When he was young, Stephen Hammond did not believe he was related to the family of George and Martha Washington. But when Hammond traced his genealogy back to the prominent Syphax family, whose earliest members were enslaved by the Washington family, he found out those stories were true.

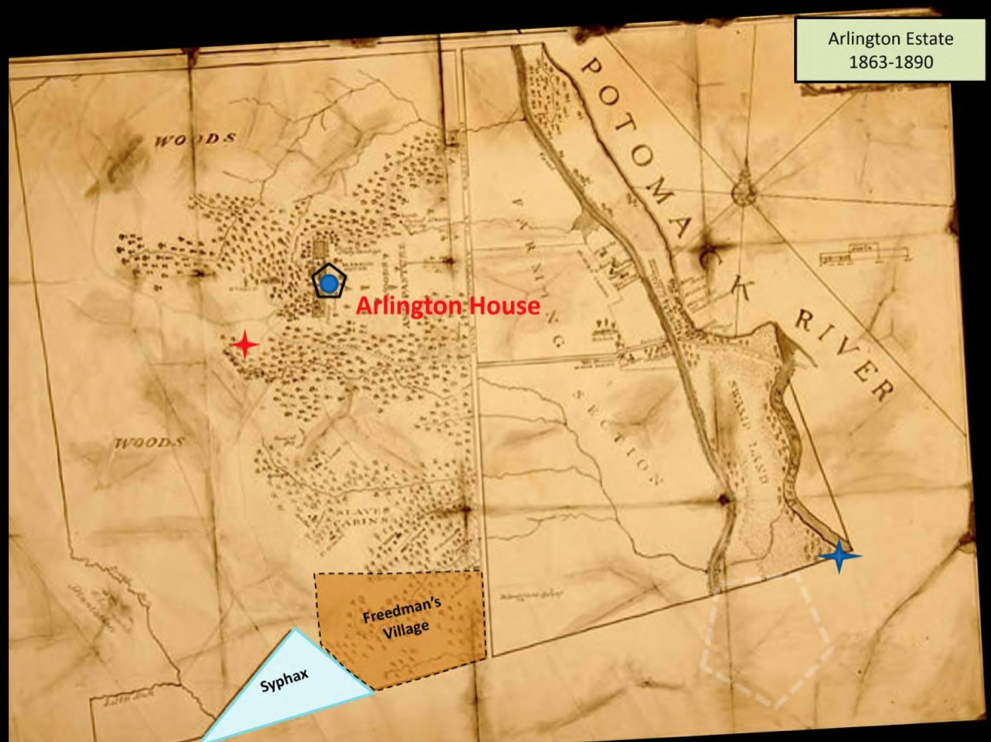

“We fully recognize that the first family of this country was much more than what it appeared on the surface,” Matthews Penrod, National Park Service ranger and programs manager at Arlington House, said at a ceremony recalling the marriage that occurred in 1821 in the parlor of Arlington House. The mansion belonged to George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington, and looked out on what was then his plantation and is now Arlington National Cemetery.

The wedding was unusual for its time; few enslaved people got married in the homes of their enslavers. But this time the bride was Maria Carter, a mixed-race woman and daughter of enslaved maid Arianna Carter and her enslaver, George Washington Park Custis. The groom was Charles Syphax, who had beenenslaved at Mount Vernon and was transferred, along with 57 other enslaved people, to Arlington House when Martha Washington died.

Ten years later, in 1831, another wedding occurred at Arlington House. On this occasion the bride was the daughter of George Washington Parke Custis and his white wife Mary Lee Fitzhugh, and the groom was a young U.S. Army officer named Robert E. Lee.

In 1826, after having two children, Custis sold Maria Syphax and her children, but not her husband Charles, to a Quaker in Alexandria. It is believed that he set Maria and her children free, as Quakers were against slavery and often purchased enslaved individuals to free them. Soon after gaining her freedom, Maria acquired 17 acres of land on the southwest portion of Custis’ property.

Maria and Charles had eight more children, all born free since a child’s status was dependent on his or her mother. But Charles remained enslaved until 1862.

Freedman’s Village

At the start of the Civil War, Robert E. Lee’s wife had her land and Arlington House confiscated when she failed to pay taxes in personto help support the war effort. The preciousland that Maria Syphax had acquired on the edge of the property was also confiscated because they had no proof of ownership.

Mary and Charles wereconsidered squatters until the oldest son, William, who was then working atthe U.S. Department of the Interior, petitionedCongress to help bring a bill to the floor that would returnthe property to his mother. The bill, “An Act for the Relief of Maria Syphax”, was passed by Congress and signed by President Andrew Johnson.

The Custis property eventually became part of Freedman’s Village, a contraband camp that the federal government established for those who were freed, or escaped slavery. Maria and her family were involved with activities at the Village, including teaching skills such as sewing and advocating on behalf of individuals to petition the government for assistance.

When the federal government tried to close Freeman’s Village in the late 1880s, Maria’s son, John Syphax, acted as a representative for the community. He argued that the residents had paid rents, constructed the houses, and held a valid claim to the land. He noted the construction of Mount Olive Church, around which several houses were built. Should the residents not be allowed to stay in Freedman’s Village, John Syphax argued that they must be compensated for their homes and improvements.

The government agreed to the payments and a survey was conducted to assess the property. Most residents received some sort of compensation for their land, but the payments were well below market value. Ultimately, each household received an average of $103, much less than what Syphax requested. The Village was finally closed in 1900.

A Family Legacy

Maria Syphax died in 1886, leaving the land to her surviving children. The family grew and dispersed throughout Northern Virginia and the surrounding areas. In 1944, the 17-acre plot that belonged to Maria was condemned, and the remaining members of the Syphax family wereexpelled, and the property was given to Congress. The family remains very active today in Northern Virginia,

The Syphax story illustrates the resilience of many Black families in Northern Virginia, who escaped enslavement and seized the opportunity to acquire land, find jobs, start businesses, and create a better future for their children. Within the space of one generation, a formerly enslaved maid saw her sons become government officials. Syphax descendants have carried on this legacy; they have served in the military, attended and taught at Howard University and other prestigious universities, been elected to hold office, and advocated for social justice reform.