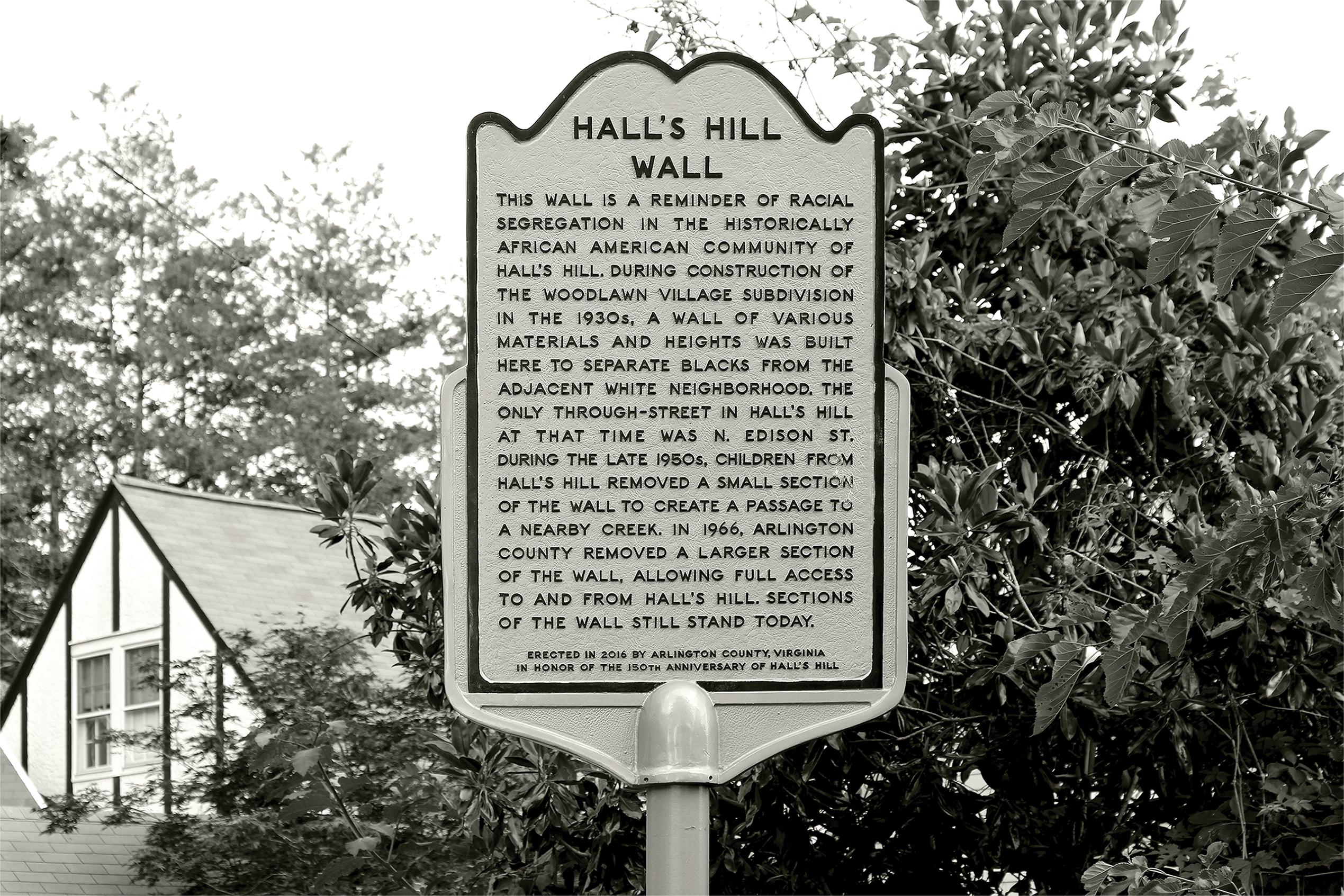

In the 1800s, formerly enslaved Black families in Northern Virginia were eager to buy land, build houses, and open businesses. They built dozens of enclaves, stretching from western Prince William County to the Alexandria waterfront. However, when the turn of the 20th century brought expanded railroad, trolley, and road service from D.C. into Northern Virginia and heightened demand for suburban housing, developers and politicians aggressively sought land belonging to Black families. Zoning policies, discriminatory lending practices that prevented Black buyers from obtaining mortgages, pricing pressures, and physical threats uprooted Black families, prevented them from buying property in more affluent white areas, and segregated the Black population into smaller and smaller enclaves. Decades after paved roads eased access to white subdivisions, Black communities were still served by dirt roads and went without municipal services such as sewage, water, and street lights. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was common for residents of Black enclaves like Hall’s Hill to place lanterns in their windows to light the streets at night.

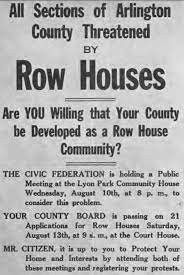

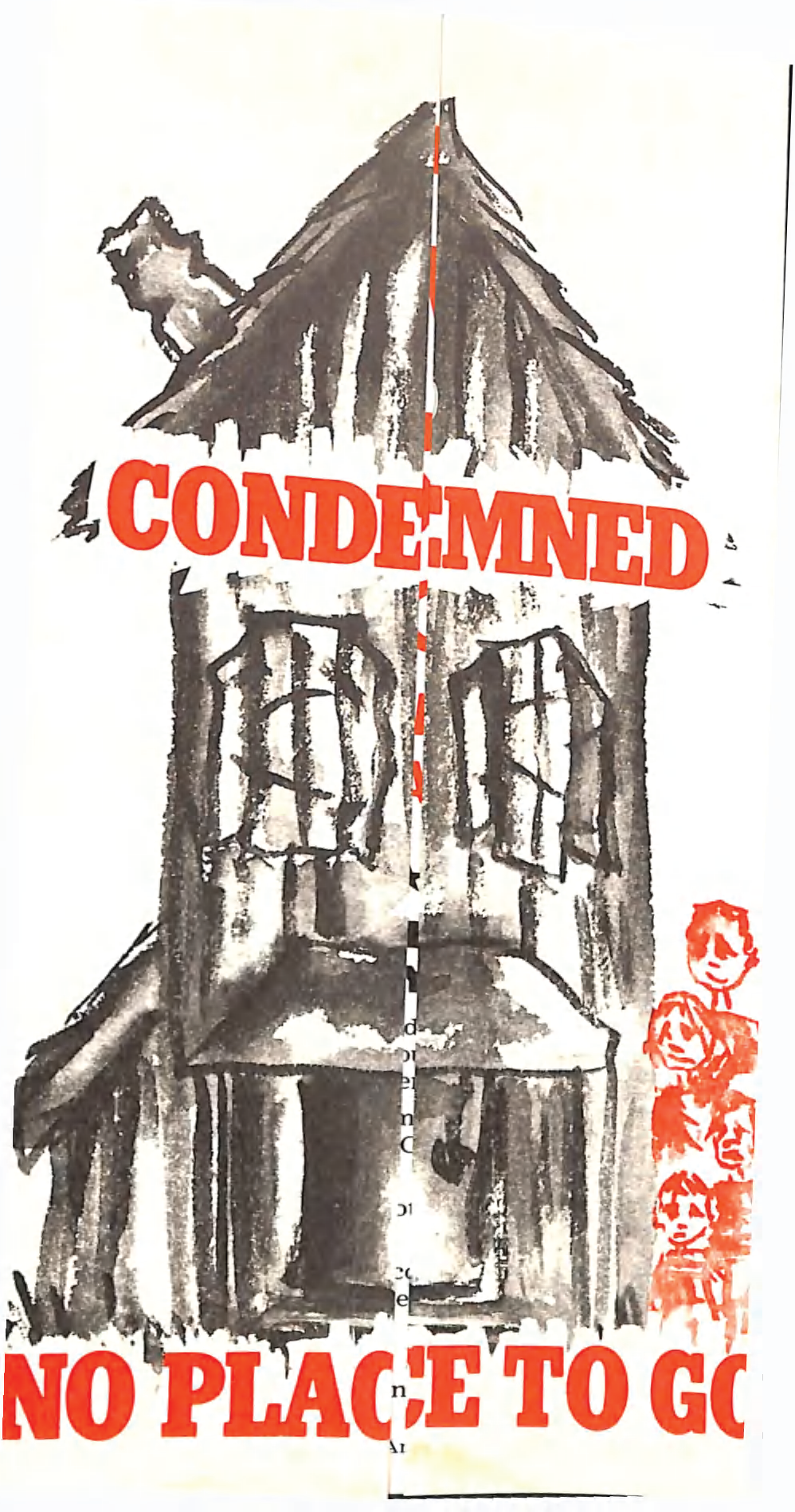

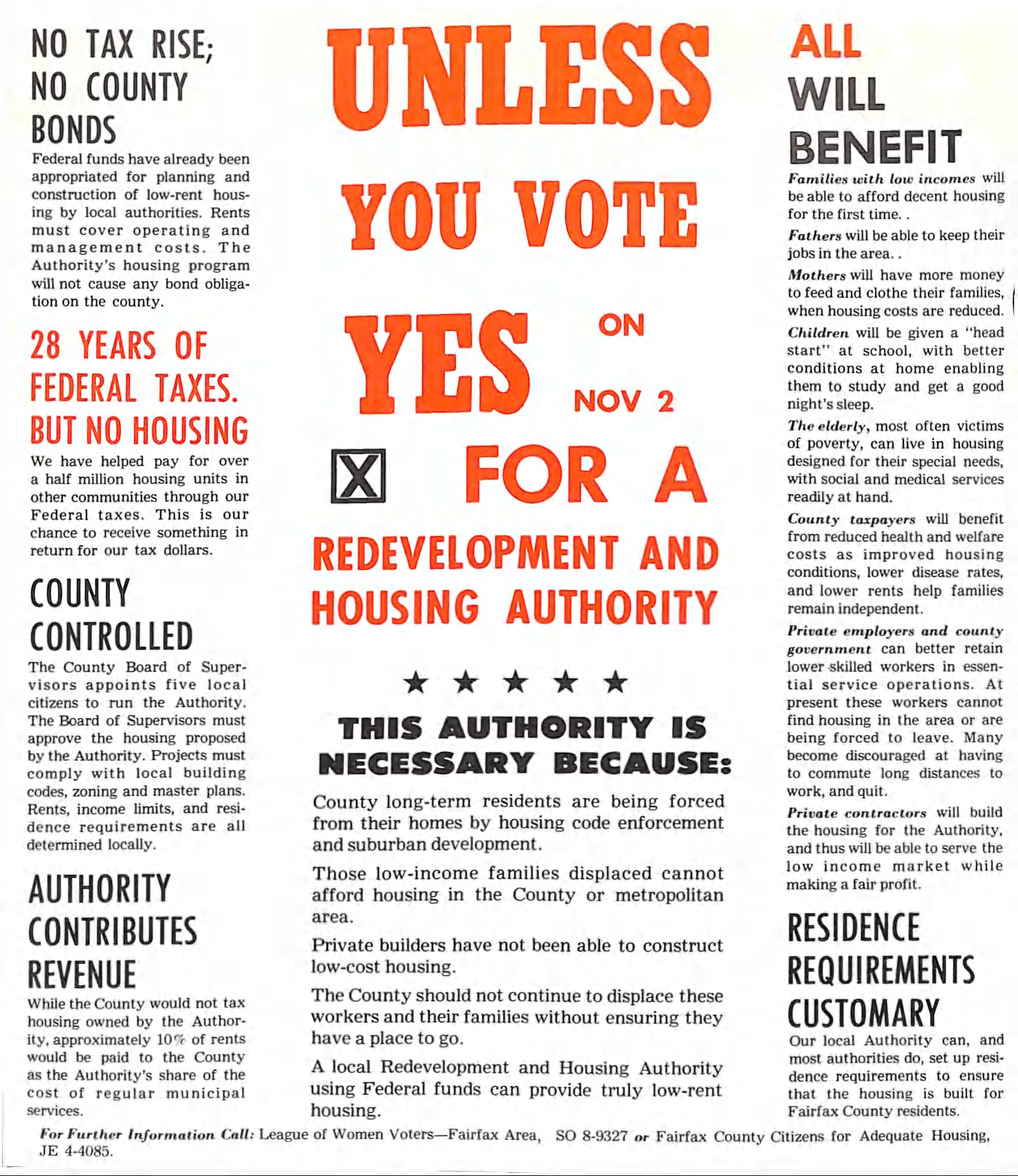

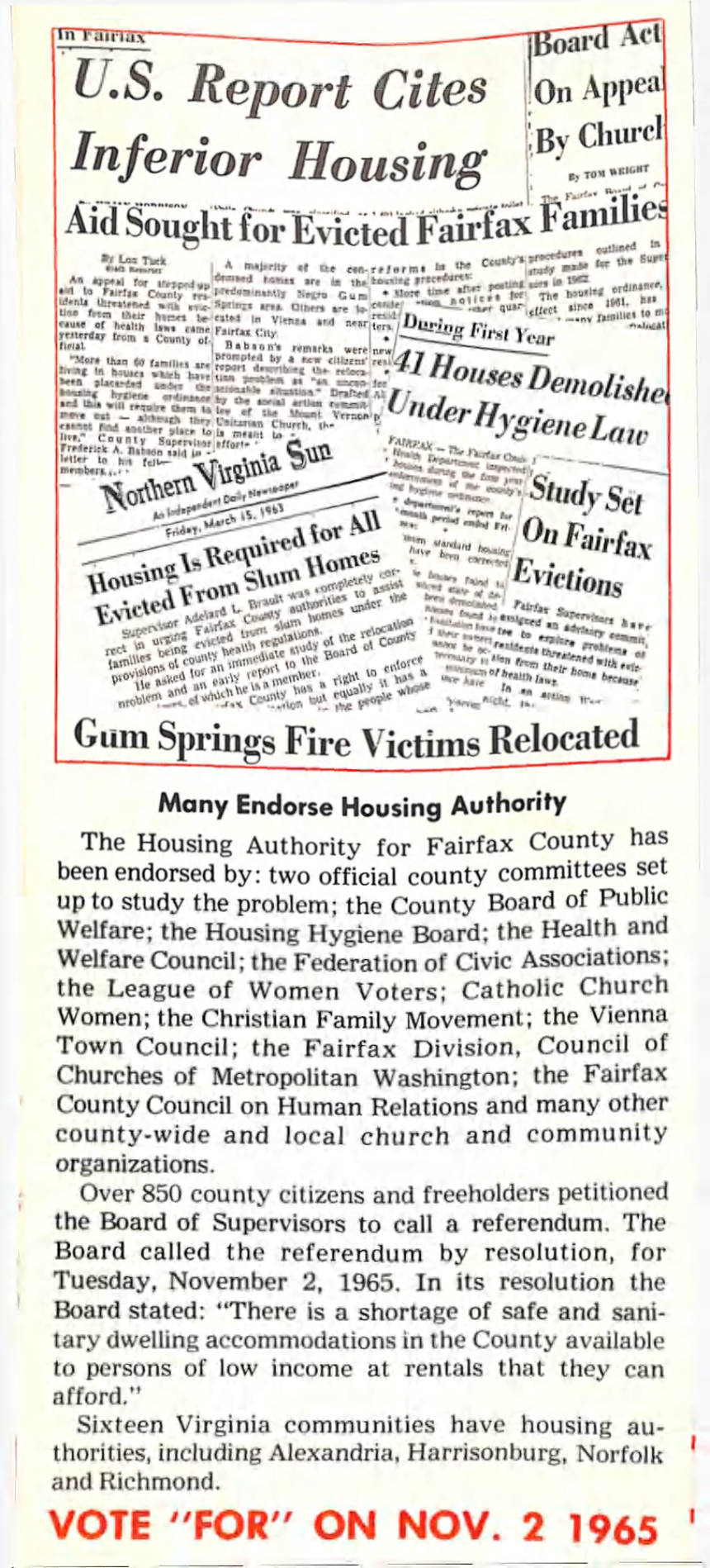

Black homeowners with limited educational opportunities, few job options, and depreciating property values often lacked the finances to modernize their homes. Federally subsidized mortgages that became available in the 1930s were approved almost exclusively for white buyers and routinely denied to Black buyers, especially those seeking homes outside of “redlined” areas. The disinvestment and resulting housing decay in Black neighborhoods played into the hands of developers and politicians, who rebranded Black enclaves as “blight,” cited violations of housing codes, and authorized developers to clear Black properties for new construction. By World War II, suburban development, restrictive covenants, and discriminatory lending had pushed Arlington’s once widely dispersed Black population into three small enclaves, and the 19th-century Black communities that once dotted Fairfax County and Loudoun County were gone.

Fast Forward

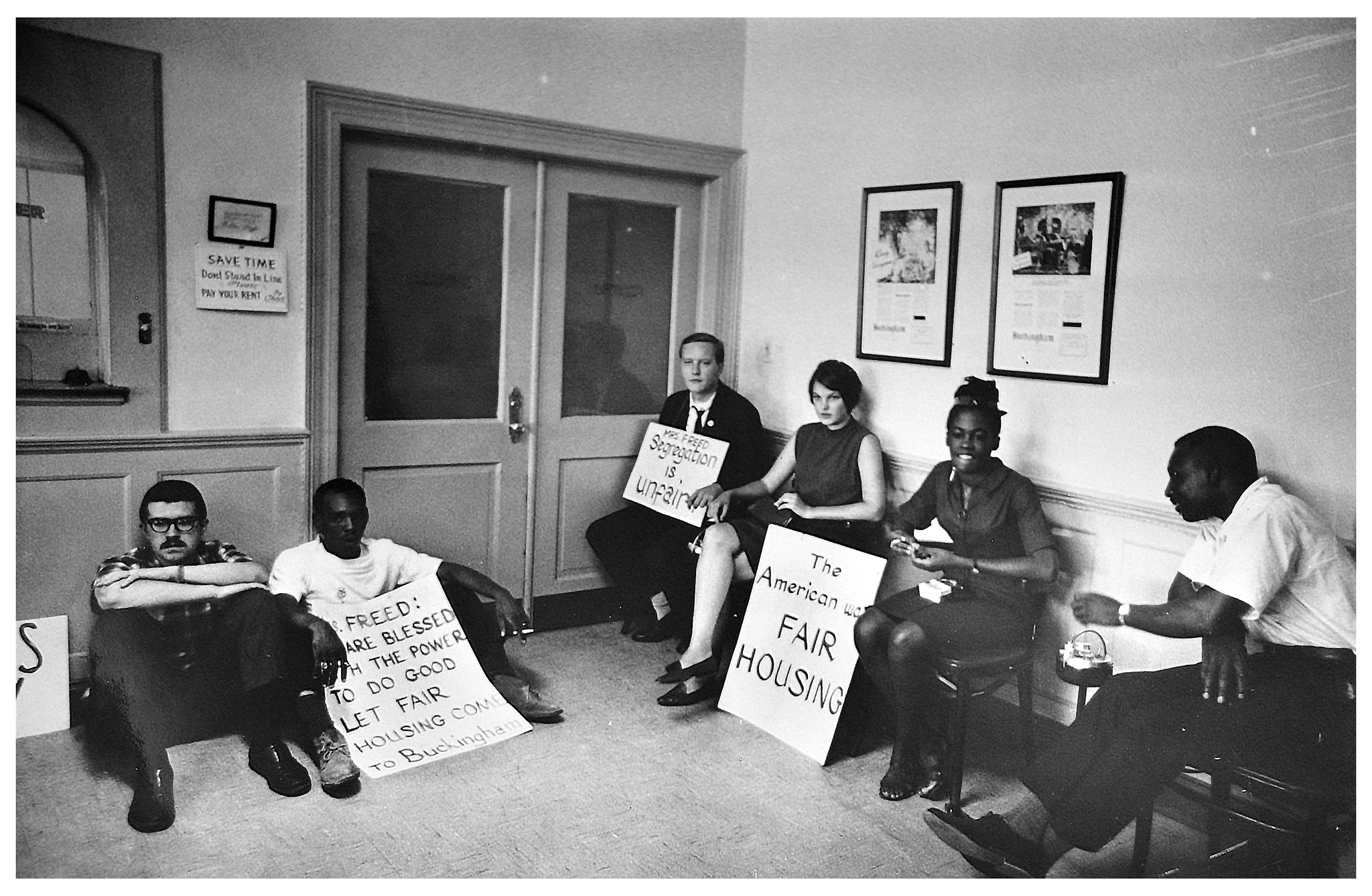

Although the Fair Housing Act of 1968 brought major reforms limiting housing discrimination based on race, the practice did not disappear and has, instead, evolved into what exists today. As of 2017, prospective Black homeowners were denied mortgages at a rate 80% higher than that of white applicants. The gap between Black and white homeowners is even wider today than it was in 1960. Although gains in Black homeownership rates were made in the decades after the Fair Housing Act, they were erased in the 21st century. Black people were more vulnerable than whites to predatory lending, were more likely to fall victim to the 2008 housing market crash, and benefited less from the economic recovery that followed the Great Recession.

Policies to reduce racial inequities in wealth distribution and property ownership in Northern Virginia are a recognized priority of state and local governments. For example, in 2020 a Governor’s commission recommended imposing state limits on exclusionary zoning in localities and adopting more effective inclusionary zoning and increasing allocations to the Virginia Housing Trust Fund, which provides low-interest loans for housing projects. Local jurisdictions and the private sector—including developers and investors—must pursue efforts to broaden access to housing that is affordable, including promoting the development of mixed-income neighborhoods and limiting requirements for single-family, detached homes. In 2019, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments set worthy targets for the optimal amount, location, and cost of new housing units, which local governments should embrace. Land banks, which exist elsewhere in the Commonwealth, can transform vacant, abandoned property into productive use. And the financial sector can help by expanding access to full-service banking in communities of color and abolishing discriminatory and predatory lending practices.

Stories

Dig deeper into the topics by exploring the stories of the past that have shaped the present.

Eminent Domain and the Displacement of Black Communities

Eminent Domain and the Displacement of Black Communities More than a century ago, before there was today’s Prince William Forest Park, there was a community

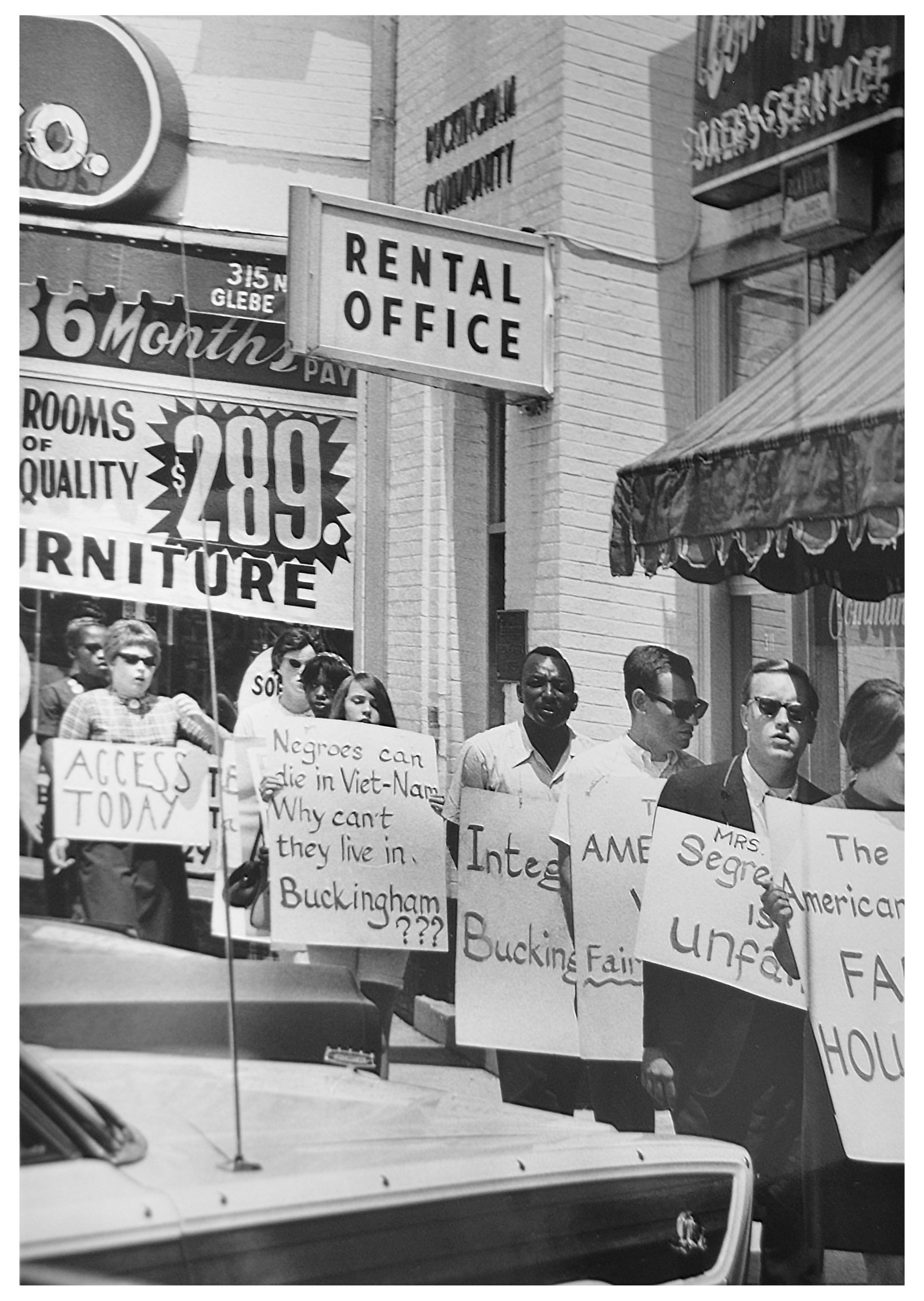

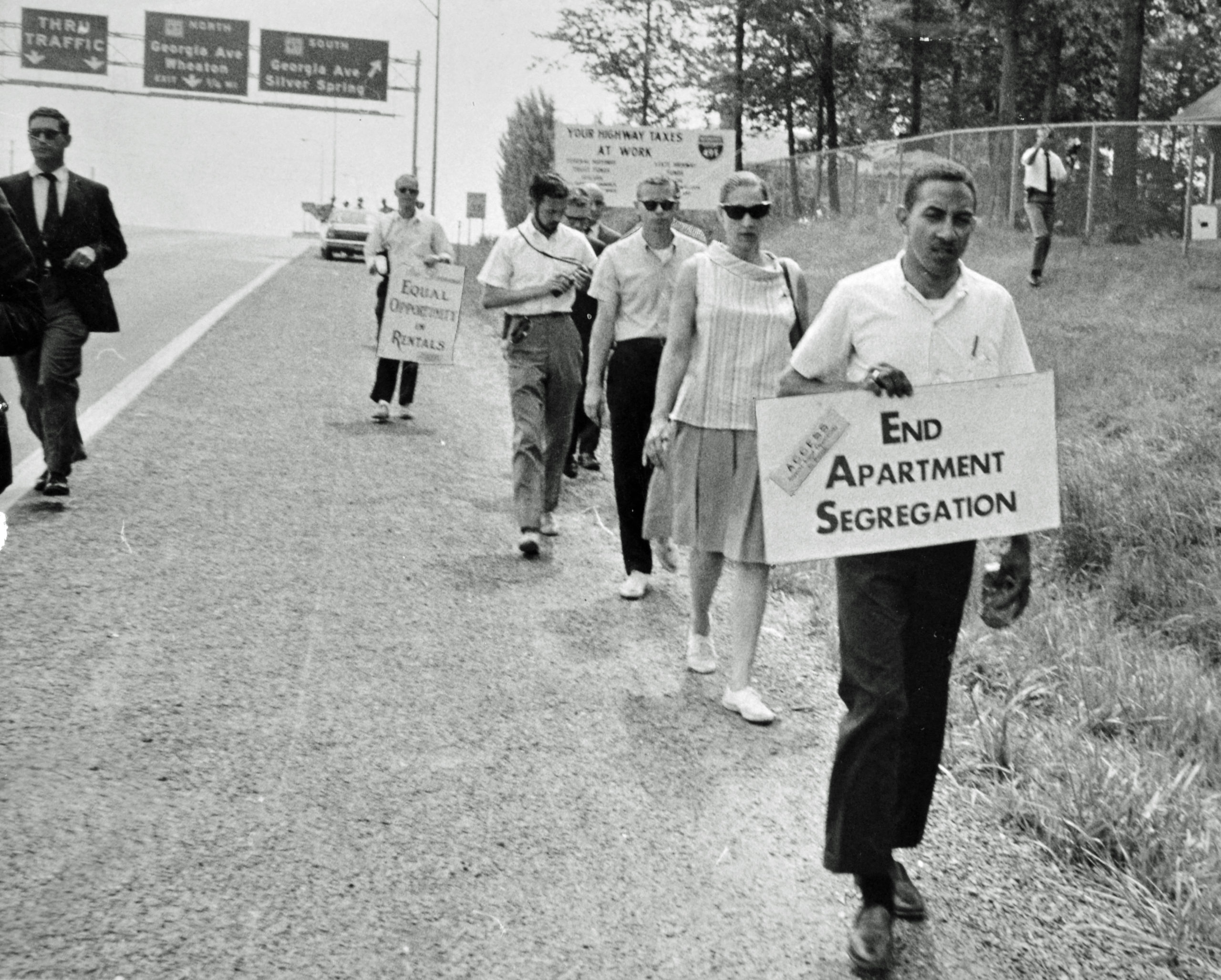

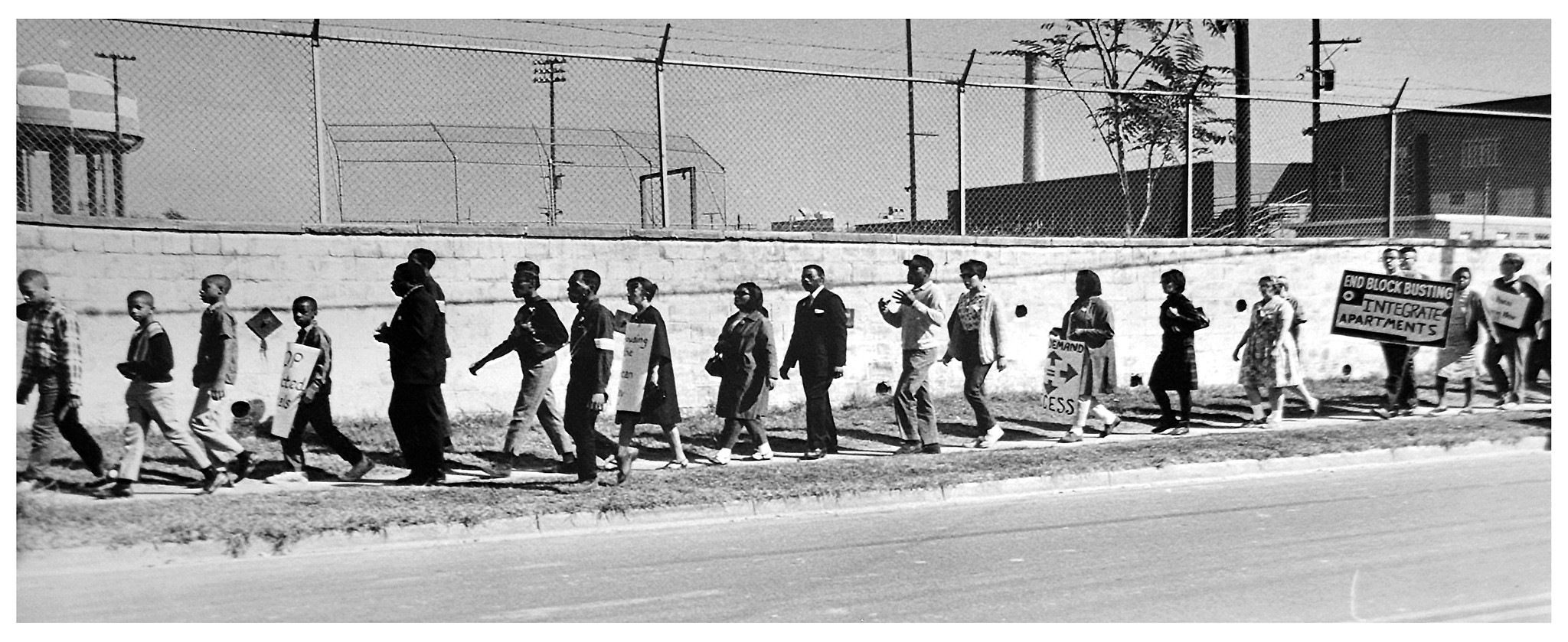

Housing Segregation: Nowhere to Live

In 2016, Chris Fullman closed on his house in Richmond’s Lakeside. After signing the papers, his closing attorney handed over a copy of the covenants