Northern Virginia is known for its affluence. Loudoun County, for example, currently boasts the highest median household income of any county in the United States.

Much of that affluence dates to the 1600s.

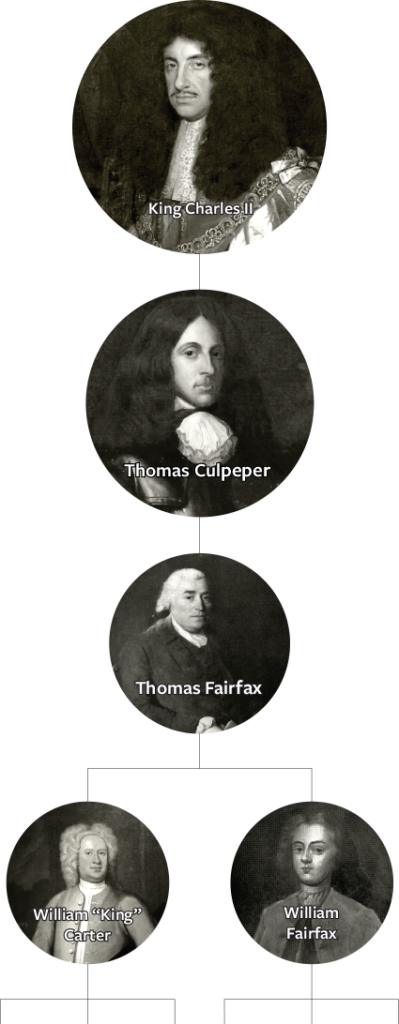

In 1649, King Charles II rewarded his supporters with land grants from what was called the Northern Neck Proprietary—a massive area of land stretching between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers and extending west to the Blue Ridge mountains.

Much of this land was bought up by Thomas Culpeper, governor of Virginia, and inherited by his son-in-law, Thomas Fairfax (1693-1781). Fairfax, living in England, appointed land agents to manage his property, such as Robert “King” Carter (1662-1732), who acquired 300,000 acres and became the richest man in Virginia. Fairfax is said to have been furious when he learned, from Carter’s obituary, that he had used his role as a land agent to amass wealth, and appointed his cousin, William Fairfax (1691–1757), to take over the role. William built and lived at the Belvoir plantation, located where the U.S. Army base, Fort Belvoir, now stands.

Much of the affluence of these 17th century land barons can still be felt in the area today, and these men used their power to set up structures that would maintain wealth and power for generations. White merchants, plantation owners, and politicians–serving in local government or in the legislature or governor’s mansion in Richmond–went to great lengths to secure their advantages: the systems, institutional structures, and policies they adopted helped them grow their wealth, retain power, and cloister themselves in white communities. Many of these policies were also designed to keep people of color from entering their neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces.

What is Generational Wealth?

Today’s priciest Northern Virginia properties can be traced to this “landed gentry.”

For example, the census tracts in Loudoun County where the Carter family once lived today have the county’s highest median household income ($239,250 per year). The wealthiest land in Northern Virginia, tracts in Great Falls and McLean where incomes average $250,000 per year, were once the plantations of William Fairfax’s son, Bryan, and the land magnate Thomas Lee (1690-1750). Lee, for whom Leesburg is named, owned roughly 25,000 acres of today’s Arlington County, Fairfax County, Prince William County, and Loudoun County.

White families in high-income areas of Northern Virginia have benefited to varying degrees from inherited wealth. Although some people of high socioeconomic status worked their way up from poverty, a large number of successful white families benefited from the property ownership, education, savings, promotions, and other systemic advantages that societal structures offered their parents and prior generations.

Today’s Belmont Country Club, located in Ashburn just off of Route 7, was once the Belmont plantation of Ludwell Lee, the grandson of land magnate Thomas Lee. Upscale areas of Chantilly were part of the Sully estate of Lee’s nephew, Richard Bland Lee. John Washington (1631-1677) bought the riverfront land that became the Mount Vernon estate of his great-grandson, George, and today’s Fort Hunt, where median household income now approaches $220,000 per year. Exclusive areas of southern Fairfax County were part of the largest property of its time: the 24,000-acre Ravensworth plantation of George Washington’s friend, William Fitzhugh (1741-1809).

But many Black people of the same era were systematically denied these resources for upward mobility. Lacking the transgenerational transfer of wealth that occurred in successful white families, Black people in Northern Virginia were often at an economic disadvantage before they were even born. The widening of the Black-white wealth gap that occurred after World War II was less about determination, resilience, and hard work — which existed in all racial groups — than the structural conditions set by society, often rooted in systemic racism, and the insidious ways wealth inequality was allowed to compound over time.

The same insidious process continues today and perpetuates the massive wealth gap we see among people of color. Systemic inequities and generations of poverty continue to make it difficult for Black Americans to generate wealth. The historic practices of redlining, mass incarceration of Black people, and other exclusionary policies, systematically prevented people from building wealth and thereby weakened the financial security of their descendants today. Hundreds of years of inequity have left their mark; for example, earning a college degree, a foundation for higher earnings in today’s economy, confers less benefit to Black graduates than to their white counterparts. A 2018 study states that “among college-educated black families, about 13 percent get an inheritance of more than $10,000, as opposed to about 41 percent of white, college-educated families.” Additionally, about 16 percent of those white families receive more than one such inheritance, versus just two percent of Black families. On average, whites families inherit more than $150,000, whereas the average inheritance in Black families is less than $40,000.

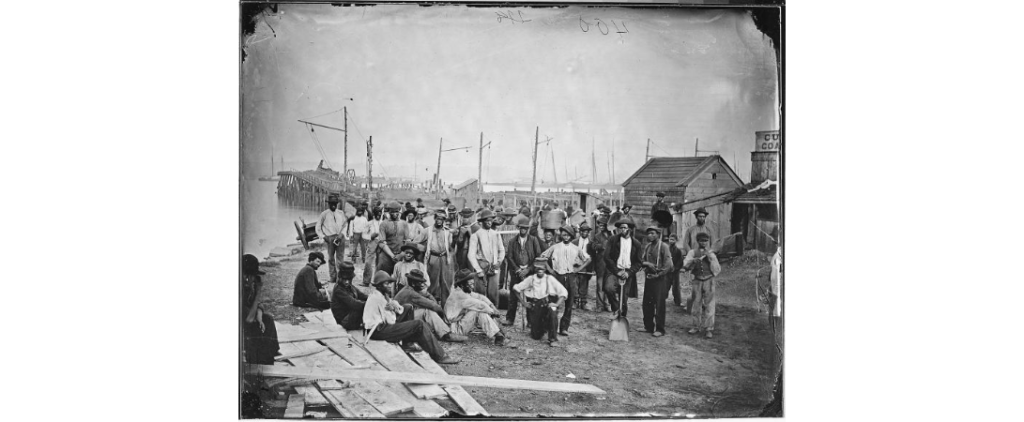

Dozens of tobacco plantations stretched across Northern Virginia, from outer Loudoun County and Prince William County to the riverfront where Reagan National Airport is now located. The ports of Alexandria and Dumfries were busy exporting tobacco. While enslaved people rolled hogsheads of tobacco from the plantations down “rolling roads” to the port, their owners were using their wealth and social standing to build political power.

Learning from History

Northern Virginia is home to government officials, military officers, defense contractors, and social elites. However, the prestige and affluence of the region mask deep inequities—the pockets of extreme disadvantage that exist in the midst of the wealth.

Calls to help such communities and reduce inequities often encounter resistance, sometimes for fiscal reasons but also because many—consciously or not—view “bad neighborhoods” as undeserving and responsible for their troubles. This narrative blames the marginalized for what they do to themselves rather than what was done to them. It feeds off an ignorance of history and of the resilience and determination of people of color to create a better future for their children. To to believe that struggling neighborhoods were never vibrant and that people of color are, and have always been, is to ignore the facts.

History provides a clear record of people struggling to succeed and of a concerted effort by those in power to block their efforts. The “islands of disadvantage” on today’s maps did not arise by chance; they are the product of policies of exclusion and segregation, carried out over generations, that kept people of color “in their place,” choked off economic resources on which communities depended, and set them into an inevitable downhill spiral.