers “The Day that Nothing Happened,” and although no violence occurred, this event helped bring an end to the “Massive Resistance” movement in Virginia.

The Massive Resistance

In 1954, The U.S. The Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional in the landmark decision, Brown V. Board of Education. But Virginia public schools failed to desegregate. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed lawsuits, including one in Arlington, to challenge Virginia’s failure to end school segregation. In response, the Virginia General Assembly launched what was called the “Massive Resistance” in 1956.

If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.

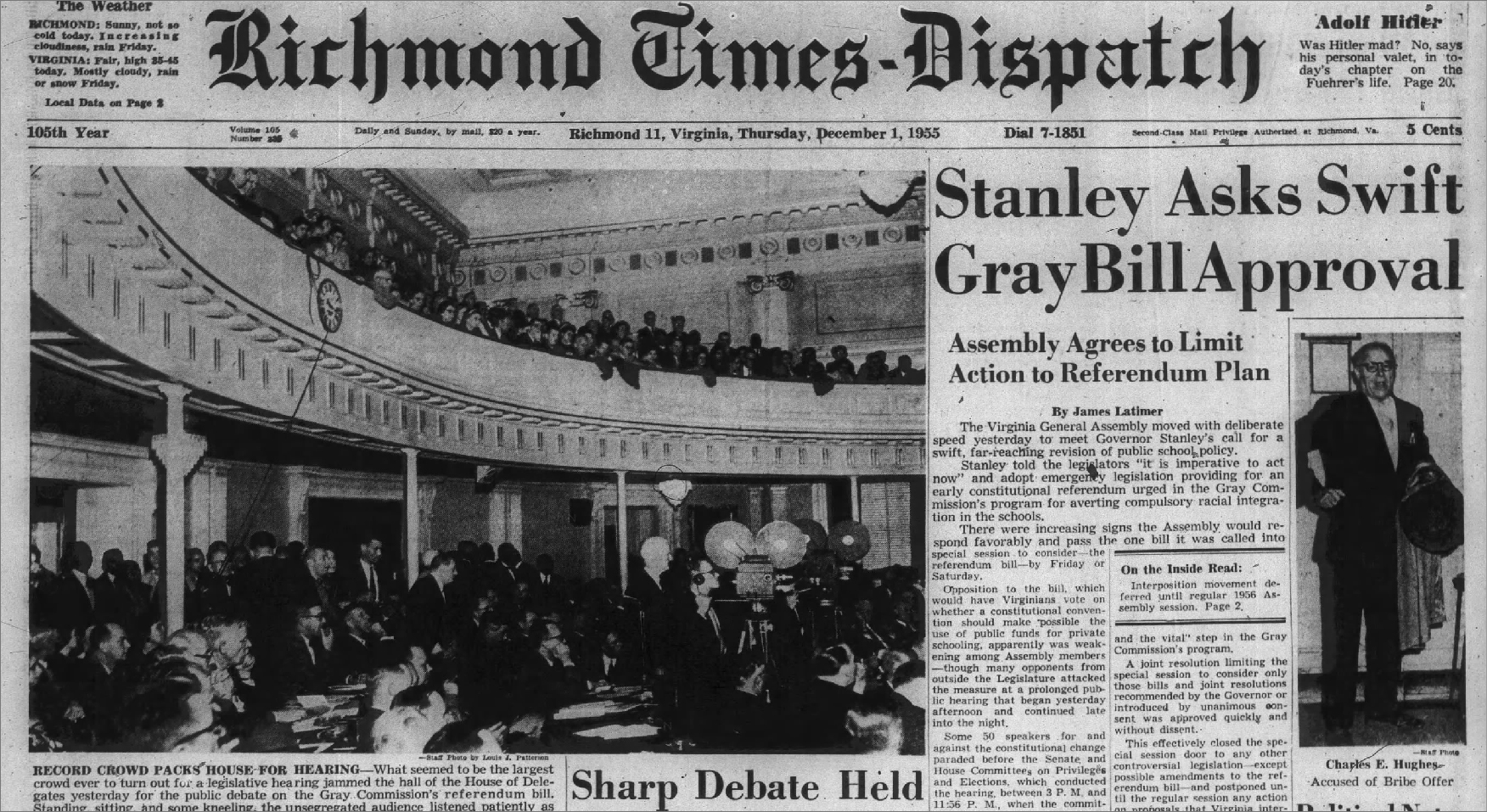

The movement was first advocated by U.S. Sen. Harry Byrd, the powerful Democratic senator representing Virginia. Byrd thought the Brown ruling was an unconstitutional attack on states’ rights and used his political power to block its enforcement. Virginia led other Southern states in the resistance. By 1956, Sen. Byrd convinced over 100 congressmen to sign the “The Southern Manifesto” in opposition to the Brown ruling. Virginia Governor Thomas Stanley followed suit and also took steps in defiance with a package of Massive Resistance legislation, which was dubbed the Stanley Plan.

The Stanley Plan legislation took several steps to keep schools from desegregating. Among these was empowering the governor to close any school facing a federal desegregation order, establishing the “Pupil Placement Board” to block the assignment of black students to white schools using racial criteria, and creating tuition grants for white parents who wanted to enroll their children in private schools.

The legislation was taken up by the state’s General Assembly and after hours of debate, with Confederate flags waving in the galleries, Virginia legislatures passed the Stanley Plan.

The Fight for Desegregation

This was not the first time Black students had arrived at the door of Stratford Jr. High School. Roughly a year and a half earlier, Leslie Hamm Jr., Joyce Marie Bailey, and George Tyrone Nelson were accompanied by Geraldine David, one of several white women who were active in the local NAACP. Upon entering the school, the group was immediately told to leave.

Leslie Hamm’s mother, Dorothy, recalled in an interview why she got involved with the desegregation movement and sent her child to Stratford, knowing that they would likely be turned away.

“My reason for doing that was because I felt that with the Supreme Court’s decision my two sons would have an opportunity to attend Stratford, an integrated school — and I told them the meaning of the Supreme Court’s decision, and I also told them that they would be going to Stratford. However, almost 2 years had passed, they still had not been permitted to attend; and this is why I really got involved.”

Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library · Oral History excerpt: Dorothy Hamm, recorded February 21, 1986

The Massive Resistance faced many legal battles, and the Virginia General Assembly did their best to dodge as many lawsuits as they could by exploiting loopholes in the court rulings. In September 1958, when federal courts ordered the desegregation of schools in Arlington and three other school systems in Virginia, Governor J. Lindsay Almond Jr. shut down the schools in Norfolk, Charlottesville, and Front Royal — sparing Arlington’s school — in order to keep the schools from desegregating.

wsbn40980, WSB-TV newsfilm clip of reporter Neal Strozier commenting on a public address by Virgina governor J. Lindsay Almond in Richmond, Virginia and on the recent integration of the previously all-white schools in Arlington County and Norfolk, Virginia, 1959 February 7, WSB-TV newsfilm collection, reel 0871, 42:09/44:25, Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection, The University of Georgia Libraries, Athens, Georgia

But after countless lawsuits and local activism by parents and local leaders, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that Arlington must admit four students who applied to attend segregated white schools in Arlington for the 1958–59 school year. Finally, in January 1959, both the Virginia Supreme Court and a federal court declared the Massive Resistance unconstitutional.

The Massive Resistance left a lasting impact on Virginia. Famously, the schools in Virginia’s Prince Edward County did not desegregate until 1964, and that required intervention by the U.S. Supreme Court. Unfortunately, decades later, a different form of segregation persists today, and it’s worsening. Decades of exclusionary practices in student placement and zoning, discriminatory housing policies, and exclusionary employment practices continue to maintain barriers to equitable and diverse learning environments for all.

References and Recommended Reading

“Project DAPS.” Arlington Public Library.

Shaver, Les. “Crossing The Divide.” Arlington Magazine, 2013. October 15.

“Oral History: The First Students to Desegregate Arlington Public Schools.” Arlington Public Library.

Hershman, James. “Massive Resistance.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities.

“Little Rock School Desegregation.” Stanford University.

Bestebreurtje, Lindsey. “Built by the People Themselves: African American Community Development in Arlington, Virginia, from the Civil War through Civil Rights”

Morris, James McGrath. “A Chink in the Armor: The Black-Led Struggle for School Desegregation in Arlington, Virginia, and the End of Massive Resistance.” Journal of Policy History 13 (3), 2001: 329–66. doi:10.1353/jph.2001.0009.

Smith, Douglas. “‘When Reason Collides with Prejudice’: Armistead Lloyd Boothe and the Politics of Desegregation in Virginia, 1948-1963.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 102 (1), 1994.

Mendes, Kathy, and Chris Duncombe. “Modern-Day School Segregation.” The Commonwealth Institute, 2020. November.