The Black experience in Northern Virginia began without freedoms. Africans first arrived in the 1600s as chattel (property), and the enslaved population grew in numbers in the 18th century. Although late 18th century Virginia allowed some enslaved people to gain their freedom, lawmakers tightened their grip in the early 1800s, passing laws to re-enslave free Black people if they did not leave the Commonwealth and prohibiting Black people, free or enslaved, from congregating. Northern Virginia became a center of the domestic slave trade, shipping enslaved Black people from the port of Alexandria to Southern destinations.

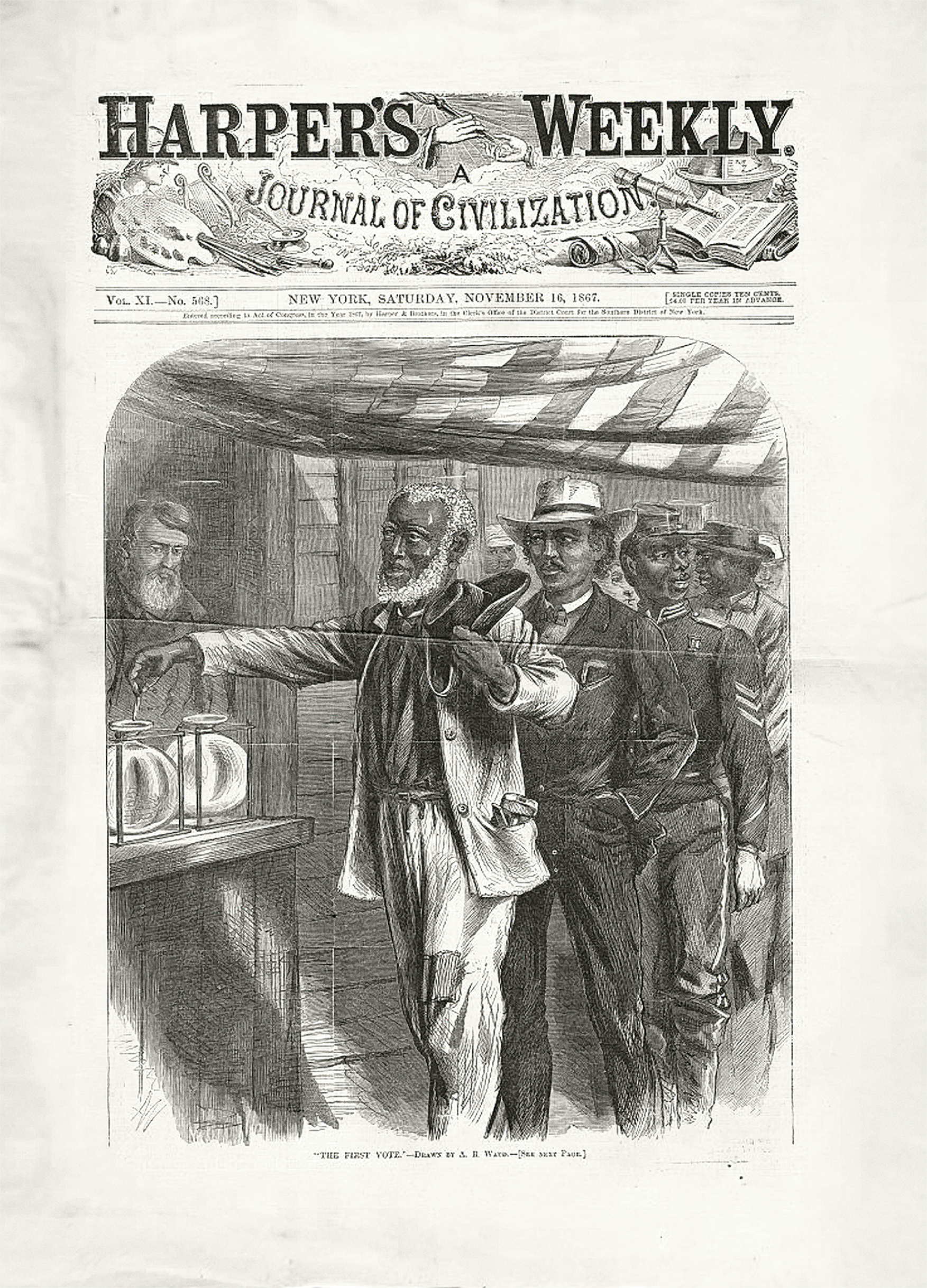

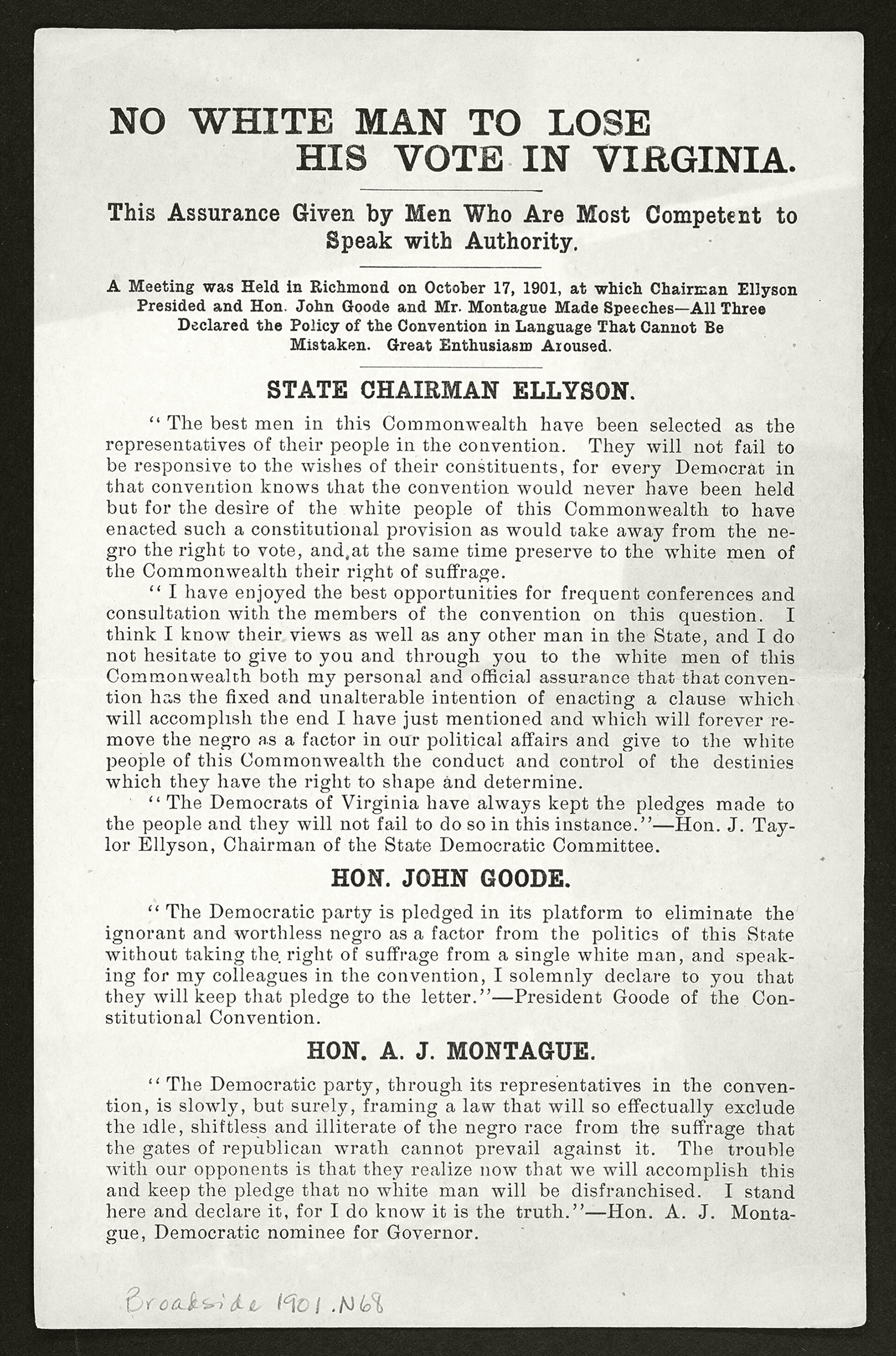

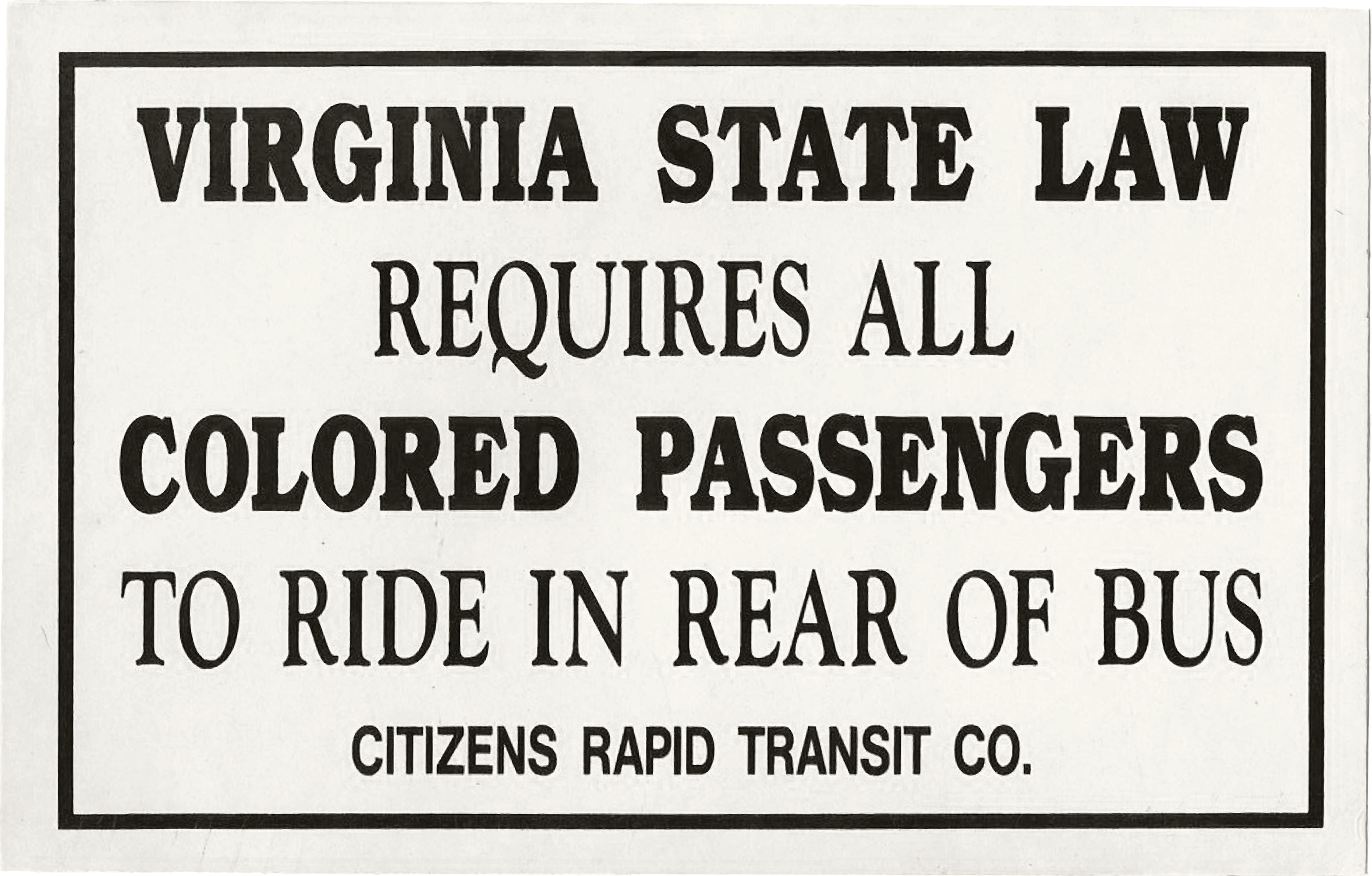

By the start of the Civil War, Virginia had the largest enslaved population of any Confederate state. Although the 1860s brought an end to chattel slavery and early Reconstruction expanded civil rights, the ensuing backlash of Jim Crow laws and practices terrorized Black families and quashed social, economic, and political rights. In Northern Virginia, those laws and practices affected every aspect of life. Black passengers were beaten on trolley cars for the slightest infractions, the Ku Klux Klan was active, and public lynchings occurred in Leesburg and Alexandria from the late 1870s into the early 20th century.

Fast Forward

Freedom of movement is not fully possible when the innocent activities of daily life—from driving a car to entering a store, especially in mostly white areas—induce suspicion, microaggressions, and perceived threats to the physical safety of Black people. The chronic stress this induces among victims of discrimination has known harmful effects on physical and mental health. Too often, Black people face threats from law enforcement itself.

Leaders in Northern Virginia should ensure that all residents have a voice and can participate in decision-making and leadership. Initiatives aimed at improving the safety of people of color in Northern Virginia are urgent. No group should be victims of hate crimes and violence. Particular priorities are addressing systemic racism in law enforcement and criminal justice to eliminate racial bias in apprehension, conviction, sentencing, and incarceration. All law enforcement agencies in Northern Virginia should accelerate efforts to address implicit bias, eliminate police misconduct, and aggressively prosecute hate crimes. Some efforts are already underway. For example, in 2015, Fairfax County created an independent Police Civilian Review Panel and Independent Police Auditor, initiated a body camera program, and launched Diversion First, a program that offers alternatives to incarceration for people with mental illness, developmental disabilities or substance use disorders. Sentencing reforms are also necessary, including those recommended in 2020 by Governor Northam’s Commission to Examine Racial Inequity in Virginia Law. Restorative justice is also necessary for formerly convicted people, including the removal of barriers to housing, employment, and voting.

Stories

Dig deeper into the topics by exploring the stories of the past that have shaped the present.

Desegregation of Stratford Junior High and the End of Virginia’s Massive Resistance

On the morning of February 2, 1959, Ronald Deskins, a 12-year old boy in Arlington, was very nervous about his first day of school. While

E.B. Henderson

Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson spent most of his childhood living in an integrated neighborhood in Washington D.C. But during the summer, he stayed with his

The Syphax Family

When he was young, Stephen Hammond did not believe he was related to the family of George and Martha Washington. But when Hammond traced his

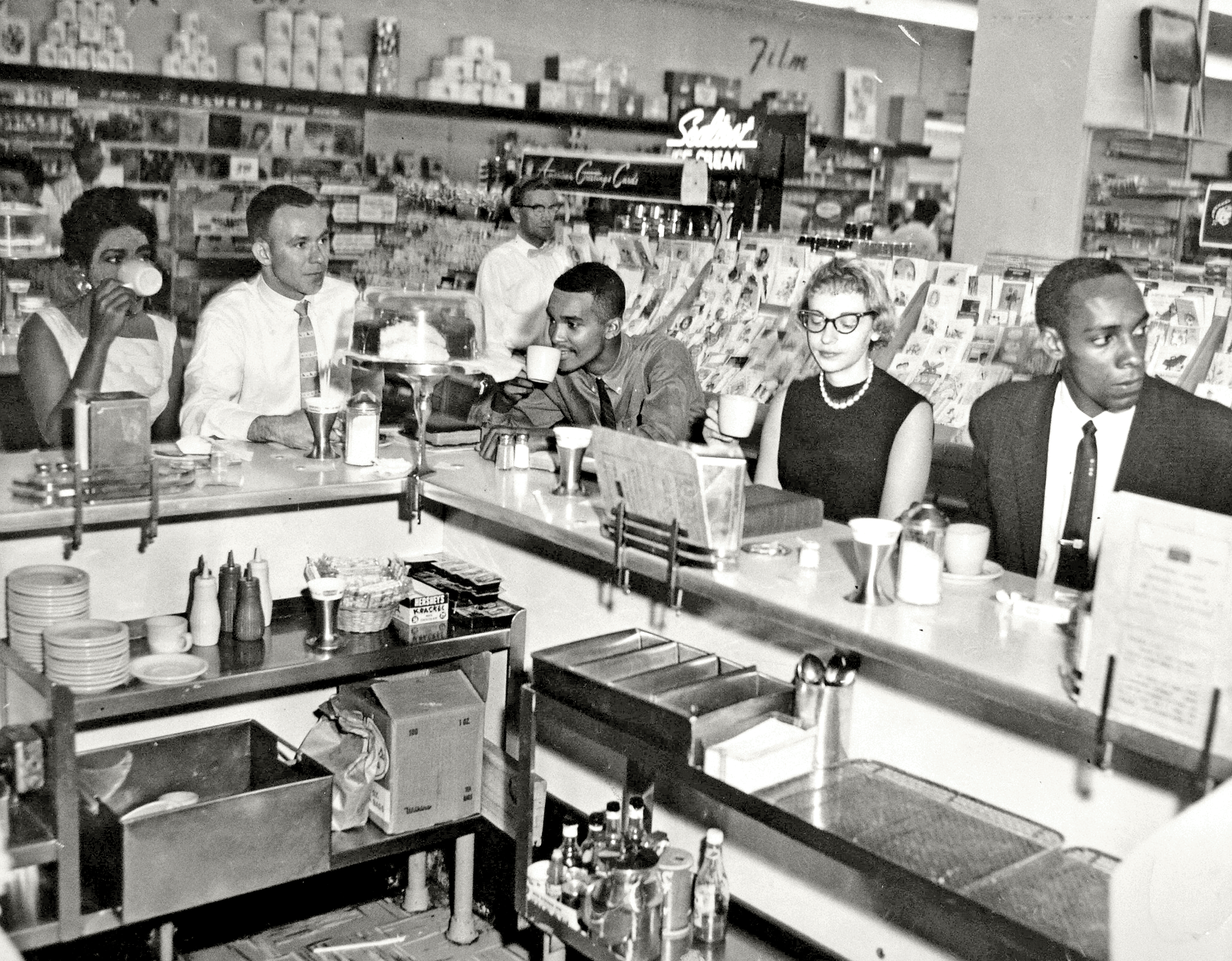

Dion Diamond: Doing What is Right

Dion Diamond was always a prankster. He used this fearlessness and humor to, as he put it, “crash segregated society.” A 1960 photo shows him

The Quest for Education

On cold winter days, Minnie Hughes, a school teacher at the Fairfax Colored School, would heatup a kettle and pour the water onto the hands