Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson spent most of his childhood living in an integrated neighborhood in Washington D.C. But during the summer, he stayed with his grandmother in Falls Church, where she owned a general store and a small farm. It was during these summers that Henderson saw the stark difference between life for Black people in the city and rural Virginia.

After attending Howard University and eventually Harvard, Henderson earned a Ph.D. in athletic training and became the first Black man to become certified to teach Physical Education in public schools. His first experience in fighting for civil rights was in the field of athletics and as a teacher in D.C. public schools, but he went on to become a local leader in Northern Virginia, as well as a national champion of civil rights.

Early Civil Rights Movements

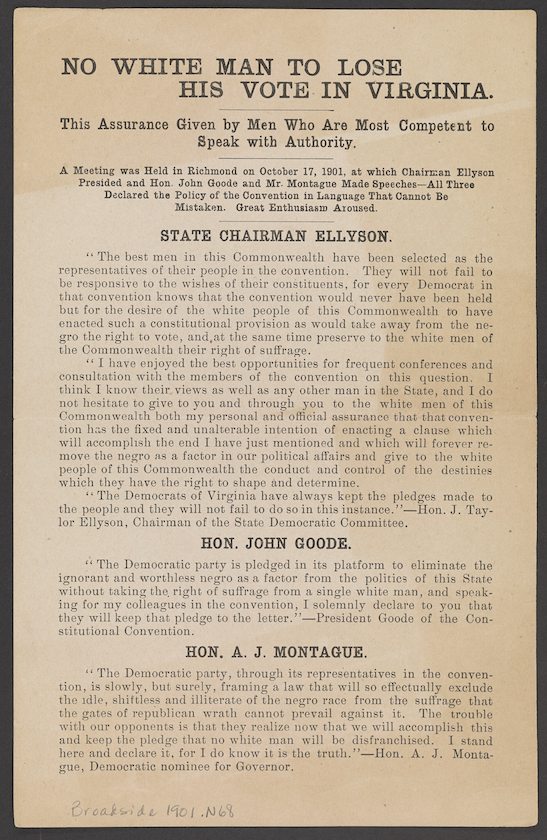

For the Black community, reconstruction brought temporary progress. Virginia’s legislature expanded voting rights and more Black men won elected office. At Virginia’s constitutional convention in 1867, 24 Black men were elected to serve with 80 white men. But resistance mounted; the statehouse began imposing poll taxes and literacy tests in the late 1800s and expanded voter suppression in the new 1902 state constitution.

We often associate the civil rights movement with the events of the 1950s and 1960s and historic figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., but the movement actually gained momentum decades earlier, thanks to activists like Dr. Henderson. From early in Henderson’s adult life, he was active in the civil rights movement. Between 1920 and 1960, he is said to have drafted more than 3,000 letters to the editor to protest discrimination. His letter-writing continued up until the day he died at the age of 93.

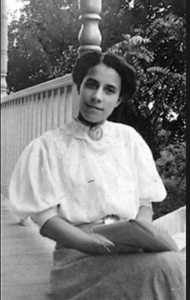

His wife, Mary Ellen Henderson, was also a local activist as well as a prominent educator in Northern Virginia. In 1919, the Black community requested that Mary Ellen help reopen Falls Church Colored School, the school for Black children that had been forced to close for lack of a teacher. Not only did she serve as principal, but she also taught grades four through seven in the two-room schoolhouse at . The overcrowded building lacked running water, heat, and indoor toilets.

Together, the Hendersons fought for a better school. In a study, titled “Our Disgrace and Shame: School Facilities for Negro Children in Fairfax County,” conducted by Mary Ellen and published in the 1940s, she drew attention to the racial gap in school resources for Black and white students. With help from her husband, who produced and distributeda flyer on the subject, the Hendersons and fellow activists were successful in convincing Fairfax County to build a new building for James E. Lee Elementary School, which included six rooms, as well as an auditorium, library, clinic, and cafeteria.

The Hendersons fought for civil liberties together, but it wasn’t easy. Their activism made the Henderson family targets of threatening phone calls, letters, and a burning cross on their front lawn.

Tinner Hill and The First Rural NAACP

At Tinner Hill in Falls Church, there stands today a stone archway that honors E.B. Henderson and his friend, Joseph Tinner, the son of the founders of Tinner Hill. Together, they advanced the cause of civil rights and in 1918 helped found the first rural branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), paving the way for NAACP rural branches across the South.

The branch was created in response to the threat of residential segregation in Falls Church. In 1912, Virginia authorized towns to establish “segregation districts,” making it legal for local governments to segregate neighborhoods. The U.S. Supreme Court had already cleared the way for local governments to do this. In Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, the Court ruled that segregation of public facilities was lawful as long as they were “separate but equal.”

In 1915, elected officials in Falls Church passed an ordinance that relocated Black residents to a small section of the town. Tinner and Henderson called a meeting of the Falls Church Colored Citizens Protective League (CCPL) and went on to file a lawsuit against the ordinance. With pressure, the ordinance was never enforced and was repealed in 1917. Soon after Tinner was elected the first president of the local NAACP branch.