In 2016, Chris Fullman closed on his house in Richmond’s Lakeside. After signing the papers, his closing attorney handed over a copy of the covenants and one of the items caught him by surprise.

Fullman told Virginia Public Radio, “the second item on the list was basically, if you’re not white, you can’t live, rent, or do anything on this land unless you work for the property owner.”

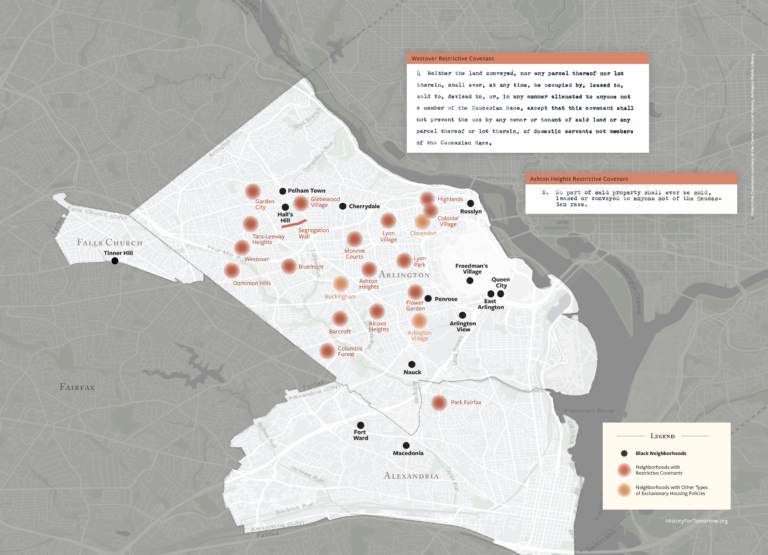

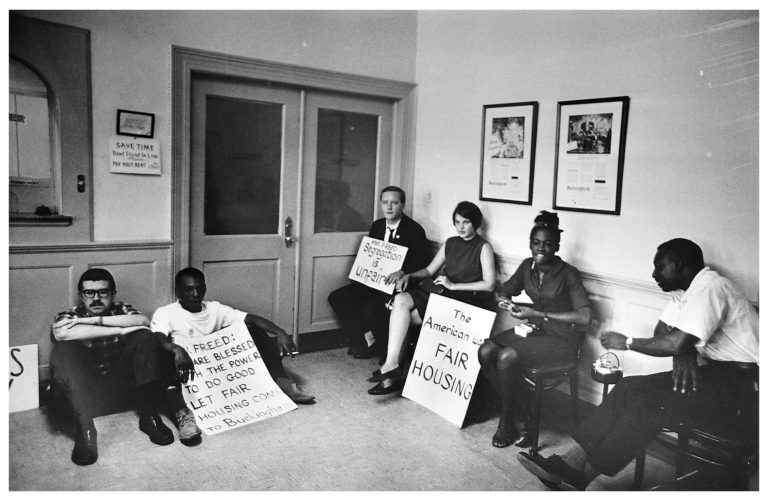

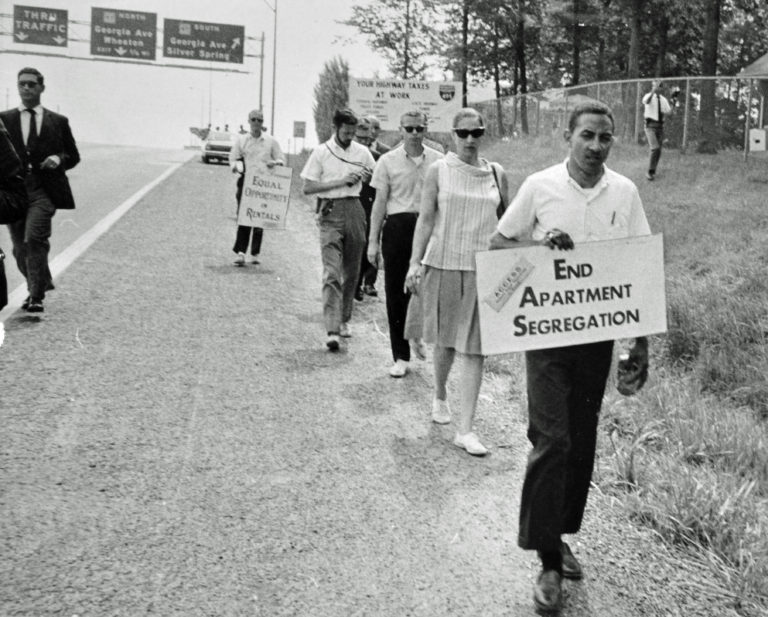

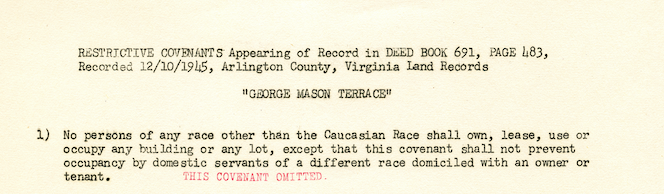

They are known as restrictive covenants and they are still on the books, not only in Richmond but throughout the nation–and they have a history in Northern Virginia. Some are a century old and have clauses that specifically ban owners who are “non-Caucasians.” A homeowner in Licolnia, near the old Landmark Mall in Alexandria, recently wrote about his shock when he discovered a restrictive on an old deed on his house, reflecting on how his neighborhood would look if those types of covenants were still enforced. Enforcement of restrictivecovenants was made illegal by the 1968 Fair Housing Act. But many stayed on the books. In 2020, the Virginia general assembly passed House Bill 788 which prohibits a deed containing a restrictive covenant from being recorded and provided the language for a Certificate of Release of Certain Prohibited Covenants to be recorded to remove any such restrictive covenant.

“Only the Caucasian Race”: Restrictive Covenants and Exclusionary Policies

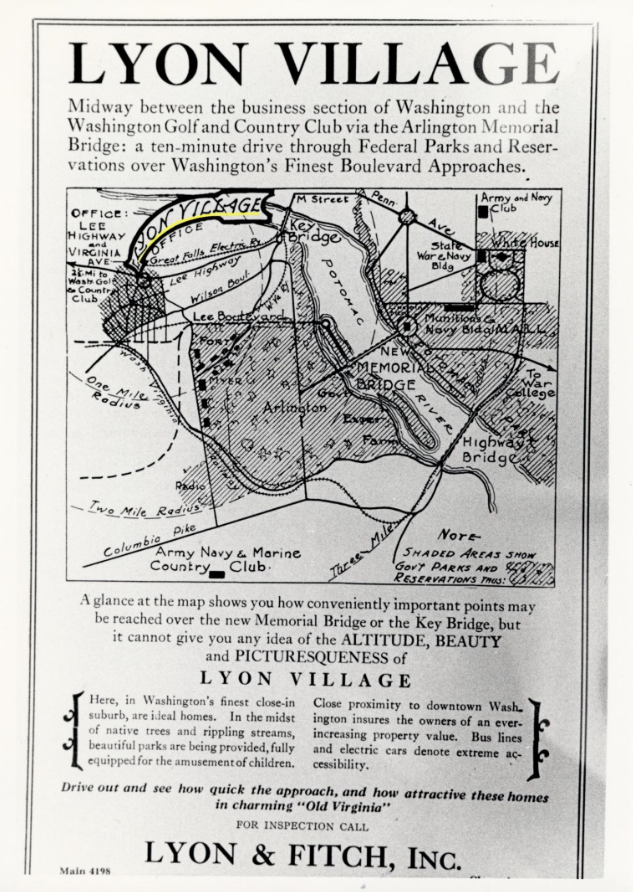

< Ad for Lyon Village. Founded by Frank Lyon in 1923, Lyon Village featured strict building restrictions for look and size of houses. The community was also segregated for whites only and the homes contained restrictive covenants that block minorities until the mid-20th century. Source: Center for Local History.

In 1912, Virginia authorized “segregation districts,” making it legal for local governments to segregate neighborhoods, an action taken by the city of Falls Church in 1915. When the U.S. Supreme Court banned such ordinances in 1917, white communities in Arlington County and Fairfax County enacted restrictive covenants that prohibited sales to “non-Caucasian” buyers.

These racially restrictive covenants, as well as exclusionary zoning, urban renewal, and discriminatory loan policies have all been used to restrict and attempt to push out Northern Virginia’s Black population.

Many of these areas can still be recognized today. For example, Lyon Park’s restrictive covenant stated, “neither said property nor any part thereof nor any interest therein shall be sold or leased to any one not of the Caucasian race.” Alcova Heights covenants stated that “no portion of said land shall be sold or leased to anyone of African descent.”

While some areas like Barcroft did not feature restrictive covenants in their community’s home sales, African Americans were kept out through unofficial channels of mutual understanding. Bylaws for the Barcroft School and Civic League formally articulated this exclusion, stating that membership was only available to residents “who are members of the Caucasian race.”

But not all exclusionary housing was so obvious; more covertypractices to keep Black people out of Northern Virginia’s white neighborhoods were practiced not only by local governments but also by developers, realtors, banks, and white families themselves. And still today, years of policies, created in attempts to find loopholes in laws that banned racist practices, have kept Black families out of certain communities.

Redlining and Other Practices of Housing Discrimination

When President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Housing Act of 1934, the government established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which later popularized the practice of ‘redlining,’ in which maps produced for lending institutions discouraged loans to buyers in predominantly Black neighborhoods (designated by red shading). This practice, which preferentially insured mortgages for homes in majority-white neighborhoods, served not only to segregate people of color but also to prevent Black families from buying property, building savings, and passing wealth to their children. .

Redlining is one of the most visual examples of how the history of exclusion in the United States still holds a grip on the health of today’s communities. Redling maps from the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) correspond closely with current maps of poverty, low life expectancy, food deserts, and other examples of the ill effects of chronic marginalization.

Some white communities, set on preventing Black families from entering their neighborhoods, even took matters into their own hands. For example, a “segregation wall” was built in segments from North Edison Street to North Glebe Road in Arlington to separate the neighborhoods of Hall’s Hill/High View Park and Waycroft-Woodlawn. The wall was later described by Arlington County officials as “a patchwork barrier of fencing and brick or cinder-block segments that has separated the [Black and white] neighborhoods for years.”

Although only remnants of the wall still stand today, people of color in Northern Virginia continue to face discrimination in home buying and homeownership, as when realtors steer prospective buyers from some neighborhoods and when climbing housing costs price people of color out of the housing market. Such practices and small microaggressions serve as a “not welcome” sign to Black buyers.

Virginia has convened a commission to look at these past policies, hence the recent law that made removing restrictive covenants easier, but much needs to be done to undo the damage that many of these laws caused.